eBook - ePub

Strategic Supremacy

How Industry Leaders Create Spheres of Influence from Their Product Portfolios to Achieve Preeminence

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Supremacy

How Industry Leaders Create Spheres of Influence from Their Product Portfolios to Achieve Preeminence

About this book

Are upstart competitors taking deadly aim at your company's products and markets? Richard A. D'Aveni, author of the famous attacker's handbook Hypercompetition, presents coun-terrevolutionary strategies and tactics that any industry leader or established company can use to defend itself against revolutionaries, disrupters, or hypercompetitors. The secret lies in making the rules, not breaking them, D'Aveni says, because rule makers still rule. Arguing that "profits and prosperity come not from revolution but stability and orderly change," D'Aveni presents a commanding framework that will enable any resource-rich or clever defender to gain Strategic Supremacy by being first to define the playing field.

D'Aveni demonstrates how global powerhouses such as Disney, Microsoft, and Procter & Gamble have achieved preeminence by reconceptualizing their product portfolios as powerful competitive arsenals he calls "spheres of influence." Essentially a new way to compete by restructuring portfolios around a core geographic/product market, spheres enable any company to influence the behavior and positioning of rivals. In immensely readable prose, D'Aveni describes how prevailing spheres of influence can be used to create legal business equivalents to a "concert of powers" and other industry structures that mix cooperation with competition. Just one of the potent functions of a corporate sphere, D'Aveni shows, is to contain competitors of equal size (as NBC contained ABC). Spheres can also be used to stabilize an entire industry's global power system.

A glance at the detailed table of contents will provide a sense of the wealth of new information contained in this essential handbook of global warfare, including "how-to" tools the reader will need to measure and map the pattern of competitive pressure in any industry and to interpret the meaning and strategic implications of these pressure patterns for his or her position within the industry's power hierarchy.

D'Aveni demonstrates how global powerhouses such as Disney, Microsoft, and Procter & Gamble have achieved preeminence by reconceptualizing their product portfolios as powerful competitive arsenals he calls "spheres of influence." Essentially a new way to compete by restructuring portfolios around a core geographic/product market, spheres enable any company to influence the behavior and positioning of rivals. In immensely readable prose, D'Aveni describes how prevailing spheres of influence can be used to create legal business equivalents to a "concert of powers" and other industry structures that mix cooperation with competition. Just one of the potent functions of a corporate sphere, D'Aveni shows, is to contain competitors of equal size (as NBC contained ABC). Spheres can also be used to stabilize an entire industry's global power system.

A glance at the detailed table of contents will provide a sense of the wealth of new information contained in this essential handbook of global warfare, including "how-to" tools the reader will need to measure and map the pattern of competitive pressure in any industry and to interpret the meaning and strategic implications of these pressure patterns for his or her position within the industry's power hierarchy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strategic Supremacy by Richard A. D'aveni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Sphere of Influence

Rethinking Your Product Portfolio to

Achieve Strategic Supremacy

OVERVIEW

For firms in dynamic industries, traditional portfolio models that focus primarily on core competencies and synergies can be dangerously shortsighted. Great powers throughout political and business history have demonstrated that a far more effective means of achieving growth, wealth, and power is to frame your organization as a cohesive sphere of influence. The sphere is your competitive arsenal, serving as your offensive, defensive, and reserve artillery. It not only consists of your core geo-product markets and vital interests, but also buffer zones, pivotal zones, and forward positions, each serving a specific strategic intent. From its center to its far-flung borders, a cohesive sphere of influence gives your organization the power and the critical ammunition to achieve and sustain strategic supremacy.

VENI, VIDI, VICI

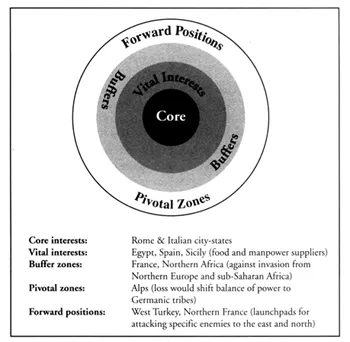

The Roman Empire rose to power out of the chaos of the declining Etruscan Empire. This power vacuum allowed Rome to establish its own supremacy within the Italian peninsula, using other Italian city-states as buffers against rival powerful empires centered in Carthage and Greece.

With Italy as a secure base, Rome gradually expanded its sphere of influence far beyond the aspirations of the Etruscans. During its early growth period from approximately the sixth to the second century B.C., Rome captured Spain and created forward positions in Sicily, where it faced both Carthage and Greece. It skillfully defeated Carthage completely before turning to the domination of Greece, avoiding overstretching its resources by fighting on only one front at a time.

As Rome continued to expand to the height of its empire (from approximately the first century B.C. to the end of the second century A.D.) it established extensive buffer zones, vital interests, and forward positions reaching to Northern France and Southern England. Each conquest satisfied a particular strategic need of the empire. Some territories were acquired because they were targets of opportunity, resulting from power vacuums. Others satisfied Rome’s need for buffers against competing empires in the Middle East or powerful Germanic tribes to the north. Still others provided vital supplies, such as food, soldiers, metals, or trade goods. Much of Rome’s growth was obtained by force (after all, Rome was a warrior nation). But as the empire grew in scope, the Roman ideology—embodied in its citizenship and system of governance—played a role just as important as its legionnaires in controlling its vast empire (see Exhibit 1-1).

At the death of Augustus in A.D. 14, Rome was the largest political, economic, and monetary entity to exist in the western world until it was overtaken by the expansion of the United States and the Russian Empire in the mid nineteenth century. Moreover, Rome spread its wealth fairly well for its time, with the Roman distribution of income in A.D. 14 looking approximately the same as in England in the early nineteenth century1 While some may view the story of the Roman Empire as ancient history, many of today’s most successful modern global businesses have used similar strategies to achieve strategic supremacy.

Like Rome, industry leaders have achieved strategic supremacy—the power to conquer chaos and to fashion a favorable world by shaping the playing field. Rome did so by defining its territorial borders, the borders of its rivals’ territories, and even the boundaries of the “civilized” world. Like Rome, these companies have built their strategic supremacy in physical space and cyberspace by identifying a center of interest or core market and then staking out different interests around that core—vital interests, buffer zones, pivotal zones, and forward positions. By building a cohesive sphere of influence, these great powers clarify their corporate-wide strategy, specifying their strategic interests in each part of their portfolios and assigning a clear role for each of those parts in competing with rivals.

Exhibit 1-1: The Roman Sphere of Influence at Its Height-133 B. C.-A.D. 200

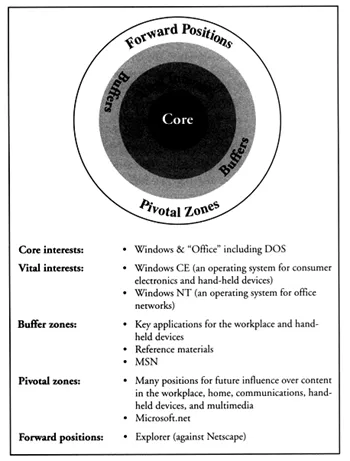

Microsoft is but one example of a modern firm that parallels Ancient Rome’s development and use of a sphere of influence. While Rome’s sphere was built around a capital city, Microsoft’s sphere was built around a core market—the desktop operating system and graphical user interface. The company created its own software applications to buffer its core against potential invasion by application software providers. Microsoft also built its portal website, Microsoft Network (MSN), to buffer itself against attacks by AOL, Yahoo!, and other portals. Microsoft used Internet Explorer as a forward position against Netscape, bundling it for free with Windows in an attempt that appeared so imperial that the Justice Department found it to be “anti-competitive.” Microsoft has also built vital interests in the critical networking and personal digital assistant software markets using Windows NT and CE. These positions were designed to capture growth markets vital to setting the standards for operating systems in the personal computing world (see Exhibit 1-2).

More recently, even as Microsoft contends with the aftermath of the government’s antitrust case against it, Bill Gates and his legions are working hard to regroup and regenerate Microsoft’s sphere of influence. Just as the Roman Empire regrouped and regenerated its sphere through migrating its core to Constantinople, Microsoft is migrating its core from desktop operating systems and graphical user interfaces to an integrated desktop-Internet operating system and interface. This would allow users to access desktop applications and Web content or applications seamlessly and to exchange data between the desktop’s hard drive and Web sites with greater ease and speed. Rome’s migration helped it to sustain its power longer than any other political empire in history Many think that Microsoft’s migration will do the same for Bill Gates because they believe Microsoft is creating the next “Windows” on the Web. In addition, during 2001, the company is increasing its presence on the Web, converting MSN from a buffer to a “pivotal” zone. Microsoft is beginning an MSN growth campaign to counter the rise of new threatening great powers such as the Godzilla that resulted from the merger of AOL and Time Warner (especially in light of the fact that AOL has already swallowed Microsoft rival Netscape).

Despite 2,000 years separating Microsoft and Ancient Rome, the sphere of influence concept offers a critical common framework for understanding how both these great powers have achieved strategic supremacy. The world may look different today, but the sphere of influence as a framework has stood the test of time. Companies and businesses that become great powers, that achieve strategic supremacy, do so by shaping a coherent sphere of influence. In essence, the sphere is a competitive arsenal, with different zones of the sphere serving as offensive, defensive, or reserve artillery for the future. In business as in politics, some zones in the sphere are wholly owned and contribute directly to its financial coffers. Other zones may not be directly owned or contribute directly to economic success of the core; nevertheless they play an important strategic role.

Exhibit 1-2: Microsoft’s Sphere of Influence—1997-2000

A great power’s sphere is more than a portfolio with synergies. It is a gestalt of powerful proportions because a great power’s sphere of influence is much greater than the sum of its parts when the sphere is cohesive. Every zone of a sphere that surrounds its core—from its buffers to its far-flung territories—must contribute to the overall strength of the sphere, even if the zone has no direct synergies with the core. Indeed, in political empires throughout history, and in industries from computer chips to corn chips, the player that enjoys strategic supremacy or preeminence in the competitive space has been the company with the strongest, most cohesive sphere of influence.

LOOKING BEYOND TRADITIONAL PORTFOLIOS

TO SPHERES OF INFLUENCE

The sphere of influence concept offers a richer framework for building growth, wealth, and power than traditional portfolio models. Traditional frameworks for developing a corporation’s portfolio of businesses typically define a good portfolio as a collection of related businesses or solid niches in several geo-product markets, primarily designed to achieve synergies among the portfolio’s businesses. Synergies come from leveraging core competencies and selecting new markets that are related to your core market.

However, when managers create this type of portfolio, they do not necessarily establish a powerful presence in the larger competitive space, and they tend to overlook significant opportunities (and threats) to the company’s strategic interests that lie beyond the parameters of the portfolio. For example, managers may overlook threats posed by competing portfolios or growth opportunities that don’t appear to be immediately related to the company’s businesses. Would a synergy-based portfolio approach have seen the opportunity for Morton to shift its core from the low-profit salt market to the high-margin rocket market (which Morton has done successfully)? Or would it have prevented Penn Central’s powerful railroad portfolio from meeting an untimely demise? Did Kodak’s strategy of sticking to its core competence in photochemical photography prepare it for the threats of the digital age? Seemingly remote threats and opportunities can actually tip the balance of power away from your company to a competitor that has built a strong sphere of influence.

Related diversification appears to avoid some of the drawbacks of unrelated business groups, but the research is inconclusive. For example, a global study of more than eight hundred business groups spanning fourteen countries found affiliates of these highly diversified groups had higher returns than their peers in several countries.2 The study’s findings run contrary to the traditional American wisdom that unrelated diversification depresses profitability, and that unrelated business groups are only useful in countries with inefficient financial markets.

Corporate history is also far from clear on this point. Coca-Cola has created a lasting billion-dollar empire around a single core. But Motorola stuck close to its core in analog cellular phones and infrastructure and, yet, lost the leadership of its market. Motorola found that it made a lot of money for a while but, over the long run, this core-competence-based portfolio milked the company’s present resources at the expense of the future. Perhaps the best example of a firm that violates traditional American wisdom concerning relatedness, synergies, and leveraging core competencies is General Electric. It has been one of the biggest wealth creators in the stock market over a period of more than one hundred years. Yet, GE’s portfolio—an empire ranging from light bulbs to financial services—is thriving.

Why are the senior managers of so many industry leading firms diversifying their portfolios in ways that buck conventional wisdom? Where are the synergies in many of the global mega-mergers we see today? Is there any valid strategic reason that justifies why Daimler-Benz and Chrysler merged, given the difficulty of combining their vastly different corporate cultures and the contradictions created by putting the Mercedes brand name under the same roof as the Neon? Can Citicorp really take advantage of synergies between Citibank, Traveler’s Insurance, and Salomon Smith Barney?

In most cases, large firms cannot capture synergies. Their internal cultural differences are too great, and the costs of coordinating diverse and dispersed subunits are too high. So, are the senior managers of these diversifying firms simply crazy egomaniacs on a lucky streak? Or have they tapped into some greater strategic purpose for their diverse interests—one that goes beyond related or unrelated diversification—as a framework for shaping their companies’ global position relative to other global players?

There is obviously much more at play here than the relatedness of the elements of the portfolio. It is equally, if not more, important to consider how the elements of a portfolio are going to be used competitively Of course these elements must be used to create wealth in the near term—making the profit-enhancing benefits of synergies, core competencies, and relatedness with your core markets important. But the elements of the portfolio can also be used to serve long-term purposes. For example, parts of your portfolio can be used for maneuvering against competitors to stake out a superior position in your competitive space, and to signal others about which parts of the space they should occupy. Other parts of your portfolio can be used to enter markets unrelated to your core, but which match important trends or which may become safehavens beyond the reach of aggressive competitors. These often ignored, larger competitive purposes of a portfolio are the focus of the sphere of influence concept.

The sphere of influence concept helps you examine the roles of each part of your sphere of influence and how these different parts interact. There are different defensive and offensive roles for each part of your portfolio that have to be considered. Because your environment is constantly being shaped by your customers and by your competitors, your portfolio is in dynamic motion. Traditional portfolio models can be too static or focus too closely on the present, hence risking your future strategic supremacy. They can also narrow your perspective too much, underutilizing your company as a platform for growth and for building the power you will need to survive the many struggles you will have with other global giants.

When facing off against global corporations with massive power, the key to success is to think of your portfolio as a sphere of influence, in which each piece serves as a source for your power. A diversified company’s power must start from a secure core and synergies around it. But its presence in other zones can serve to enhance its power by projecting its sphere into unoccupied geo-product markets that threaten a competitor. In addition, its presence in other zones can position the sphere to defend itself against rivals seeking to build platforms for invasion.

Rather than the issue of relatedness, spherical growth focuses on more meaningful issues: How can you protect your present turf? How can you absorb new wealth and power while expending fewer resources than you gain? How can you avoid contact with more powerful players as you fortify and expand your own sphere? How and where must your sphere interact with rivals in order to achieve your ambitions or thwart another’s drive for supremacy? And where should you position your sphere for the future in the event of a seismic shift in your industry?

By shifting from synergistic portfolio models to the richer sphere of influence framework, your company can enjoy a much broader and more insightful view of the competitive playing field. Quickly it becomes much clearer what areas—both inside and outside your company’s holdings—can contribute to your wealth, power, and growth.

In the sphere of influence framework, your company does not have a single strategic intent. Your portfolio is actually revealed as a portfolio of many intentions that make up a cohesiv...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE: The Art of Strategy

- INTRODUCTION: Strategic Supremacy

- Chapter 1: The Sphere of InfluenceRethinking Your Product Portfolio toAchieve Strategic Supremacy

- Chapter 2: Leading the EvolutionCircumventing Competitive Compression to Grow the Power of Your Sphere

- Chapter 3: Paradigms for PowerRouting Your Resources to Unleash the Potential of Your Sphere

- Chapter 4: Dousing DisruptionUsing Counterrevolutionary Tactics Weatherproofing Strategies and Competitive Cooperatives to Manage Insurrection

- Chapter 5: Competitive ConfigurationShaping Great Power Relationships to Gain Preeminence for Your World View

- Chapter 6: Global Power SystemsIntervening in Your Industry to Stabilize or Transform the Distribution of Power

- APPENDICES Appendix A

- APPENDIX B

- NOTES

- INDEX