eBook - ePub

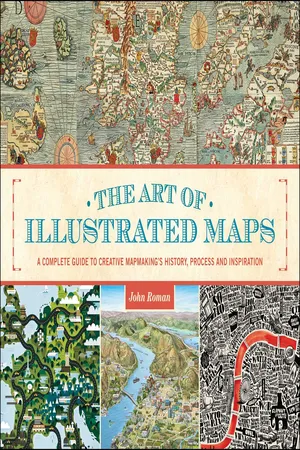

The Art of Illustrated Maps

A Complete Guide to Creative Mapmaking's History, Process and Inspiration

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Art of Illustrated Maps

A Complete Guide to Creative Mapmaking's History, Process and Inspiration

About this book

While literally hundreds of books exist on the subject of "cartographic" maps, The Art of Illustrated Maps is the first book EVER to fully explore the world of conceptual, "imaginative" mapping. Author John Roman refers to illustrated maps as "the creative nonfiction of cartography," and his book reveals how and why the human mind instinctively recognizes and accepts the artistic license evoked by this unique art form. Drawing from numerous references, The Art of Illustrated Maps traces the 2000-year history of a specialized branch of illustration that historians claim to be "the oldest variety of primitive art." This book features the dynamic works of many professional map artists from around the world and documents the creative process as well as the inspirations behind contemporary, 21st-century illustrated maps.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Art of Illustrated Maps by John Roman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

A LOOK BACK: MAPPING THE ORIGINS OF ILLUSTRATED MAPS

“It is the duty of a true poet to take the fragmented world we find ourselves in, and make unity of it.”

—ROBERT A. JOHNSON

A SKETCHY PAST

Technical geographic land and sea maps have a very long history, spanning well over five thousand years, which makes it difficult to understand why absolutely no books at all existed on the subject of maps until Lloyd Brown’s The Story of Maps was published in 1949. Scholars and collectors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had an interest in maps, but until Brown’s book appeared, only a handful of papers, studies and treatises made up the entire literary extent of mapmaking’s past. The limited body of reliable documentation on ancient mapmaking hindered map historians, and the sheer lack of physical examples of old maps made such a history unattainable.

Over the centuries, maps of any country or land were dangerous documents if they fell into the hands of potential enemies, so they were carefully guarded or intentionally destroyed. Most antique maps perished by decay, fire or at sea aboard ill-fated ships. Those drawn on surfaces that could be reused (animal skins for example) could be scraped off and recycled for other needs. Maps on metal inevitably rusted away, and those on wood deteriorated over time.

In addition, mapping the earth failed to become a high priority to governments in earlier centuries. A country’s need to attend to food, infrastructure and commerce, not to mention plagues and wars, left little time, energy or resources for the creation of maps. The few maps produced, and the little remaining of antique maps for study, were hidden away in private collections across the world.

The arrival of World War II in 1939 changed all that. The theater of war created an immediate demand for any information regarding the terrain of Europe, Africa and the Far East. Maps acquired and utilized by the military in the 1940s were useful for the most part, but their lack of uniformity, their geographical errors, and the fact that many of the maps were obsolete created a serious demand for the cartographic efficiency that we’ve become accustomed to today.

Over the centuries, maps of any country or land were dangerous documents if they fell into the hands of potential enemies.

In 1932, the English geographer Kenneth Mason is quoted as saying, “I doubt whether a hundredth part of the land surface of the globe has been surveyed in sufficient detail.” During and after the war, however, world governments turned their scholarly and scientific attention toward accurately mapping the world. As a result, we owe to this short period of history a little over half of a century incredible advances in mapping as well as a vast body of new historical research that has helped us to more fully understand cartography’s legacy.

Like geographic maps, the creation of illustrated maps also has a long history, spanning nearly two thousand years, and this subject matter also lacks significant published historical or analytic review. The Art of Illustrated Maps charts previously unexplored ground as it traces the birth and evolution of the highly specialized order of cartographic art known as illustrated maps. Mapmaking as a whole is an interwoven and complicated subject that stands totally apart from this book’s specific mission. Our path will follow a limited, finite route through time, a singular path that will enable us to unearth only those people and events pertinent to the forging of illustrated maps as the unique, creative branch of cartography that it is today.

SPLIT-BRAIN INFLUENCE ON MAPS

Maps speak to us with graphics and icons that have changed little throughout cartography’s history. A consistent symbolism existed in all antique maps, with only the topics of maps changing over time. According to historian R.A. Skelton, “During the last seven centuries the map reader has had to adapt himself to change far less than the book reader.” In addition, researchers comparing examples of primitive maps have concluded that from the outset, there were two distinctly different ways maps were created, and these two methods, like the surviving map symbols, have remained with us right up to our modern day.

Primitive mapping, without doubt, got its initial start presenting the world as idea. In time, some felt a need to express the world as object. Two alternate interpretations of the same reality emerged in those prehistoric times, and each mode of expression coexisted, creating disparate maps of the habitable world. Obviously, historians do not look back and credit either variety of antique map as being the correct method. Be that as it may, an interesting side note (which is comforting on some level), is to see that these very same polar opposite creative approaches are still alive and well today. These opposite approaches perform a tug-of-war in the contemporary art professions; they highlight the subtle frictions that exist between the abstract and representational arts. So it seems that there is more going on here than two contrary artistic styles. A logical explanation might be that each side of the human brain is at work—the left brain in some artists and the right brain in others—each making itself known. Each side of the brain expresses itself, each contributes to the pool of information, and each attempts to make unity of the world in which it lives. This reasoning can be applied to both eras, then and now.

Inspired by the Nobel Prize–winning split-brain experiments of Roger Sperry in 1981, art teacher and author Betty Edwards gave us a wealth of information on brain hemispheres and their roles in the creative process in her groundbreaking book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. Edwards claims that the left-brain oversees linear/technical examinations of its surroundings, and the right brain is involved in conceptual analysis.

Neurologists have not challenged Betty’s theory, but have disputed her sharp demarcation of brain hemisphere activities, stating these actions are more spread out and interwoven in terms of location within the brain. Edwards, in fact, acknowledged this quite early in her studies, and admitted to simply taking artistic license in transferring Perry’s scientific findings for the benefit of a nonscientific audience. Nevertheless, her division of the brain’s interpretive approaches to problem solving does exist, and regardless of how or where that division exists in the brain, it does in fact manifest itself in all aspects of life and is not limited to the arts.

The theory of brain hemispheres can provide us with a good model for analyzing the choices early mapmakers made with regard to their methods of mapping. The first individuals to create two-dimensional representations of their world produced kinetic replications of life, maps as ideas that were intended to move the viewer in some way. They depicted information in context to some aspect of unseen reality. They rendered their lands with respect to some belief or truth and with a disregard (or lack of awareness) of technical, measured accuracy. Marshall McLuhan, in Cynthia Freeland’s But Is It Art?, explains, “Primitive and pre-alphabetic people… live in a horizonless, boundless space rather than a visual space. Their graphic representation is like an x-ray. They put in everything they know, rather than only what they see.” He adds that their idea of art is multidimensional, a nonlinear way of thinking and expression. Such early maps, were any to survive, would be metaphors for a worldview, dealing with what should be, should not be, could be, ought to be. Like young children, the first map artists instinctively thought outside the box, as they were not even aware that a box existed.

Illustrated Map of the Cosmos on a Medallion

From Thrace (modern-day Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey) around AD 225 comes this bronze medallion that features an illustrated map of the universe. The cosmos is depicted in the center with a celestial view of the sky grounded by figures on the earth at the bottom. The inner map is flanked by early zodiac symbols in the border. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Theodora Wilbour Fund.)

The true science of cartography, on the other end of the scale, was slow in coming, evolving out of the now-obscure origins of prehistory. Celestial subjects were the first topics of depiction for primitive mapmakers. Babylonian and Greek studies of the stars during antiquity led to the development of the zodiac around 539 BC, but more importantly, to the amazing discovery in 523 BC that the earth was a sphere and not flat. This pioneering interest in the shape of the planet inspired further curiosity and eventually laid the groundwork for the more scientific cartographic work that was to come.

Celestial subjects were the first topics of depiction for primitive mapmakers.

Out of those early planetary studies, the inklings of presenting the world as object began to bloom. This new era of geographic mapmaking saw that no propositions in maps went beyond the physical. Their approach to mapmaking was static, to render and isolate the land as articulately as possible and to refrain from incorporating any unreal aspects of the mind. With this science-based restriction came the dawn of the true cartographic map, and the beginnings of the dividing line that would classify the differences between technical maps and illustrated maps.

Dozens of cartographers, mathematicians, astronomers and geographers are laced through the early years of mapmaking’s past, but only two prominent historical figures can help us piece together how illustrated maps originated. The first, Strabo, brought cartography out of its nonmathematical roots and set it on a scientific course. The second, Claudius Ptolemy, picked up where Strabo left off and was instrumental in divorcing illustrated maps from the “science” of mapping. From that point forward, the field of illustrated maps was on its own and was independent from the cartographic realm. Exactly how the ancient mapmakers reached that point is where our story lies.

STRABO

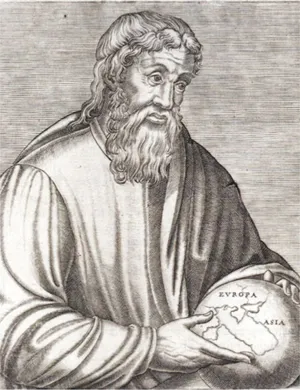

Strabo

Strabo, the pioneer of true geography and cartography.

(Courtesy Wiki Commons. Public Domain. Unknown Author. Portraits from the Dibner Library of the History and Science of Technology. Taken from Strabo’s Geographica, chapter 35.)

Cartographic historian Lloyd Brown states that there is really only one way to compile and plot a map as accurately as possible: go into the field and survey it. As obvious as that sounds to us today, Strabo and Ptolemy were the first geographical explorers to do exactly that: travel the known world for the purpose of learning the shapes and contours of the earth. These two geographers were separated in time by a hundred years or so. Both lived during the turn of the first millennium, both wrote extensively on geography, both were involved with world maps, and both worked in the Roman Museum and Library at Alexandria, the Egyptian cosmopolitan center of the Hellenic world.

Strabo, born in 63 BC in Amaysa on the shores of the Black Sea in present-day Turkey, gets the credit for closing the door on the approximate mapping of the pre-Christian past. Strabo’s writings on geography and cartography relied heavily on the discoveries of the ancients, but he made efforts to improve upon mapping techniques and gain a better understanding of the earth’s surface.

Born to a wealthy family, Strabo received an unusually extensive education for people of that time. In his youth, Strabo’s cartographic career took shape through training under the influential Roman geographer Tyrranion of Amisus. Strabo claimed to have traveled extensively in his early teens studying the earth and acquiring his specialized knowledge for his love of geography. Of all the geographers in the history of early cartography, Strabo is the single contributor who claims to have personally surveyed most of the known world (of that period) and compiled the largest extent of cartographic field studies.

Strabo and Ptolemy were the first geographical explorers to travel the known world for the purpose of learning the shapes an...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I. A Look Back: Mapping the Origins of Illustrated Maps

- Part II. Illustrated Maps: The Viewer, The Artist and The Mind

- Part III. The Creative Process of a Map Illustrator

- Part IV. A Showcase of Contemporary Map Illustration

- Conclusion

- Permissions

- Works Cited

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright