![]()

1

A RESCUE FROM DEMONS

THE VILLAGE OF KARZ sits amid grape fields in the low river valleys southeast of Kandahar, one of the last weak patches of green before the land empties

into miles of flat desert browns. You can get there by the one paved road that runs down from Kandahar, a scorched outpost on the old Asian trade and conquest routes. Most of the people who live in

Karz are sheepherders or peasant farmers. They irrigate their fields from generator-powered wells and dry their green grapes into raisins in mud structures perforated to let the hot wind blow

through. The other business is brickmaking, and from where I stood at the entrance to the village I could see black smoke drifting sideways from the towering sand-colored kilns, adding another

layer of haze to the dusty air. One thing that distinguished Karz from the countless identical mud-hut villages across southern Afghanistan was that it happened to be the ancestral home of the

family of the then Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, the place from which they had taken their name. That was why I was standing exposed on that lonely country road, a foreigner sweating through his

unconvincing Afghan costume of billowy brown blouse and matching pants, on the morning the president’s favorite brother would be buried.

An Afghan army Humvee had parked crosswise in the road, blocking my approach. In case anyone wanted to slip past, Afghan snipers wearing wraparound shades stood on the rooftops of the roadside

shops, muttering into their earpieces. On my way out of Kandahar City, I had seen American soldiers idling in their mine-resistant armored vehicles at various intersections, their Apache

helicopters running slow loops overhead. They would be staying away from the ceremony this morning, in a distant cordon, and I began to think I would miss it, too. The day before, July 12, 2011, I had left my house in Kabul, where I worked as a reporter for The Washington Post, and rushed to the airport when I’d learned that Ahmed

Wali Karzai had been shot to death inside his home by one of his closest lieutenants. To me, he was one of the war’s mythical figures, a short, scowling, anxious man who had, everyone took

for granted, amassed more power and fortune than anyone else across Afghanistan’s south, at the center of America’s war against the Taliban. How he’d made that fortune and

exercised that power was one of the mysteries that none of his American allies could fully explain. Everyone had theories: the CIA payroll, the opium trade, a private security army, a healthy cut

of the logistical billions needed to house and feed and arm the tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers and Marines in outposts across the south. You could find among American soldiers and civilians

those who considered him our country’s best friend or its worst enemy, the only man preventing a Taliban takeover or the reason America was losing the war.

President Hamid Karzai was even more of a puzzle. He was the pacifist commander in chief for the duration of the longest war in the history of the United States. On the spectrum of Afghan

politics, he held liberal, pro-Western beliefs but had become the scourge of America. He was the ascetic in a family of millionaires; the workaholic head of an ineffective government; a profane

lover of poetry with a weeping heart and tactical mind and twitchy left eye. He was constantly sick. He had ridden a miraculous wave of luck and circumstance into the presidential palace after

holding only one government job, a one-year stint a decade earlier as deputy foreign minister that had ended with his arrest, torture, and escape into exile. He was not brave in battle, like

Afghanistan’s other bearded and berobed leaders. He commanded no militia following and had grown up in Kandahar leafing through Time magazine, playing Ping-Pong on

the dining room table, and riding a horse named Almond Blossom.

In the family of seven sons and one daughter from two mothers, the half brothers Hamid and Ahmed Wali had been particularly close. During Hamid’s post–September 11 return to

Afghanistan, Ahmed Wali devoted himself to the logistics of fomenting the Pashtun uprising against the Taliban and helped the CIA set up its operations in Kandahar. Throughout Hamid’s

presidency, Ahmed Wali had been the enforcer of his political agenda in southern Afghanistan. They talked on the phone nearly every day. Ahmed Wali worked to undercut tribal rivals to keep their

Pashtun tribe, the Popalzai, dominant and well funded. He helped the other siblings realize their outlandish dreams, smoothing the road for elder brother Mahmood Karzai to build a

giant gated city in the Kandahar desert, while blocking challengers within the family who burned to steal his mantle as Kandahar’s reigning don. Ahmed Wali put his elder brother Shah Wali, a

shy engineer, to work for him after he couldn’t find a job he wanted in the palace. For years, while other siblings sought their daily comforts in Maryland or Dubai, Ahmed Wali grappled every

day in the death match of Kandahar politics. And in his sudden absence, nobody knew what to expect.

Out on the road to Karz, I felt a throb of energy, thinking about this prospect. Work as a journalist, even in war zones, often numbs into routine. Foot patrols, tea with governors, round-table

briefings, village council meetings. PowerPoint slides, press releases, bar charts, death tolls. The war got explained and narrated and re-created, and you often felt absent from whatever forces

were animating it. Your vantage point was always obscured. You were always racing toward something you had just missed, arriving just as men were hosing down the blood and sweeping up the glass.

Bombings in Kabul roused us from our desks and beds. We would meet at the scene to jot down the particulars—red Corolla, severed head—and chat about parties. Who even read bombing

stories anymore? Kabul City Center. The Finest supermarket. Bakhtar guesthouse. Serena Hotel. Kabul National Military Hospital. ISAF front gate. Indian embassy. Ariana Circle. Microrayon 4.

Jalalabad Road. Lebanese Taverna. The British Council. I used to be surprised by how quickly the vendors set up shop and put out their wares after their market was shredded by explosives, or their

neighbors, friends, or coworkers killed. After some time in Kabul, the question seemed naïve. For Afghans, and for those of us involved in this late stage of the war, bombings had become both

as routine and as unpredictable as a clap of thunder: attacks as natural disasters—an unfortunate run of climate.

There was always a strong element of mindlessness to this deadly weather. We were accustomed to bombings, yes. But we were also accustomed to ignorance, to the acceptance that these crimes would

not be solved, these dramas and plots would not be unraveled, or ever explained. We would never really know whether a certain explosion was the result of the meticulous planning of Mullah Omar, the

Taliban’s one-eyed leader, or a heroin trafficker or Pakistani intelligence or a scorned lover or a thirteen-year-old boy who got nervous and blew himself up two blocks before his intended

target, one he didn’t even know why he’d been sent to bomb. It was easy to speculate and, for those who didn’t have to, even easier not to. The Afghanistan I

experienced was all aftermath and poorly informed interpretation.

What interested me in the Karzais, why I was trying to get to Karz, was the hope that traveling in their world would offer some chance, however slim, at explanation. If anyone understood

Afghanistan’s motives, if anyone knew its causes and effects, I imagined it might be them. They seemed to offer something to hold on to even if that thing wasn’t hope or good faith. I

wanted some relief from misunderstanding. That Wednesday morning in Karz felt promising if only because I was there early, waiting for whatever would come down the road.

What came down the road was a group of men carrying bamboo broomsticks, then a man pushing a wheelbarrow, a guy toting a shovel, and four policemen in mismatched shoes and white cruise-ship

captain’s hats. I wondered if maybe I was, once again, too late. Then a procession of men, twenty abreast and filling the road, came into view. They wore turbans and blazers and sandals and

wristwatches that glinted in the sunlight, row after unsmiling row. The procession swept by and through us and we fell in among them, following the surging crowd through the village until we came

to a grove of eucalyptus trees ringed by a white metal fence topped with arrow-shaped spikes that surrounded the Karzai family cemetery. We entered through the gate.

Across the cemetery grounds, dozens of humble headstones marked the graves of lesser Karzais. In the center stood a small, open-air domed mausoleum, an inner sanctum reserved for family royalty.

The president’s father, Abdul Ahad Karzai, a former parliament member and leader of the Popalzais, was buried here, as was his grandfather, another tribal khan,

Khair Mohammad. That morning, men from the village had used picks and shovels to pierce its marble floor and dig the grave where Ahmed Wali lay in the dirt under a white sheet.

The crowd surged around the open grave. Shouting and jostling, mourners pushed toward it six and seven men deep. Among them were many Popalzais who lived in the area and surrounding villages.

There were also dignitaries who had flown in from Kabul the night before. I recognized cabinet ministers, army generals, and provincial governors, sweating in their suits and uniforms. People were

wailing and crying. Security guards in black bulletproof vests with curly cords tucked behind their ears tried in vain to keep control, screaming and shoving people back from the lip. The sound of

rotor blades rose above the din, and a U.S. military Black Hawk helicopter touched down in a plume of dust. The president had arrived.

Hamid Karzai, looking wan, pushed through the tangle of bodies and stood at the edge of the grave. He wore a simple white tunic and a dark vest. He looked down into the hole and said nothing. I

could see he was crying. For a second the scene seemed to freeze, bodies teetering over the pit, all eyes trained on him.

Then he dropped into the grave. He knelt to kiss his murdered brother, and the crowd closed in over him, breaking like water through a dam. People enveloped him in a tangle of interlocking

limbs. He stayed down there, out of sight under the bodies, for what seemed like minutes, amid the keening moan of the crowd. Then the bodies parted and he rose from the ground, hoisted up and out

of the grave by the men around him. He walked quickly through them, out through the cemetery gate to his waiting convoy, and drove off without saying a word.

A group of men lowered a concrete slab over the corpse and shoveled in dirt. When they had filled the grave, they pressed in two saplings, one at either end, and tied them together with pink

ribbon. Almost everyone had dispersed by the time it was done.

Ahmed Wali’s funeral took place in the middle of Hamid Karzai’s second and last full term, nearly ten years after he moved into the palace in Kabul. The

thirty-three thousand additional troops that President Obama had sent to Afghanistan, pushing the total American commitment to more than one hundred thousand, would begin withdrawing in the next

few months. The headline battles—in the small town of Marja, in Helmand Province, the offensive to retake the Taliban birthplace in Kandahar—had ended inconclusively. The first became

known by General Stanley McChrystal’s evocative phrase: “a bleeding ulcer.” The initial enthusiasm of the second had faded into a stalemate

punctuated by embarrassment when nearly five hundred Taliban fighters burrowed out of Kandahar’s main prison through an underground tunnel. The month of Ahmed Wali’s burial, there were

more than three thousand Taliban attacks across the country.

During the five years I lived in or was visiting Afghanistan, over the course of that second term, 2009 to 2014, the Taliban were largely nameless, faceless adversaries. No one could say for

certain much about Mullah Omar—where he lived, how he spent his time, whether he actively led and guided his troops or whether he was merely a rallying symbol. Hundreds of

news stories about the war quoted Zabiullah Mujahid, the Taliban spokesman, about the day’s events. But the Afghan reporters who made those phone calls—in the Pashto

language—heard several different voices over the years all claiming to be that singular Mujahid. I went to a briefing at U.S. military headquarters once about the Taliban propaganda

machinery—their mobile radio transmissions, their inflated claims of destruction of the infidel cowards—by the “strategic communications” team from the U.S.-led coalition,

known as the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), and was told there were more than a dozen Zabiullahs. For the Americans, the Taliban movement was never about the individual. It was

about the sporadic, anonymous waves of violence, never overwhelming but never ceasing, coming in small ambushes, hit-and-run attacks and assassinations, across farmlands, deserts, and mountains,

much of it far away and out of sight.

In the inability to stop or even greatly alter this insurgency, the fixation for many American soldiers and diplomats fell on those Afghans they could manipulate, including our supposed allies

in government, the Karzai family. For the U.S. military commanders and diplomats in Kabul, Hamid’s failings, and the wider problems represented by his family—corruption, warlordism, a

disregard for democratic institutions—became a parallel but equally intense preoccupation. So it was not so much the combat that defined, for me, the war in Afghanistan, but these political

struggles: to remake an ancient tribal society into a modern democratic country, to constrain the very people the United States endowed with immense power and money, to relate and find common

ground in a culture with deeply different customs and beliefs than those of the American soldiers fighting on its behalf. The Karzais stood at the center of all these struggles, and in their

personal rivalries and political lives I found a way to understand the war and why we could not win it.

The president and his brothers began as symbols of a new Afghanistan: moderate, educated, fluent in East and West—the antithesis of the brutish and backward Taliban regime, which blew up

Buddha statues and banned kids from flying kites. Most of them had spent the bulk of their adult lives in America and had come back to Afghanistan to help rebuild it into the peaceful country they

remembered from childhood. Hamid Karzai was celebrated around the world as a unifier and peacemaker. But by the time of Ahmed Wali’s burial, the Karzai name had become shorthand for

corruption, greed, and a bewildering rage at America. His family had descended into deadly feuds and scrambles for money that Ahmed Wali’s death would intensify. President

Karzai’s relations with U.S. diplomats and soldiers amounted to little but distrust and traded insults. On his next trip to Kandahar, Hamid Karzai, with tears in his eyes, would tell

villagers that Americans were “demons,” adding, “Let’s pray for God to rescue us” from them.

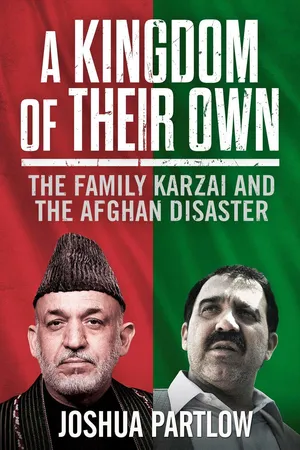

Hamid Karzai standing above the grave of his half brother Ahmed Wali Karzai on the day of his burial, July 13, 2011, in the family cemetery in

Karz

![]()

2

ANY PATH WILL LEAD YOU THERE

THREE DAYS BEFORE Afghan voters would go to the polls to elect a new president, Timothy Carney sent a worried note to U.S. ambassador Karl Eikenberry. The subject line read, “Fraud Marker for Karzai.”

Carney had spent his diplomatic career navigating far-off conflicts and despotic regimes: in Saigon during the Tet offensive, Phnom Penh during the Khmer Rouge era, Port-au-Prince during the American invasion, two tours in Iraq. He hunted big game; he wore a boater. In a crisis, he felt at ease. His old State Department colleague Richard Holbrooke had called on him for one more run: fly to Kabul to oversee what had become the most important political test of the Afghan war, the election in which Hamid Karzai was running for a second term.

Karzai became Afghanistan’s leader three months after September 11, and for a few years he was held up as an exceptional statesman. He had corralled a coalition of ethnic rivals and kept them from warring with each other. He’d created a government out of mostly nothing, planted democratic seeds in a country where dynasty or brute force had normally prevailed. He was an eager partner in whatever designs American officials had on his country, the suave and modern face of a backward nation. None of that had been enough to halt his steadily slipping authority. By the summer of 2009, the Taliban’s fighters were running a parallel government that ruled rural villages and towns across the Pashtun provinces in the south and east. In the months prior, suicide attackers had detonated car bombs outside American military bases in Kabul, laid siege to the Justice Ministry building, and fired rockets at the U.S. embassy. American soldiers were dying at a rate of nearly two per day, higher than in any month in the eight previous years of fighting. “I won’t say that things are all on the right track,” General David McKiernan had noted six months earlier, just before he was ousted from command in Kabul. “So the idea that it might get worse before it gets better is certainly a possibility.”

In his first election, in 2004, Karzai had run without any serious challenger and with the full support of the United States, but the shine ha...