![]()

Chapter 1

The New Latin America

Get out of the way, India. Move over, China. Stand back, Southeast Asia. Here comes the new kid on the block, a reborn Latin America. Bursting with enthusiasm. Ready to erupt with a dynamism unseen in the Western Hemisphere since the Industrial Revolution. Latin America, exuding an economic exuberance that is sure to be the envy of the developing world. And U.S. exporters have seen this coming. Last year alone they shipped four-and-a-half times as much product to this region as they did to China, twenty-four times the amount they shipped to India, and twice as much as they shipped to the United Kingdom, Germany, and France combined.

But doing business in Latin America is not easy. A constantly changing landscape makes long-term strategies especially difficult. If there is one truism about this region, it is that if you don’t like the way the politics, economics, and social conditions are going now, wait ‘til tomorrow and they will change.

Latin America’s never-stopping politico-economic pendulum swings wildly to and fro. From dictators to freely elected presidents to elected autocrats. From liberal socialist governments to reactionary right-wing rule to populism. From hyperinflation to modest economic growth to rapidly rising prices. From shattered banking systems to stable financial markets to bank failures. From protectionist trade to free trade to the nationalization of entire industries. From isolation to open borders hungry for foreign investment to forced joint ownership of projects with government. Such a wildly swinging pendulum muddies the waters for trade and investment. Misunderstanding the North and misunderstood by the North, Latin governments and their citizens continue to ride the fringes of economic progress, unable to penetrate the psyche of either Republican or Democratic administrations in Washington.

Part of the problem is the enormous mixture of cultures that comprises Latin America and confuses Americans.

Mexico, the Caribbean nations, Central America, and South America—in fact, everything south of the U.S. border— comprise what we commonly call Latin America. Imposed by the Spanish conquerors of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Spanish language dominates the region, but other languages are also spoken. Portuguese is the official language in Brazil; it’s English in Guyana, Dutch in Suriname, and French in French Guiana. In the Caribbean, English, Dutch, French, and Creole are spoken along with Spanish. In Central America, English is the language of Belize. Spanish is official in all other countries. One-third of Guatemala’s population is indigenous and speaks a mixture of Mayan dialects.

Culturally, the region is equally mixed. In countries where Spanish or Portuguese is the official language, the Hispanic culture and Catholic religion inherited from Spain and Portugal are predominant. In Guyana, however, more than 50 percent of the population is descended from East Indians and practices the Indian culture and Hindu religion. In Haiti, a combination of French and African cultures has nurtured the Voodoo religion. The English-speaking Caribbean mostly consists of African descendants influenced by a European heritage, creating a unique West Indian culture that has welcomed Pentecostal preaching. Fidel Castro’s atheism and its penetration of the Cuban culture is unique in the region.

In Central America, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, as well as in certain parts of Brazil, mestizo is the predominant race. A mestizo is a person of mixed ancestry, especially of mixed Spanish or Portuguese and indigenous Amerindian.

Argentina is strongly influenced by descendants of settlers from Northern and Southern Europe, especially Italy and Spain. In the Caribbean, the United States owns a territory (the English-speaking Virgin Islands) and a commonwealth (Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico).

Size also matters, especially in the business world. Brazil dominates the region, with 186 million people and a geographic size equivalent to the continental United States. Its industrial base is very similar to that of the United States. Manufacturing, retail, and service industries are all healthy and growing. At the other end of the spectrum, Haiti and Nicaragua are the two poorest countries in the region with gross domestic product (GDP) per head of $1,600 and $2,400, respectively. These two countries, along with Bolivia and Suriname, stand in stark contrast to the sophisticated urban centers of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Santiago, Bogotá, and Mexico City.

Political upheaval and violence have characterized Latin America for centuries. Prior to 1989, when a democratic wave washed over virtually all Latin American countries, Peru had experienced only four years of elected governments, Ecuador eight years, Brazil one year, and Uruguay barely four months. Bolivia had gone through 180 presidents in 160 years. Peronist Argentina had been little more than a police state for seventy years. Paraguay’s iron-fisted president, Alfredo Stroessner, played host to thousands of Nazi war criminals. For two decades prior to 1960, Venezuela was governed by autocratic dictators. Between 1946 and 1966, more than 300,000 Colombians were killed by their own government. Even after 1989, under democratically elected governments, Brazilian police with automatic weapons wiped out scores of homeless children; Venezuelans twice rioted against their president and eventually elected a notorious autocrat; Peru’s Shining Path terrorists massacred Peruvians and foreigners at will; Colombian drug gangs, protected by the army branch of the Communist party (called Fuegas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or FARC), assassinated presidential candidates and judges, while bandits ruled mountain villages. Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua suffered years of right-wing and left-wing bloodshed, with death squads massacring indigenous tribes and squashing any and all resistance.

In such a setting, it’s easy to understand why managing exports to the region, sourcing materials or parts from Latin American suppliers, or opening and operating Latin American facilities are at best difficult tasks and at worst, nightmares. But cultural mores, political upheaval, and chaotic violence are only some of the reasons that doing business there is difficult. An array of other external market forces—that is, market forces beyond the jurisdiction of corporate boardrooms and the control of company management— determines to a very large extent the types of pricing, distribution, packaging, production scheduling, employee incentives, and financing policies that will work. These external forces create market environments that are as different from those in the United States, Canada, or Europe as night is from day.

What external market forces make Latin America such a challenge? Although the magnitude of each varies from country to country, the following seem to bear most heavily on business decisions:

•Government interference

•Foreign-exchange controls

•Trade pacts

•Barely functional court systems

•Closed business cartels

•Thriving underground economies

•Antiquated banking systems

•Open corruption in both public and private sectors

These conditions create rapidly changing, confusing, and often hostile market environments that, more often than not, demand decisions at variance with your organization’s domestic objectives. They cause business climates to be turbulent, unpredictable, and very unforgiving. Managerial errors are not tolerated. Latin American markets are anything but user friendly, as American markets tend to be.

Because these external forces are so powerful, marketing strategies that actually bring expected results must be broad, long term, and very flexible. You must be ready, willing, and able to make changes in pricing, distribution, packaging, promotions, and even product design as market forces dictate.

You must court government officials at various levels, sharply differentiate between social classes and gender, and adapt to cultural dissimilarities. You must take care of recalcitrant customs officials, union bosses, and influential intermediaries. And to accomplish these feats, you must work through local partners.

With such a staggering number of external forces, plus the wide range of cultures, languages, and religions, it’s very difficult to look at Latin America as a single market. Instead, it must be viewed as a conglomeration of markets, peoples, and cultures, each unique, yet all similar. Each is worthy of individual assessment, yet all suffer from lack of attention from the U.S. government. Fortunately, U.S. businesses large and small look to Latin markets with increasing optimism.

To understand Latin America, one must first recognize the radical changes that have occurred since 1989. By so doing, and accepting the fact that no one in Latin America wants to turn the clock back to pre-1989 times, you will understand how economically powerful Latin America could be in the future. The Lost Decade of the 1980s was the turning point.

The Lost Decade

The turbulent, bloodletting decade of the 1970s and the so-called Lost Decade of the 1980s are in the past. The experiment in democracy of the 1990s proved at best confusing and at worst disruptive. During the early 1990s, conditions in most Latin American countries resembled the Wild West of the United States in the late nineteenth century. Political, social, economic, and financial institutions were being reinvented, while social disorder, chaotic political maneuvering, and decrepit infrastructures tore at the very fabric of the region. But the nations of Latin America survived their essay with autocratic governments, military holocausts, and protectionist economic policies. They passed through the idealistic phase of democratic ideology and began to taste the benefits and dangers of freely elected governments.

All Latin American nations are now moving toward their rightful place in the global economy. This region is no longer a backwater. Its citizens are no longer wrestling with military rule, state-controlled economies, and unworkable democratic administrations. Latin America has, indeed, evolved beyond inexperienced exuberance. In virtually all countries, political institutions, financial systems, and environmental and social awareness have matured. In fact, it’s safe to say that some Latin American countries have evolved well beyond what many have called developing economies and are now approaching developed country status.

Every country except Cuba now has a working democratic government. Maybe they aren’t all working as well as we would like—Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador come to mind—but all heads of state and legislative bodies have been duly elected in multi-party political campaigns.

Financial institutions in most countries are relatively stable. Yes, some of the smaller Caribbean states, as well as Bolivia and Ecuador, have a way to go before their banking systems are able to handle much in the way of trade or project financing. But all nations have weathered the storm of currency devaluations. In Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Chile, the capital markets and banking systems are on more solid footing today than in recent memory.

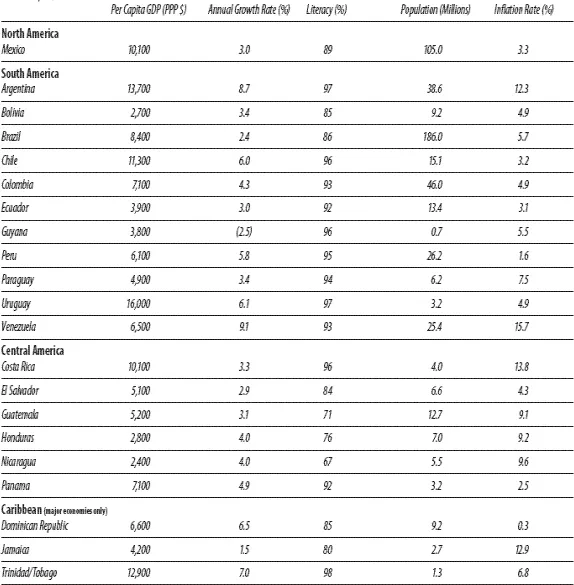

At the macroeconomic level, hyperinflation has disappeared, although in two-thirds of the region inflation is still much too high. In Argentina, Venezuela, Costa Rica, and Jamaica, high interest rates continue to delay much-needed investment in infrastructure projects and manufacturing plants. However, with stability in capital markets and the absence of new shockwaves from foreign currency devaluations, interest rates should eventually come down throughout the region. Table 1-1 shows GDP per capita in purchasing power parities and other key statistics for each country.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) purchasing power parities (PPP) are “currency conversion rates that both convert to a common currency and equalize the purchasing power of different currencies. In other words, they eliminate the differences in price levels between countries in the process of conversion.” Economists believe this presents a truer picture of economies than traditional GDP per-capita calculations. Perhaps PPP is a little easier to understand when one thinks of it as a mechanism to state that exchange rates between two countries are in equilibrium when the purchasing power for a given basket of goods is the same in the two countries. The Economist magazine issues its McDonald’s Big Mac Index once a year. This hamburger index, otherwise known as the Big Mac PPP, is the exchange rate that would leave a hamburger in any country costing the same as in the United States. You can find a thorough description of the Big Mac PPP in the March 27, 2004, issue of The Economist.

Table 1-1 | Key Statistics

Source: Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State, 2004 and 2005; CIA World Factbook

Intra-region trade is at its highest level ever. Trade balances are still reasonable. Fiscal discipline has returned to most countries. At the political level, all Latin American governments, even Argentina, have reacted positively to International Monetary Fund (IMF) mandates for economic reform.

Washington may be preoccupied with the Middle East and China, but American businesses are excited about opportunities in the south. Exports from the United States to Latin America, including Mexico, have grown 12 percent over the last five years. Excluding Mexico, exports to other Latin American countries have grown by a whopping 22 percent. This is phenomenal growth considering that several economies have faced fiscal calamity (Argentina), political upheaval (Venezuela and Ecuador), increased drug trafficking (Colombia), and a variety of other disruptive forces. Moreover, trade with Latin America shows no sign of abating. In fact, as Table 1-2 shows, one-fifth of total U.S. exports to the entire world go to Latin America.

Table 1-2 | Total U.S. Export...