eBook - ePub

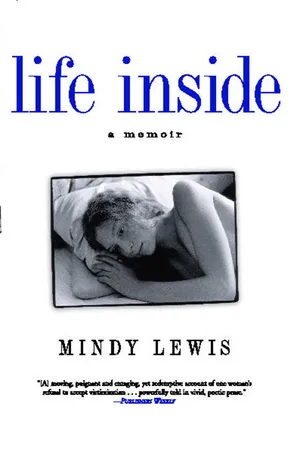

Life Inside

About this book

The patient is an ascetically pretty 15½-year-old white female. She is intelligent, fearful, extremely anxious, and depressed. Her rage is poorly controlled and inappropriately expressed.

Diagnostic Impression: Program for social recovery in a supportive and structured environment appears favorable.

Life Inside

In 1967, three months before her sixteenth birthday, Mindy Lewis was sent to a state psychiatric hospital by court order. She had been skipping school, smoking pot, and listening to too much Dylan. Her mother, at a loss for what else to do, decided that Mindy remain in state custody until she turned eighteen and became a legal, law-abiding, "healthy" adult.

Life Inside is Mindy's story about her coming-of-age during those tumultuous years. In honest, unflinching prose, she paints a richly textured portrait of her stay on a psychiatric ward -- the close bonds and rivalries among adolescent patients, the politics and routines of institutional life, the extensive use of medication, and the prevalence of life-altering misdiagnoses. But this memoir also takes readers on a journey of recovery as Lewis describes her emergence into adulthood and her struggle to transcend the stigma of institutionalization. Bracingly told, and often terrifying in its truths, Life Inside is a life-affirming memoir that informs as it inspires.

Diagnostic Impression: Program for social recovery in a supportive and structured environment appears favorable.

Life Inside

In 1967, three months before her sixteenth birthday, Mindy Lewis was sent to a state psychiatric hospital by court order. She had been skipping school, smoking pot, and listening to too much Dylan. Her mother, at a loss for what else to do, decided that Mindy remain in state custody until she turned eighteen and became a legal, law-abiding, "healthy" adult.

Life Inside is Mindy's story about her coming-of-age during those tumultuous years. In honest, unflinching prose, she paints a richly textured portrait of her stay on a psychiatric ward -- the close bonds and rivalries among adolescent patients, the politics and routines of institutional life, the extensive use of medication, and the prevalence of life-altering misdiagnoses. But this memoir also takes readers on a journey of recovery as Lewis describes her emergence into adulthood and her struggle to transcend the stigma of institutionalization. Bracingly told, and often terrifying in its truths, Life Inside is a life-affirming memoir that informs as it inspires.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I. LIFE INSIDE

INTAKE

THE TAXI ROLLS NORTH ALONG the West Side Highway, I sit in the backseat next to my mother, six inches of highly charged space between us. Turning my face away as far as possible, I look out at the Hudson River, the George Washington Bridge growing larger by degrees. I’m filled with conflicting emotions: fear, anger, defiance. My life as I know it is about to end. They’re going to lock me up. And it’s all her fault.

My mother’s face wears a familiar shutdown blankness. For just a second I wish I could reach out and touch her, ending the war between us. I would revert to the nice, accommodating child I’d been, adoring my stately, beautiful mom. But it’s too late. On her lap is a folder containing papers and forms, among them the court order placing me in state custody. A suitcase in the trunk of the taxi holds my belongings. Aside from summer camp, this is the first time I will live away from my mother.

It’s been a busy day. We spent the morning at the Department of Child Welfare Services. Our destination: Family Court. With each click of my mothers high heels against the tile floor I ambled more slowly, dragging my feet, trying to dispel the middle-class aura that surrounded us. My fashionable mother and my bedraggled hippie self stood out among the welfare mothers and others who had fallen through the socioeconomic cracks. When our turn came to appear before the judge, my mother pressed charges against me for truancy, smoking marijuana, and unmanageable behavior. The judge raised her eyebrows at me before placing me on Court Remand, making me an official ward of the state.

As the cab swerves onto Riverside Drive I see the yellow-brick building, it’s windows staring like blank, unreflecting eyes, I imagine this is how convicts feel on their way to the electric chair, at once suspended in time and rushing inevitably forward. But in some way, I know this is what I want—to cut the cord, get away—even if I have to go all the way to hell to do it.

The taxi turns onto West 168th Street and rolls to a stop. My mother pays the driver and turns to me.

“Let’s go,” she says, as if there’s a choice, but I’ve already slammed the door against her voice.

“Mindy was always a well-behaved child, but lately she’s stopped performing.” My mother addresses this remark to a small group seated on plastic hospital chairs: three psychiatrists, a psychologist, a social worker, a nurse. As my mother pronounces this last word—performing—I stiffen in my chair. Does she think I’m some sort of puppet?

It is December 6, 1967, three months before my sixteenth birthday. We are gathered for my intake conference at the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. Because P.I. is a teaching hospital, it’s supposed to be better than the other state hospitals. Dr. L., my former shrink, said I should consider myself fortunate to be accepted here. He said I’d be part of a community of others like me: adolescents and young adults, mostly from middle-class backgrounds, unable to cope well enough to continue living with their families.

“Your education won’t be interrupted. There’s even a school on-site,” he’d added, then wished me luck and shook my hand as if I were going off to college.

The hospital agreed to accept me on the condition that I’m placed on Court Remand, so my mother, in a moment of weakness, will not have the power to sign me out. Here I will remain until they decide to discharge me, or until I turn eighteen, whichever comes first.

“She could be here as little as six months,” one of the psychiatrists reassures my mother.

My heart pounds defiantly, each beat the slamming of a door. I had seen the impending date of my admission as a token of a battle won, a badge of victory in my rebellion against my mother and the mundane conventionality I despise. Until this moment, it has never occurred to me that I would have to live, as usual, through each day.

The Institute is built into the side of a cliff along Riverside Drive. The main entrance is on the tenth floor; to get to the fifth floor, you must descend. We live underground, nestled into rock. On one side locked windows overlook the Hudson; on the other is a wall of stone.

Up to thirty men and thirty women live on one floor divided into two mirror-image halves. On each side long hallways, their walls uninterrupted by artwork or decoration, connect two dorms, five private rooms, a bathroom, a shower room, a utility room, a locker room, an isolation room, a nurses’ station. The North and South sides converge in a central area (Center) where patients sit around in couches and chairs. From Center it’s a few steps to the kitchen and dining room, the elevators and locked staircase, and two living rooms that house TVs, a Ping-Pong table, a piano, and heavy, padded chairs and couches upholstered in orange, gold, and green vinyl.

The intake conference was almost more than I could bear, everyone talking about me as if I weren’t there. My stepfather showed up and spouted his bullshit. And my mother—so charming, so innocent, with her high heels and makeup. What a hypocrite! She tried kissing me good-bye, but I walked away. Then I was fingerprinted, like some kind of criminal, by a little bald man in a white jacket wheeling a squeaky portable fingerprint cart. Kafka would have loved it.

As I walk down the corridor I trail my fingers along the wall, afraid that if I’m not touching something solid, I might just float away. Walking next to me, slightly ahead, is my new psychiatrist, Dr. A., a clipboard tucked under his arm. At the end of the hall, he unlocks a door, flips a switch to turn on the overhead lights, and steps aside to let me enter.

The room is just like all the other rooms in this place. Just … bland. Beige walls. The same heavy padded chairs I saw in the living room. Hot air hisses from the radiator. It’s stifling. I ask if he can open a window.

“I don’t see why not.” He searches for the key that will unlock the wire gate over the window, then pushes the window diagonally out, just a crack. The window reflects the lit room, so all I can see of the sky is a little strip of blue.

Dr. A. seats himself and gestures to me to sit across from him.

“For the next seven months, I will be your psychiatrist.”

Seven months. The minutes are so long. How will I survive seven months?

I look him over. It’s hard to tell how old he is. Maybe in his late twenties, with blue-gray eyes and curly blond hair. I’d prefer it if he weren’t so good-looking. How am I going to talk to him? Even if I wanted to talk to him, I don’t know what I’d say.

I chew the threads hanging from the cuff of my favorite sweatshirt, comforted by it’s soft, tattered familiarity. Nestling my face in the crook of my arm, I breathe the faint smells of laundry soap and cigarette smoke, smells of home. I breathe deeper and catch the tiniest whiff of fresh air, rain, and trees. Then it disappears. All that is behind me. Now I’m a blank. Now I’m truly nothing.

Dr. A. sits there, watching me. Does he think he can tell from the outside what goes on inside of me? Like how scared and lonely I am right now, here in this place where I don’t know anyone, where all the doors are locked and the sky is a little stripe.

Who is he, anyway? I steal another look. Dr. A. wears a white jacket over his blue pin-striped shirt and red tie, and a gold wedding band. Red, white, and blue—real straight, like some kind of narc. He’s cleanly shaved, combed, proud of his appearance.

I look down at myself, at the holes in my sweatshirt, and feel ashamed. I don’t want him to look at me. I tuck my feet up under me and hug my knees.

Dr. A. opens a file folder and looks through it. A thin folder, containing all there is to know about me. He takes out a pen and writes something on his clipboard—probably something about how “sick” I am. Does he think he’s going to “cure” me? I want to tell him this is a masquerade that’s gone too far. But it’s too late.

He gets down to work, asking me questions about my childhood, my parents’ divorce, what kinds of drugs I’ve taken. He writes down my answers carefully, barely looking at me. When he’s finished, he asks if I have any questions. Just one: When can I go outside?

“We’ll see,” he says, and falls silent. The sound of his breathing makes me queasy.

He gets to go home at night, but I have to stay here. I hate him, just like I hate the stupid plastic chairs we’re sitting on and the ugly blandness of everything around me.

I prefer the heat of anger to the cold paralysis of fear. Riding my anger, I’ve succeeded in getting away from my mother. I thought this was a kind of victory. Now I’m not so sure.

Dr. A. leans forward. “Did you want to say something?”

I give him my worst malevolent smile. “Fuck you,” are the only words I can find.

MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION

The patient is a tall, slender, ascetically pretty 15½-year-old white female with long dirty blond hair which hangs down to her shoulders. This together with her dark stockings and turtleneck sweater contributes to her image as “hippie.” While conversing with me it was quite obvious that she is more genuinely wrapped up within herself. She toys with her hair, unconsciously and aimlessly, winding strands about her fingers. She is very self-conscious and is usually unable to face the interviewer. Rather she hides behind her hair, peers off into space or buries her face on her chest. Her walk is a sort of bedraggled shuffle which makes me think of someone being led off to their execution. She smokes a great deal.

She is sullen and for the most part nonverbal. Her responses are quite unpredictable. She can be cooperative, helpful and verbal at one moment, and then suddenly she’ll refuse to answer a question entirely or tell me that the query was “God-damned stupid.” Her profanity comes in bursts, often corresponding to rises in her anxiety. It is as if she uses it part of the time to shock, and dares the therapist to curtail her.

The patient is fearful, extremely anxious and depressed. At times her anxiety rises to such heights that she begins to tremble. Occasionally she smiles or giggles inappropriately. Her rage is generalized, poorly controlled and inappropriately expressed. The patient is well-oriented in all spheres. It is presumed her intelligence is above average.

Doctor’s Orders: E.O. in pajamas. Restrict to ward. No privileges. No phone calls. No visitors.

—Arthur A., M.D., NYS Psychiatric Institute

I’m delivered back to the head nurse, who tells me to get undressed for a medical exam and unlocks a closet-sized room next to the nurses’ station, I change into a hospital gown and sit shivering on the exam table. My hands are blotchy purple, and sweat trickles down my sides. The door opens, and in walks Dr. A. I can’t believe he’s going to examine me! I don’t want him to see me without my clothes.

Dr. A. presses a stethoscope to my chest and leans in close. I look up, away, anywhere but at his face, holding my breath to slow my heart, which is beating too fast. I hope he doesn’t think it’s because he’s close to me. He looks in my mouth with a little flashlight and tells me to stick my tongue out, but it’s hard to do without it shaking. Even my tongue is out of control! He shines a light in my eyes, then sticks an instrument with a tiny light into my ear. I imagine the light shining in one side and out the other. I try to resist an urge to laugh, but it comes curling out the edges of my mouth. Why do I think such stupid things? Maybe he really will find something wrong with me. Maybe I’m brain-damaged from all the drugs I’ve taken.

Dr. A. scrapes a needle along the bottom of my foot, leaving a long scratch. I stare at the thin line seeping blood, then at him. “Sorry,” he says. “Just testing your reflexes.” There must be something wrong with my reflexes. If they’d been working right, I would have pulled my foot away, or kicked him. I hope he’s a better shrink than he is a doctor.

The nurse comes in and hands me a pair of cotton hospital pajamas. She gathers up my clothes and explains that for the time being I am on observation so they can make sure I don’t run away. I tell her I won’t wear them. They’re pink—I never wear pink—and too small, besides. I follow her to a closet filled with stacks of folded pajamas. I choose a pair of pastel green, size large. The sleeves hang over my hands, which is fine with me—the more that’s hidden, the better.

I ask for my cigarettes. The nurse pulls from her pocket an enormous bunch of keys, unlocks a cabinet and finds the carton of Marlboros marked with my name. She removes a pack, hands it to me, and offers me a light. She puts the matches in her pocket and locks the cabinet. Everything here is under lock and key, including me.

“Can’t I have my own matches?” I’ve been here two hours, and I can’t open a window or wear my own clothes. Now this. It’s worse than being a child.

“Not yet.” She puts her hand on my shoulder, but I pull away.

“Fuck you!” I can’t seem to come up with anything else today.

“That’s not a nice thing to say” the nurse says.

Good, I think, because I am not nice. Once I was a nice little girl, but those days are over. Before I can stop it, that nice little girl’s tears fill my eyes. I blink them away, hoping nobody saw.

The nurse shows me the dorm where I will sleep. Ten beds line the walls, beside each one a dresser, like a stripped-down version of some children’s story—Snow White or Madeline, Only a few personal possessions are allowed on top. Here and there stuffed animals sit on hospital bedspreads, huddled together: silly little-girl things, symbols of nonexistent comfort. I arrange my books on top of my dresser to remind myself who I am. Since I’m not allowed my clothes, all I have to put away are socks and underwear, shampoo and soap. As I put them in the empty dresser drawers, I have a sense of how little space my life takes up.

I wait outside the nurses’ station. With its large windows, it’s like a glassy eye, always watching. The head nurse scribbles in a book. I hate her, her stupid curly hair, her fat ass. Every once in a while she looks up at me. I’ll have to give her something interesting to write about, something she can really sink her teeth into. I open my eyes wide and give her a hateful stare.

A girl with long brown hair comes over and says hello, a stupid smile on her face. She says if I have any questions or need any help to ask her. Maybe she’s in cahoots with the staff. I stare just past her, then turn my face away. I won’t conspire with the enemy. If I have to be here, I’ll just be a body, a piece of matter. I won’t talk to anybody.

I can’t take another minute sitting out here in the hallway. Privacy is as important to me as air, and I’m suffocating. I jump up, knock on the nurses’ station door, and ask permission to sit in the little room at the end of the hall. The nurse answers yes, as long as I keep the door open. What does she think I’m going to do in there, commit suicide by hitting myself with my book?

Fortunately nobody else is in the end room, just a table, two chairs, a lamp, me, and my book—Pär Lagerkvist’s The Dwarf, about a twenty-six-inch-tall servant/adviser to a princess, who secretly despises and mocks those people who seek his counsel. He considers himself one of a superior race, beyond reproach even after committing a treasonous crime.

I sit here in my chains and the days go by and nothing ever happens. It is an empty joyless life, but I accept it without complaint. I await other times and they will surely come, for I am not destined to sit here for all eternity…. I muse on this in my dungeon and am of good cheer.

I close the book. As much as I’d like to emulate the dwarf’s acceptance of his fate, I’m afraid. I cannot see my future.

TESTING

THE TEST YOU ARE ABOUT TO TAKE is in three parts and will take about three hours.”

The psychologist, Miss M., is too perky for her own good. Her voice is too friendly, too singsong, like she’s reading from a script. She tells me she’ll be giving me an IQ test and some psychological tests.

“Some of it will be fun,” she says. When I don’t smile back, her face goes tight.

If there’s one thing I hate, it’s phoniness. It’s obvious her niceness is fake. She’s just one of a long line of social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists who pretend to be friendly but are really just trying to figure me out. They think they can measure my intelligence, measure me. I don’t want to take their damn tests! I’m here. Isn’t that enough?

She places some paper and a pencil in front of me and asks me to draw a person. It’s hard enough to draw people when I’m looking at them, but when I have to draw them from imagination or memory they come out looking like stick-figu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- I. LIFE INSIDE

- II. LIFE AFTER

- A Note to the Reader

- Acknowledgments

- Selected Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Life Inside by Mindy Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.