![]()

[ PART ONE ]

The Bible as History?

![]()

[ 1 ]

Searching for the Patriarchs

In the beginning was a single family, with a special relationship to God. In time, that family was fruitful and multiplied greatly, growing into the people of Israel. That is the first great saga of the Bible, a tale of immigrant dreams and divine promises that serves as a colorful and inspiring overture to the subsequent history of the nation of Israel. Abraham was the first of the patriarchs and the recipient of a divine promise of land and plentiful descendants that was carried forward across the generations by his son Isaac, and Isaac’s son Jacob, also known as Israel. Among Jacob’s twelve sons, each of whom would become the patriarch of a tribe of Israel, Judah is given the special honor of ruling them all.

The biblical account of the life of the patriarchs is a brilliant story of both family and nation. It derives its emotional power from being the record of the profound human struggles of fathers, mothers, husbands, wives, daughters, and sons. In some ways it is a typical family story, with all its joy and sadness, love and hatred, deceit and cunning, famine and prosperity. It is also a universal, philosophical story about the relationship between God and humanity; about devotion and obedience; about right and wrong; about faith, piety, and immorality. It is the story of God choosing a nation; of God’s eternal promise of land, prosperity, and growth.

From almost every standpoint—historical, psychological, spiritual—the patriarchal narratives are powerful literary achievements. But are they reliable annals of the birth of the people of Israel? Is there any evidence that patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—and matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel—actually lived?

A Saga of Four Generations

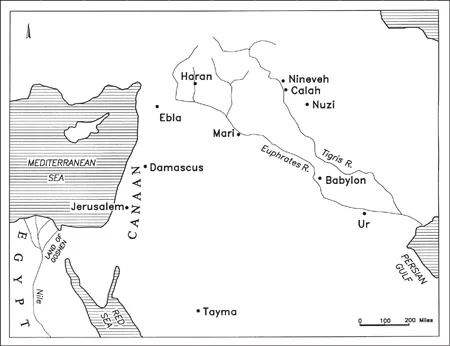

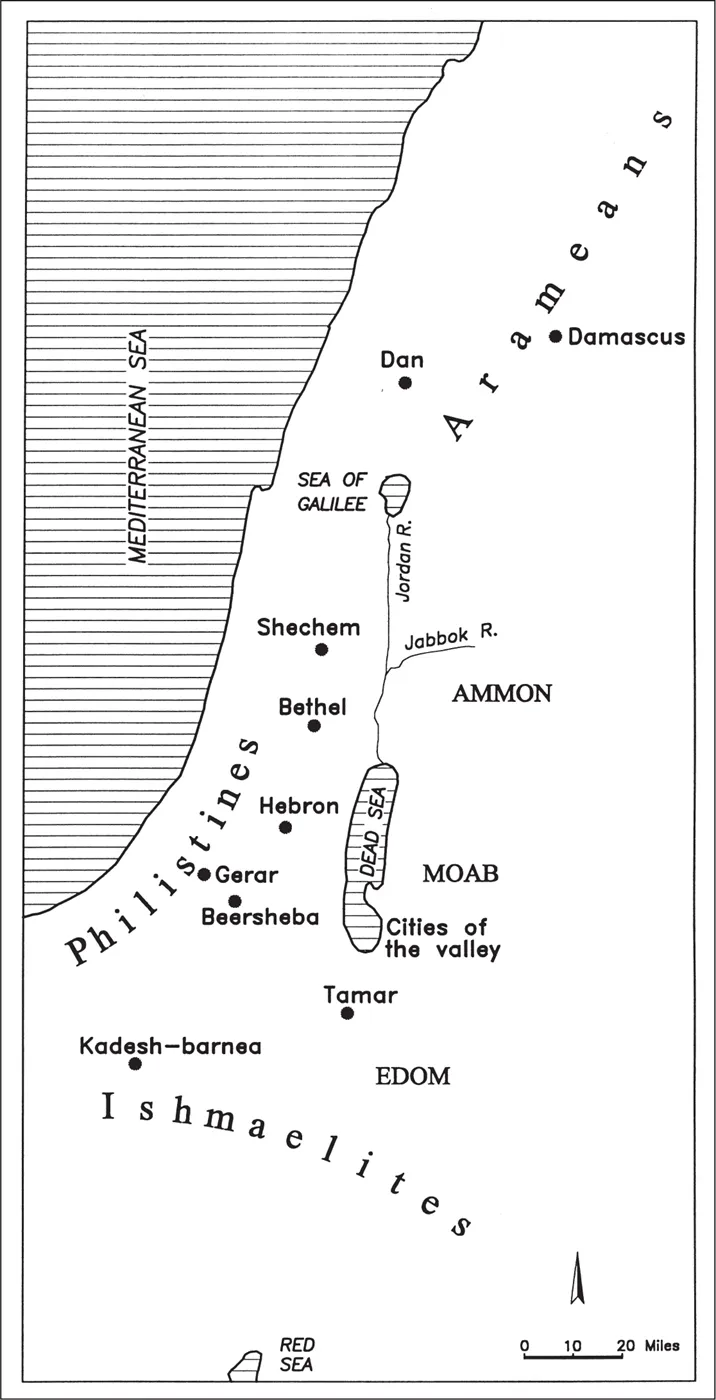

The book of Genesis describes Abraham as the archetypal man of faith and family patriarch, originally coming from Ur in southern Mesopotamia and resettling with his family in the town of Haran, on one of the tributaries of the upper Euphrates (Figure 4). It is there that God appeared to him and commanded him, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great so that you will be a blessing” (Genesis 12: 1–2). Obeying God’s words, Abram (as he was then called) took his wife, Sarai, and his nephew Lot, and departed for Canaan. He wandered with his flocks among the central hill country, moving mainly between Shechem in the north, Bethel (near Jerusalem), and Hebron in the south, but also moving into the Negev, farther south (Figure 5).

During his travels, Abram built altars to God in several places and gradually discovered the true nature of his destiny. God promised Abram and his descendants all the lands from “the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates” (Genesis 15:18). And to signify his role as the patriarch of many people, God changed Abram’s name to Abraham—“for I have made you the father of a multitude of nations” (Genesis 17:5). He also changed his wife Sarai’s name to Sarah to signify that her status had changed as well.

The family of Abraham was the source of all the nations of the region. During the course of their wandering in Canaan, the shepherds of Abraham and the shepherds of Lot began to quarrel. In order to avoid further family conflict, Abraham and Lot decided to partition the land. Abraham and his people remained in the western highlands while Lot and his family went eastward to the Jordan valley and settled in Sodom near the Dead Sea. The people of Sodom and the nearby city of Gomorrah proved to be wicked and treacherous, but God rained brimstone and fire on the sinful cities, utterly destroying them. Lot then went off on his own to the eastern hills to become the ancestor of the Transjordanian peoples of Moab and Ammon. Abraham also became the father of several other ancient peoples. Since his wife, Sarah, at her advanced age of ninety, could not produce children, Abraham took as his concubine Hagar, Sarah’s Egyptian slave. Together they had a child named Ishmael, who would in time become the ancestor of all the Arab peoples of the southern wilderness.

Figure 4: Mesopotamian and other ancient Near Eastern sites connected with the patriarchal narratives.

Most important of all for the biblical narrative, God promised Abraham another child, and his beloved wife, Sarah, miraculously gave birth to a son, Isaac, when Abraham was a hundred years old. One of the most powerful images in the Bible occurs when God confronts Abraham with the ultimate test of his faith, commanding him to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac on a mountain in the land of Moriah. God halted the sacrifice but rewarded Abraham’s display of faithfulness by renewing his covenant. Not only would Abraham’s descendants grow into a great nation—as numerous as the stars in the heavens and the sand on the seashore—but in the future all the nations of the world would bless themselves by them.

Isaac grew to maturity and wandered with his own flocks near the southern city of Beersheba, eventually marrying Rebecca, a young woman brought from his father’s homeland far to the north. In the meantime, the family’s roots in the land of the promise were growing deeper. Abraham purchased the Machpelah cave in Hebron in the southern hill country for burying his beloved wife, Sarah. He would also later be buried there.

The generations continued. In their encampment in the Negev, Isaac’s wife, Rebecca, gave birth to twins of completely different characters and temperaments, whose own descendants would carry on a struggle between them for hundreds of years. Esau, a mighty hunter, was the elder and Isaac’s favorite, while Jacob, the younger, more delicate and sensitive, was his mother’s beloved child. And even though Esau was the elder, and the legitimate heir to the divine promise, Rebecca disguised her son Jacob with a cloak of rough goatskin. She presented him at the bed of the dying Isaac so that the blind and feeble patriarch would mistake Jacob for Esau and unwittingly grant him the birthright blessing due to the elder son.

On returning to the camp, Esau discovered the ruse—and the stolen blessing. But nothing could be done. His aged father, Isaac, promised Esau only that he would become the father of the desert-dwelling Edomites: “Behold, away from the fatness of the earth your dwelling shall be” (Genesis 27:39). Thus another of the peoples of the region was established and in time, as Genesis 28:9 reveals, Esau would take a wife from the family of his uncle Ishmael and beget yet other desert tribes. And these tribes would always be in conflict with the Israelites—namely, the descendants of his brother, Jacob, who snatched the divine birthright from him.

Jacob soon fled from the wrath of his aggrieved brother and journeyed far to the north to the house of his uncle Laban in Haran, to find a wife for himself. On his way north God confirmed Jacob’s inheritance. At Bethel Jacob stopped for a night’s rest and dreamed of a ladder set up on the earth, with its top reaching heaven and angels of God going up and down. Standing above the ladder, God renewed the promise he had given Abraham:

I am the LORD, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants; and your descendants shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and by you and your descendants shall all the families of the earth bless themselves. Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done that of which I have spoken to you. (GENESIS 28:13–15)

Jacob continued northward to Haran and stayed with Laban several years, marrying his two daughters, Leah and Rachel, and fathering eleven sons—Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, and Joseph—from his two wives and from their two maidservants. God then commanded Jacob to return to Canaan with his family. Yet on his way, while crossing the river Jabbok in Transjordan, he was forced to wrestle with a mysterious figure. Whether it was an angel or God, the mysterious figure changed Jacob’s name to Israel (literally, “He who struggled with God”), “for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed” (Genesis 32:28). Jacob then returned to Canaan, setting up an encampment near Shechem and building an altar at Bethel—in the same place where God had revealed himself to him on his way to Haran. As they moved farther south, Rachel died in childbirth near Bethlehem as she gave birth to Benjamin, the last of Jacob’s sons. Soon afterward Jacob’s father, Isaac, died and was buried in the cave of Machpelah in Hebron.

Slowly the family was becoming a clan on the way to becoming a nation. Yet the children of Israel were at this stage still a family of squabbling brothers, among whom Joseph, Jacob’s favored son, was detested by all the others because of his bizarre dreams that predicted he would reign over his family. Though most of the brothers wanted to murder him, Reuben and Judah dissuaded them. Instead of slaying Joseph, the brothers sold him to a group of Ishmaelite merchants going down to Egypt with a caravan of camels. The brothers feigned sadness and explained to the patriarch Jacob that a wild beast had devoured Joseph. Jacob mourned his beloved son.

But Joseph’s great destiny would not be averted by his brothers’ jealousy. Settling in Egypt, he rose quickly in wealth and status because of his extraordinary abilities. After interpreting a dream of the pharaoh predicting seven good years followed by seven bad years, he was appointed the pharaoh’s grand vizier. In that high position he reorganized the economy of Egypt by storing surplus food from good years for future bad years. Indeed, when the bad years finally commenced, Egypt was well prepared. In nearby Canaan, Jacob and his sons suffered from famine and Jacob sent ten of his eleven remaining sons to Egypt for food. In Egypt, they went to see the vizier Joseph—now grown to adulthood. Jacob’s sons did not recognize their long-lost brother and Joseph did not initially reveal his identity to them. Then, in a moving scene, Joseph revealed to them that he was the scorned brother whom they sold away into slavery.

![]()

Figure 5: Main places and peoples in Canaan mentioned in the Patriarchal narratives.

![]()

The children of Israel were at last reunited, and the aged patriarch Jacob came to live with his entire family near his great son, in the land of Goshen. On his deathbed, Jacob blessed his sons and his two grandsons, Joseph’s sons Manasseh and Ephraim. Of all the honors, Judah received the royal birthright:

Judah, your brothers shall praise you; your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies; your father’s sons shall bow down before you. Judah is a lion’s whelp; from the prey, my son, you have gone up. He stooped down, he couched as a lion, and as a lioness; who dares rouse him up? The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until he comes to whom it belongs; and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples. (GENESIS 49:8–10)

And after the death of Jacob, his body was taken back to Canaan—to the territory that would someday become Judah’s tribal inheritance—and was buried by his sons in the cave of Machpelah in Hebron. Joseph died too, and the children of Israel remained in Egypt where the next chapter of their history as a nation would unfold.

The Failed Search for the Historical Abraham

Before we describe the likely time and historical circumstances in which the Bible’s patriarchal narrative was initially woven together from earlier sources, it is important to explain why so many scholars over the last hundred years have been convinced that the patriarchal narratives were at least in outline historically true. The pastoral lifestyle of the patriarchs seemed to mesh well in very general terms with what early twentieth century archaeologists observed of contemporary bedouin life in the Middle East. The scholarly idea that the bedouin way of life was essentially unchanged over millennia lent an air of verisimilitude to the biblical tales of wealth measured in sheep and goats (Genesis 30:30–43), clan conflicts with settled villagers over watering wells (Genesis 21:25–33), and disputes over grazing lands (Genesis 13:5–12). In addition, the conspicuous references to Mesopotamian and Syrian sites like Abraham’s birthplace, Ur, and Haran on a tributary of the Euphrates (where most of Abraham’s family continued to live after his migration to Canaan) seemed to correspond with the findings of archaeological excavations in the eastern arc of the Fertile Crescent, where some of the earliest centers of ancient Near Eastern civilization had been found.

Yet there was something much deeper, much more intimately connected with modern religious belief, that motivated the scholarly search for the “historical” patriarchs. Many of the early biblical archaeologists had been trained as clerics or theologians. They were persuaded by their faith that God’s promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the birthright of the Jewish people and the birthright passed on to Christians, as the apostle Paul explained in his letter to the Galatians—was real. And if it was real, it was presumably given to real people, not imaginary creations of some anonymous ancient scribe’s pen.

The French Dominican biblical scholar and archaeologist Roland de Vaux noted, for example, that “if the historical faith of Israel is not founded in history, such faith is erroneous, and therefore, our faith is also.” And the doyen of American biblical archaeology, William F. Albright, echoed the sentiment, insisting that “as a whole, the picture in Genesis is historical, and there is no reason to doubt the general accuracy of the biographical details.” Indeed, from the early decades of the twentieth century, with the great discoveries in Mesopotamia and the intensification of archaeological activity in Palestine, many biblical historians and archaeologists were convinced that new discoveries could make it likely—if not completely prove—that the patriarchs were historical figures. They argued that the biblical narratives, even if compiled at a relatively late date such as the period of the united monarchy, preserved at least the main outlines of an authentic, ancient historical reality.

Indeed, the Bible provided a great deal of specific chronological information that might help, first of all, pinpoint exactly when the patriarchs lived. The Bible narrates the earliest history of Israel in sequential order, from the patriarchs to Egypt, to Exodus, to the wandering in the desert, to the conquest of Canaan, to the period of the judges, and to the establishment of the monarchy. It also provided a key to calculating specific dates. The most important clue is the note in 1 Kings 6:1 that the Exodus took place four-hundred eighty years before the construction of the Temple began in Jerusalem, in the fourth year of the reign of Solomon. Furthermore, Exodus 12:40 states that the Israelites endured four-hundred thirty years of slavery in Egypt before the Exodus. Adding a bit over two hundred years for the overlapping life spans of the patriarchs in Canaan before the Israelites left for Egypt, we arrive at a biblical date of around 2100 BCE for Abraham’s original departure for Canaan.

Of course, there were some clear problems with accepting this dating for precise historical reconstruction, not the least of which were the extraordinarily long life spans of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, which all far exceeded a hundred years. In addition, the later genealogies that tr...