![]()

SPRING

All those who are in Rome / to harm our nation’s home

To plot against our Duce / who guides our Fascist future

Must first confront a band / under Pietro Koch’s command

It’s he who lays the brilliant plans … / by which we nab the Partisans

Then they face interrogation / unlucky them, a hopeless situation …

From the room next door you can hear the sound / of how the pleasures of the prisoner abound

If he persists and there‘s nothing he’ll reveal / there’s our man Zangheri who’ll make him squeal

But just what are those cries of pain? / The work of Billi, going at it again?

Or do they come from the mighty fists / of big Pallone’s massive mitts? …

And though the Communist’s face grows sadder / in the end he tells all just to end the matter …

So this is Koch’s squad / men strong-minded and hard

Who work for Italy’s glory / and for our Fascist victory

And I, who have come to know you / shout “Onward Duce!” as heartily as you do

“Marcella” [1944] [“Hymn” of the Koch Gang; cf. Griner: 33-37]

The sun heavy with cruel light

rays embedded in the red haze of spring

Men passed like shadows on the lines of ashes and asphaltfaces that do not cling to memory …

Under the pounding heels

a cadence resounded on the pavement

echoing in the heart

(Only the brain left the vow intact)

At a nod from Cola it was understood

that the moment of judgment had arrived

Eyes upon us at every corner

watching, waiting

and it passed, swept away with fear

the timidity of youth

of our twenty years

Carla Capponi, “Elena” 1944 [DIR: 71]

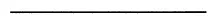

![]()

THIRTEEN

VIA RASELLA

WHEN Giovanni returned with Maria to the cellar hideout, they told Paolo and Elena about the column of SS troops marching so brazenly through Rome. The four Partisans began to follow arid clock the marchers. After the column reached the top of the Via Rasella, it turned right at the corner, onto the main thoroughfare Via Quattro Fontane and marched a final, straight line of about a third of a mile to the Interior Ministry and their barracks. The corner formed a suitable blind for an urban ambush from which the Partisans could launch several hand grenades as the column turned; then they could escape in the confusion. This “bite-and-run” tactic had become a staple by now, a reliable formula for a high rate of success, but when the four proposed it to Spartaco, he viewed it as requiring a brand-new approach. A bite-and-run strike on such a large target seemed wasted, less than a glancing blow. Here was the Via Rasella, a narrow passage between two wide streets, near the end of a long march, a tiring hill to climb and a configuration that compacted the target and reduced its room for maneuver. It was the only street on the 11th Company’s route where an attack seemed feasible. The whole bellowing Bozen SS company would be funneling into a trap. Although none of the attacks in Rome thus far had employed more than three or four Partisans, Spartaco said he would make four squads of GAP Central available, some sixteen men and women, if they could be used efficiently.1

Thinking big was in the spring air. An even larger-scale operation was already scheduled to take place on March 23. It would combine forces of GAP Central and the Socialists’ Matteotti Brigade—named for the Socialist leader who had stood between Mussolini and dictatorial power until he was murdered. The joint attack would be an unprecedented act tantamount to sacking the Fascist pantheon. On the calendar of the so-called Era Fascista, March 23 of every year was a red-letter day. It was on that day in 1919 that young Mussolini and 144 other disgruntled but kindred souls founded the Fascist movement in a meeting hall in Milan’s Piazza San Sepolcro.

Thus March 23 would be the twenty-fifth anniversary of that historic day, an anniversary to be celebrated by the Fascists in occupied Rome. Such was the ardor, in fact, that party Vice Secretary Giuseppe Pizzirani was convinced that Mälzer’s ban on public manifestations of Fascist pride could not possibly stand in the way of his plans for a gala commemoration. He foresaw a daylong series of events all over Rome. A morning church service to honor Fascism’s fallen heroes, an afternoon parade of Fascism’s many varieties of flags, pennants, and buntings, culminating in a rousing assembly at Fascism’s traditional auditorium, the Teatro Adriano.2

The announcement of all this and more in the press, on the radio, and on the walls of Rome on the first day of spring provided the final details needed for the Partisan attack, already well along in the planning. The Military Council had been preparing at least as actively as Pizzirani to mark this special anniversary. An electrifying demonstration of the might and presence of the Resistance on Fascism’s most sacred day could not but be a tonic for the sorely tried people of Rome. The Matteotti Brigade would attack the Fascist parade and the Gappisti would follow with a major assault at the Teatro Adriano.3

Pizzirani’s plans, however, had also attracted Consul Möllhausen. In the months since his “liquidate” reprimand, he had recovered lost ground by not using the word again and keeping a low profile. But there was something about the idea of Fascists celebrating anything that was grating to the sensibilities of all the occupiers. “A display of Fascist pomp and ceremony on that day,” the diplomat said later, “while the people of Rome were going hungry and saw Fascism as the cause of their suffering, seemed inopportune.” He decided to call a meeting at the Villa Wolkonsky to discuss the matter with Dollmann, Kappler, and Mälzer. They need not have gone to the trouble of attending, since none of them, Möllhausen knew, would have a kind word to say about the Fascists, but the fireplace in the embassy’s Red-and-White Room, the ritual passing around of cigars and the prewar cognac poured by men in white gloves were reasons enough to gather.

Möllhausen introduced his guests to his opinion that “to parade through the city to the sound of Fascist music and the sight of Fascist banners was nothing but a useless provocation.” Dollmann agreed. He wanted the ceremonies shortened. Kappler said that politics was not his field, “but if I were asked I would say that neofascism has to disappear so that we can hold onto the last vestige of German prestige in Italy. This requires the elimination of Mussolini, and if I were charged with that task, I would know just how to carry it out.” The only surprise came from Mälzer, who said he was not at liberty to ban the ceremonies. He had received word from Berlin that the Führer, aware of the rampant low regard for his ally, was insisting that the Fascists be treated as “authentic friends.” The same source in Berlin, however, left the matter to Mälzer’s decision. Mälzer canceled the parade, shifted the Teatro Adriano assembly to the heavily guarded Ministry of Corporations on the Via Veneto, and gave Pizzirani permission to hold the church service as planned. Pizzirani was incensed. He protested to Mälzer, then to the Duce himself, but got nowhere.4

When word of the cancellation of the parade and the Teatro Adriano event reached the Military Council, it had to make a swift change of plans. A new counterdemonstration was approved, scheduled to take place on March 23. While the Fascists would celebrate in the Via Veneto, the Gappisti, proceeding from a newly elaborated plan, would launch their attack in Via Rasella.

THE LEADERS of all three political parties who ran the Military Council were in agreement that the main objective of the operation in the Via Rasella, apart from injuring the occupation forces, was to provide a galvanizing show of strength against the common enemy. But the Roman resistance was never more divided than on the eve of its largest endeavor. That night of the 22nd, CLN President Bonomi, hiding in his nephew’s apartment in the Trionfale district, had been brought a message from one of the six member parties, which seemed to him to signal the imminent collapse of the coalition. The issue, as had become usual, was the price that the King and Badoglio would have to pay for having abandoned Rome.

Continually inflamed by Churchill’s support for the monarchy, against sharp disagreement from Roosevelt, the matter had flared up again in recent days in a surprise move by Stalin. Apparently believing he was somehow blocking a nefarious design of British and American imperialists, he granted diplomatic recognition of the Badoglio government, strengthening the King perhaps but weakening the CLN. Shortly afterward CLN leaders met to shore up their elusive unity in a resolution that would have removed the monarchy question until after Rome’s liberation from Nazi rule.

While the capital shook under one of the heaviest Allied bombings, the measure was put to a vote. It drew approval from five of the six parties, with the Action Party postponing its response for four days. The 22nd was the fourth day, and the message brought to Bonomi was that the Action Party had voted no. Such was the popular resentment of the King and Badoglio that sharing the people’s contempt could be turned into political gain. The Actionists, bruised and worn thin by the Koch Gang’s recent arrests of its leaders, stood resolute in excluding the monarchy from any new government until the question could be decided by the people of Italy in free national elections. Moreover, invoking its unity pact with the Socialists and Communists, the Action Party showed its partners why it made sense to withdraw their yes votes, and they did. Faced with what he called in his diary entry that evening the “truly unexpected,” Bonomi was ready to admit his failure to unify the CLN against the occupiers and quit.5

A SENSATIONAL report on the 22nd in the Fascist-run Rome daily Il Messaggero suggested that the Germans might soon withdraw from Rome.

Journalist de Wyss wrote in her diary, “Something is brewing.” The Messaggero article was based on a leak from the German press attaché, who, she went on, apparently “said too much or said it too soon.”6 Other than to note the rapid spread of the withdrawal rumor and the general excitement that because of a German withdrawal the Allied bombings might end at any moment, de Wyss had nothing further to say.

But the Vatican’s open-city negotiations with the occupiers had in fact entered a crucial stage. The coming warm weather was expected to bring an Allied counteroffensive, a strong inducement for Kesselring to abandon his stubborn defense in the south and shorten his supply lines by withdrawing from Rome. The efforts of the Holy See to convince the Germans to demilitarize Rome so that the Allies would halt their air raids was taking on a new logic. The Vatican was preparing for its long-sought orderly departure of the present occupants of the Eternal City. Months back, Cardinal Maglione, for one, had conceded that this transfer of power would be decided by military considerations and little else. The Pope’s only concern, Maglione told both Osborne and Tittmann, was that there be no hiatus, no political vacuum that the “communists” would fill. Only a seamless transition, melding the German departure and the arrival of the Allies, could thwart such a design. The Holy Father, however, did have one specific wish. Osborne had reported it to the Foreign Office on January 26:

The Cardinal Secretary of State sent for me today to say that the Pope hoped that no Allied colored troops would be among the small number that might be garrisoned at Rome after the occupation. He hastened to add that the Holy See did not draw the color line but it was hoped that it would be found possible to meet the request.7

In the light of a Roman spring, the time to decide the open-city issue seemed at hand. On March 22, what that decision might be appeared moving precisely on the course so carefully set by the Holy See.

IN A new but temporary hideout with a view of the Borghese Gardens, Peter Tompkins on that evening of the 22nd received his first details of the fate of Cervo. Tompkins had been on the run for nearly a week, unable to communicate with OSS headquarters, and the only further word about Cervo he had had in the meantime was that Cervo had been betrayed by Radio Vittoria operator Bonocore. What else Bonocore knew and had surely divulged was a frightful mystery no less than Cervo’s capacity to remain silent. Changing addresses almost nightly, the American took the name of Roberto Berlingieri, a nonexistent distant cousin to a Fascist noble family. He had the handmade Capri shoes and could affect the necessary Tuscan accent, and in that guise he had a chance encounter with someone who had had direct dealings with that family—Gestapo Captain Erich Priebke.

Luck was on Tompkins’s side, however, more than he knew. With Lele, he had gone to a crowded “curfew party”—a common all-night diversion in collaborationist circles of occupied Rome. This one was at the Parioli home of film star Laura Nucci, whom he recognized from the images of her silver-screen persona. Wrapped in furs, she lay on a sofa in a far corner of the room under the ambitious hands of a dapper SS officer. It was not until the next day that Tompkins learned that the SS man was Priebke, Kappler’s chief of counterespionage, and still later of his Berlingieri connections. But the American was unnerved more than once during the evening by Priebke’s intense stare. In the end, Priebke did nothing more than offer Tompkins his groping hand, click his heels while bowing slightly, and take his leave, walking a drunken zigzag to the door.8

News of Cervo had been brought to the Giglio family two or three days after his arrest. A boy had shown up at the Giglio home and spoken with Cervo’s mother and sister. The boy claimed to have been arrested with a professor and taken blindfolded to an apartment. He had heard people screaming, and when his blindfold was removed he had seen and spoken with Cervo. He was missing several teeth, the boy said, his face badly bruised and his lieutenant’s insignia ripped from his uniform. He had pleaded with the boy to go to his family, apparently expecting him to be released. The curious circumstances of the boy’s story aroused suspicion, but the next morning, Malfatti reported to Tompkins that his sources had located the apartment where Cervo was being held. His men had spotted what appeared to be three dead bodies taken from the building, where neighbors had complained of agonizing cries and gunfire every night. The building was near the Termini train station, at Via Principe Amadeo, 2. The apartment was in fact the site of what had been a dismal small hotel, the Pensione Oltremare, now refitted and refurbished as headquarters for the Special Police Unit of Pietro Koch.

ANOTHER man taken to the Koch Gang’s base along with Cervo and Mastrogiacomo, the houseboat custodian, was a police orderly named Giovanni Scottu, who had been assigned to Lieutenant Giglio that day. At war’s end, Scottu gave a sworn deposition of the torture undergone by his superior and himself as well. Detailing in precise and horrific language six disti...