![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

FROM DUNCE TO DA VINCI—HOW CREATIVE ARE YOU?

Do you suffer from D.R.I.P.? It stands for a “Dearth of Robust Ideas and Plans.” Do you have a dearth? How many new ideas—for your business or personal life—have you come up with this week? This month? In the past year? Jot down the best of them.

MY REALLY TERRIFIC IDEAS

(last 12 months)

(1) ______________________________________________

(2) ______________________________________________

(3) ______________________________________________

(4) ______________________________________________

(5) ______________________________________________

How many did you come up with? If you listed two or three, you’re an exception. Most people would probably feel blessed to list even one terrific idea. But the good news is, it only takes one.

Henry Ford took just one idea—assembly line production—and built automobiles cheaply enough for the masses to afford them. Putting that one idea to work changed Ford’s life spectacularly. It also, of course, changed the world. Who was the Svengali who first twisted a bit of wire into the shape of a paper clip? Who wrote the most useful cookbook among those sitting on your kitchen shelf? What was the most innovative thing your employer accomplished in the past year? Who thought it up? (Incidentally, the answer is probably not “the engineering group” or “the marketing committee.” In most cases, the truly good idea is conceived by a single individual—or a pair of individuals working as a team.) Whenever even one new idea is put into operation, change happens. And if you are the one who comes up with that idea, the change will bring with it a flood of positive benefits.

Okay, be honest now. How creative are you? Most people have a general idea of how “smart” they are. Somewhere along the line a teacher probably leaked your supposedly confidential IQ score and revealed that you are a 115 or a 127 or maybe even a superstar of 150 or above. But is a high IQ score a sign of high “creativity”? Not necessarily. High creativity thrives on the somewhat oddball ability to see things differently—and then spot new connections in the old stuff. Most new ideas are the result of cross-fertilization between previously unrelated thoughts.

In the mid-1400s, Johannes Gutenberg spent years trying to invent a way to make duplicate copies of documents easily. The monks who painstakingly handprinted parchment sheets one at a time must have seemed awfully inefficient to Gutenberg. So he thought about: (1) the paper rubbings that reproduced pictures etched on stones. He thought about: (2) the metal coin punch used to strike an image on individual coins. And he thought about: (3) the wine screw press that put a slow, steady pressure on a surface. Then one day he put it all together—Eureka!—and came up with a stunning idea. Gutenberg carved each letter of the alphabet on its own little “coin punch.” Next, he arranged a series of the punches to form words and locked them into position with a wooden frame. Finally, he inked his type punches, put a sheet of paper underneath the rig, and applied slow, steady pressure with a wine press. When he unscrewed the press and withdrew the sheet of paper, he was looking at the world’s first printed document. Gutenberg’s “printing press”—with its movable type—was a wondrous machine that revolutionized the way people communicated. Yet it was simply a unique, innovative way of arranging familiar elements.

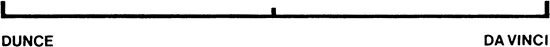

The mind’s ability to jump, cross-fertilize, mix, and blend (as Gutenberg’s mind did) is truly incredible—but those abilities are not measured by a standard IQ test. So let’s invent our own measure of creativity. It’s a simple line graph that will help you visualize your “Creativity Quotient,” or CQ.

At the left of the graph is DUNCE—the dullest person you can conjure up. A DUNCE is someone who, when first asked to boil an egg, can’t find the stove. The DUNCE is a “never ever.” He has never ever had an original thought or idea. He has never ever broken a rule and follows them rigorously his entire life. Lead him to the stove and show him how to boil an egg, and he will never vary the routine by one iota. It is inconceivable to imagine that the true DUNCE, with egg in hand, would ever think of scrambling it.

Now, way over on the right side of the graph is DA VINCI. Leonardo da Vinci gets my vote as the world’s most original and innovative idea-maker to date. Born in Italy during the Renaissance, Leonardo produced paintings, such as his enigmatic La Gioconda (“Mona Lisa”) that rivaled the best of the Old Masters. But his mind stretched much further. He was also a sculptor, an architect, a city planner, a mathematician, a scientist, and a prolific inventor of such amazing things as chain links, a spring-driven car, the parachute, and the helicopter. To entertain the court occasionally, he became a singer and a lute player. And to appease the warlike, he designed concepts for shrapnel bombs, battle tanks, and a crude forerunner of the machine gun.

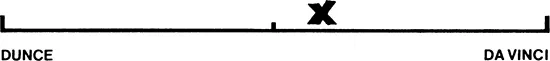

The little mark in the middle of the graph is the halfway point between DUNCE and DA VINCI. It represents a middle-of-the-road average for “creativity.” Now, let’s figure out where you are on that line. There’s no test to take. You simply make a mark where you think you are, relative to all the people you work with, play with, live with, and compete with. Chances are, your mark will fall on the right side of the graph, more DA VINCI than DUNCE.

In other words, you think you have the potential for creative thinking, but you’ve probably never made a concerted effort to improve your CQ. As you begin to focus on the creative process, however, you’ll discover that there are some simple steps you can take that will move your mark further to the right.

Do you want to generate more new ideas, and then—one idea at a time—make them happen? Do you want more of that elusive quality described enviously as “creativity”? Do you truly want to nudge your X toward the far right side of the scale? If you just answered yes, yes, and yes, the first thing you have to do is turn on the creativity you already have, just waiting to be tapped. And before long that D.R.I.P. will become a gusher.

![]()

Chapter 2

LOOSENING UP—A FEELING YOU’LL NEVER FORGET

As you probably know, the left hemisphere of the human brain controls your rational, sequential, linguistic functions. It’s very good at precise logical things like math and science. (Think of the left brain as TIGHT.) The right hemisphere is emotional, visual, intuitive—and imaginative. It is free-spirited and perceptive enough to see both the forest and the trees. (Think of the right brain as LOOSE.) Most people agree that true creativity—the ability to see things differently, or put them together in different ways—originates in the right hemisphere. But first you may have to trick your hidebound left brain into giving your fun-loving right brain more sway.

Wouldn’t it be exciting to break some of those left-brain rules you’ve always lived by—to start to look at things differently? The USSR—of all places—may have a lesson for us. As reported in Fortune magazine, there are now “creative development” seminars for Soviet citizens, an experiment initiated under Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika. Aimed at government officials and factory workers, these seminars include one piece of advice intended to loosen up a hidebound citizen’s view of life: “Don’t get stuck in confining routines. For variety, when you go to your home tonight don’t enter through the door. Instead, try going in through the window.”

The very act of doing something in a totally new way upsets your left brain’s applecart and you suddenly discover the joy of an unexpected viewpoint. You edge back toward that time long ago when your left brain was a blank slate. Think about it. We make our debut on this planet as seven or eight pounds of totally free spirit. At the moment of birth, there are no no’s, no constraints. It is a time of incredible freedom that goes on for several weeks, possibly even several months. But then our parental drill sergeants start to issue orders. They initiate construction of the little boxes we will be asked to live in. More little boxes pile up with a thunderous acceleration as the years go by. There are educational demands, religious codes of conduct, employment obligations, social and legal requirements, the demands of relationships, and so on. Most of us live lives that are tightly confined by an astounding number of boxes. So start by jumping out of a couple of them. Open yourself to the power of new perceptions and ideas—then put them to work to make positive changes in your life. Oliver Wendell Holmes put it this way:

Here are some loosening-up exercises that will stretch your mind and give you a new perspective on old habits and familiar activities. Read the following list of suggestions and pick three or four of them to try. You’ll find that you will experience, or see, familiar things in unfamiliar ways. Your left brain will be grasping to find “logic” in your actions. Your right brain will be having a ball.

(1) Switch your watch to your other wrist for a whole day. (Will anyone else notice? No. Will you notice? Every single time you glance at your nude wrist.)

(2) Try an obscure candy bar you’ve never tasted. Eat just one bite and write a ten-word description of it. (Ever notice how tough it is to describe a taste?)

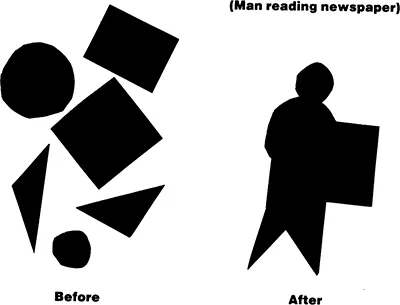

(3) Cut some squares, circles, and triangles out of colored paper and move the pieces around until they make a picture. How many different pictures can you make?

(4) Rearrange your life’s places. Move your bed to another spot. Switch the TV to another position. If you work in an office and your desk faces a door, turn it so it faces a window or a wall. How do these feel? Do any of the new arrangements work better?

(5) Using dabs of glue, build a six-foot tower of empty soda pop cans. Be eclectic in your choice of brands and...