![]()

PART ONE

The Insight to Growing Brands

![]()

Chapter 1

Brand Growth:

Challenging Times

‘If you can find a path with no obstacles, it probably doesn’t lead anywhere.’

—Frank A. Clark

The pursuit of profitable growth unites brands regardless of their size, cost or nature. Yet this pursuit has never been more challenging. Understanding the reasons for these challenges will shed some light on how to overcome them.

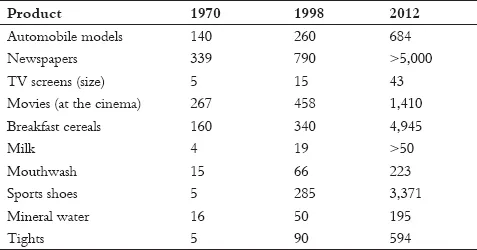

We live in an era of brand proliferation, with every market fragmented and crammed with brands. Consumers are not just spoiled for choice, they are befuddled. Figure 1.1 shows the extent of brand proliferation between 1970 and 2012 in the USA alone. If you wanted sports shoes in 1970 you had a choice of 5 items; in 1998 you could select from 285, and by 2012, there were over 3,000 options vying for your attention!

We’re also in the midst of a difficult economic period. Over the last few years, global GDP (gross domestic product) growth has slowed to between 2 and 3 per cent annually; many consumer categories are flat or declining. War, terrorism, and natural disasters are adding to economic woes. Under such circumstances, brand growth is under pressure.

Figure 1.1Trend in Product Variety (Number of Models) for Some Products in the USA

Source: Cox, M.W.; Alm, R. (1998, revised 2013); ‘The Right Stuff: America’s Move to Mass Customisation’; Annual Report of Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Lastly, we’re in the digital era. The explosion in the use of the internet through personal computers in the early 2000s, and recently through smartphones, has transformed consumer behaviour. The website Internet Live Stats1 estimates, as of December 2016, that of the 7.4 billion people on earth, an estimated 3.5 billion have access to over 1.1 billion websites on the internet today. A recent study (Salesforce, 2014) showed that 85 per cent of consumers believe the mobile phone is an integral part of their lives and spend an average of 3.3 hours per day on it. A large ten-city survey reveals that 79 per cent of smartphone users reach for their phones within 15 minutes of waking up (Adweek, 2013).

Unsurprisingly, this digital explosion has made the lives of already busy consumers ridiculously hectic. Consider the things that have always kept people preoccupied: working, playing, exercising, spending time with the family, and maintaining social connections. But today, consumers are doing all of that while being digitally engaged—sharing information, shopping, playing games, browsing, and so on. To capture the attention of such distracted consumers is extremely difficult for any brand (especially when it is competing with hundreds of brands trying to do the same thing).

The Decline of Mass Marketing and Advertising

From a marketing point of view, one could say that the 1980s and 1990s were the advertising decades. This was the time when big brands invested in brilliant advertising, which in turn made them bigger. In this period advertising evolved from communicating a simple, functional benefit—‘washes whiter’, ‘fits better’ or ‘lasts longer’—to appealing to the consumer’s emotions. For example, the Procter & Gamble (P&G) deodorant Sure, instead of talking about long-lasting protection, challenged you to ‘raise your hand if you’re sure’ through an engaging, musical television advertisement showing people in different, physically demanding situations raising their hands with confidence.2

The 1980s and 90s, consequently, were a heady time for the advertising industry. As Ian Leslie, a veteran ad man and writer (Leslie, 2015), puts it, ‘We made famous stuff, and we made stuff famous. Every ad in the Levi’s campaign, for instance, with its combustible blend of sex, music and Americana, was a national event.’

While being a sensational time for the ad agency, it was a worrisome time for the marketing company, typified by its Scrooge-like finance director. First, the enormous amount of money spent on advertising was viewed as wasteful and excessive. When an after-shave brand advertised on the TV show Friends, for example, it reached a large section of its target audience. But Friends was also viewed by thousands of men not interested in buying an after-shave in the near future (as well as thousands of women unlikely to ever be interested in buying an after-shave!)—so the brand was paying to reach people it didn’t need. Second, most companies did not employ sophisticated advertising testing and post-advertising tracking, and so were never sure about the impact of this massive expenditure.

With the advent of digital media and their ability to target end users precisely and measure results easily, companies have begun viewing creative TV campaigns as inefficient, wasteful, and even primitive. Digital marketing has made it very easy for marketers to reach the right consumers—exactly the ones they want—for example, the ones who have shown an interest in, or have purchased, their brand. Even as consumers are looking for information on a product category or searching for something related, marketers get precise data—they count how many people saw the message (‘impressions’), how many of those who saw it clicked through to get more information, and, in some cases, how many of the clickers actually bought the brand. With the help of this framework, the after-shave brand cited above could target potential as well as existing users close to when they’re thinking of buying an after-shave. Company executives might argue that they could keep such loyal fans of the brands engaged through a website and social media platforms, where the brand could have interesting two-way, tailored dialogues with consumers.

The digital medium has also made it possible to sell directly to consumers. Through e-commerce, people can click their way to purchases without visiting a physical store.

In fact, the digital medium seems to align itself with—and indeed, bolster—some commonly held perceptions about consumers and brands.

Commonly Held Perceptions about Consumers, Brands, and Brand Growth

Here are five impressions about consumers, brands, and brand growth.

1. People are rational. Consumers evaluate brands carefully. They believe these brands are different from each other and remain steadfastly loyal to their favourite brands.

2. Brand growth comes from getting heavy and loyal consumers to use more. Light and very light users who buy a brand infrequently don’t matter. And retention (of existing customers) is cheaper than acquisition.

3. Brand growth can come not only by expanding the number of users (reach), but also by increasing usage (buying frequency). A small brand can hope to have higher usage than the market leader.

4. Long-term growth can be generated by a series of discrete short-term activities. Retail brands need monthly promotions to draw consumers in and boost sales. Temporary price-discount promotions attract non-users, who, having tried the product, will be induced to buy it again, thereby generating incremental long-term sales.

5. With digital evolution, mass marketing is dying. Brands should divert precious funding from marketing to e-commerce and other digital platforms to drive brand growth.

I’ve heard different versions of these statements uttered with conviction, as if they were the absolute truth. And for these reasons, many brands are increasingly focusing on loyal consumers, investing in brand engagement through social media, doubling up on e-commerce, and reducing their investment in classical brand advertising.

Unfortunately, all these statements are false. The next chapter will show you why, and also explain the real source of brand growth.

SUMMARY

– Brands today face many challenges on their path to achieving profitable growth. They operate in highly competitive markets, often in precarious economic conditions. And they have to reach consumers who are very busy and spend a lot of time engaging with the digital medium.

– In response to this, and because of a few commonly-held beliefs, marketers are moving away from classical advertising and mass marketing, investing instead in programmes focused on loyalty, retention, e-commerce, and brand engagement. But these beliefs are false! So basing decisions on them is wrong.

1You can visit the website at <www.internetlivestats.com>, accessed on 21 December 2016.

2You can watch the deodorant Sure’s commercial on YouTube, at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-FZ21uDKeQ>, accessed on 21 November 2016.

![]()

Chapter 2

Consumers and Brands:

Myth and Reality

‘Stubbornness does have its helpful features. You always know what you are going to be thinking tomorrow.’

—Glen Beaman

Proof that the five core beliefs described in the previous chapter about consumers, brands, and brand growth are myths is offered by robust research in the area of social psychology by experts like Daniel Kahneman and Jonathan Haidt, and by the researchers at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute of Marketing Science.

People Are Rational

The belief that people are logical creatures leads to the conviction that, as consumers, they spend time thinking about and evaluating brands carefully.

Unfortunately, we are not as rational as we think we are or want to be. In his brilliant book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman explains how all of us have two systems of thinking. System 1 is automatic, intuitive, quick, and emotional. We use it with little effort; indeed it operates on its own and often without our knowledge. System 2 is logical, reasoned, and rational. We use it to make assessments and decisions (Kahneman, 2011). The surprising thing is not the existence of two systems but the fact that it is the intuitive System 1 that dominates our thinking. If we were to borrow an analogy from films, System 1 is the conquering hero, while System 2 is the helpful, but often ignored, sidekick.

In The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Religion and Politics, Jonathan Haidt offers compelling insights into this area. He explains that intuition always come first, strategic reasoning second. Often we use strategic reasoning (Kahneman’s System 2) to justify our already-held intuitive, preconditioned beliefs (Kahneman’s System 1). Haidt draws the analogy of the rider (logic and reasoning), trying to control the elephant he is on (intuition and emotion), but only being able to do it to the extent that the elephant wants to be controlled. When the elephant turns right, for example, the rider quickly steers the elephant to move to the right. In other words we use reasoning and logic (constituting about 1 per cent of our thinking) to justify—often, and on the fly—our pre-held views (the other 99 per cent).

How does this relate to brands? Well, if we rely on intuitive thinking for the big issues that we face in the realms of religion, politics and morals, it is wildly unrealistic to imagine that we would use reasoning and logic to select brands. After all, choosing which toothpaste to buy is a trivial decision, much more likely to be handled by our hyperactive, always-on System 1—our elephant.

Evidence supports this. Talking about how we choose brands (Romaniuk, 2016), Jenni Romaniuk says:

The thoughts and actions of buying are typically these:

• instantaneous, without (much) conscious deliberation

• influenced by context, which defines which part of memory is triggered

• inconsistent, in that today’s retrieved thoughts are not necessarily retrieved tomorrow.

She then talks about how we use ‘cued retrieval’ based on the external environment (for example, the desire to consume a soft drink when outside on a hot day), which facilitates a quick, intuitive decision. In another study (Romaniuk, Sharp, and Ehrenberg, 2007), Romaniuk concludes that: