![]()

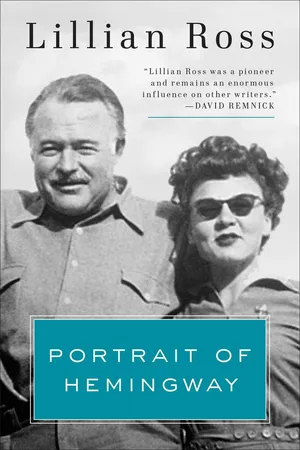

ERNEST HEMINGWAY, who may well be the greatest American novelist and short-story writer of our day, rarely comes to New York. For many years, he has spent most of his time on a farm, the Finca Vigia, nine miles outside Havana, with his wife, a domestic staff of nine, fifty-two cats, sixteen dogs, a couple of hundred pigeons, and three cows. When he does come to New York, it is only because he has to pass through it on his way somewhere else. Late in 1949, on his way to Europe, he stopped in New York for a few days. I had written to him asking if I might see him when he came to town, and he had sent me a typewritten letter saying that would be fine and suggesting that I meet his plane at the airport. “I don’t want to see anybody I don’t like, nor have publicity, nor be tied up all the time,” he went on. “Want to go to the Bronx Zoo, Metropolitan Museum, Museum of Modern Art, ditto of Natural History, and see a fight. Want to see the good Breughel at the Met, the one, no two, fine Goyas and Mr. El Greco’s Toledo. Don’t want to go to Toots Shor’s. Am going to try to get into town and out without having to shoot my mouth off. I want to give the joints a miss. Not seeing news people is not a pose. It is only to have time to see your friends.” In pencil, he added, “Time is the least thing we have of.”

Time did not seem to be pressing Hemingway the day he flew in from Havana. He was to arrive at Idlewild late in the afternoon, and I went out to meet him. His plane had landed by the time I got there, and I found him standing at a gate waiting for his luggage and for his wife, who had gone to attend to it. He had one arm around a scuffed, dilapidated briefcase pasted up with travel stickers. He had the other around a wiry little man whose forehead was covered with enormous beads of perspiration. Hemingway had on a red plaid wool shirt, a figured wool necktie, a tan wool sweater-vest, a brown tweed jacket tight across the back and with sleeves too short for his arms, gray flannel slacks, Argyle socks, and loafers, and he looked bearish, cordial, and constricted. His hair, which was very long in back, was gray, except at the temples, where it was white; his mustache was white, and he had a ragged, half-inch, full white beard. There was a bump about the size of a walnut over his left eye. He had on steel-rimmed spectacles, with a piece of paper under the nosepiece. He was in no hurry to get into Manhattan. He crooked the arm around the briefcase into a tight hug and said that inside was the unfinished manuscript of his new book, “Across the River and Into the Trees.” He crooked the arm around the wiry little man into a tight hug and said the man had been his seat companion on the flight. The man’s name, as I got it in a mumbled introduction, was Myers, and he was returning from a business trip to Cuba. Myers made a slight attempt to dislodge himself from the embrace, but Hemingway held on to him affectionately.

“He read book all way up on plane,” Hemingway said. He spoke with a perceptible Midwestern accent, despite the Indian talk. “He liked book, I think,” he added, giving Myers a little shake and beaming down at him.

“Whew!” said Myers.

“Book too much for him,” Hemingway said. “Book start slow, then increase in pace till it becomes impossible to stand. I bring emotion up to where you can’t stand it, then we level off, so we won’t have to provide oxygen tents for the readers. Book is like engine. We have to slack off gradually.”

“Whew!” said Myers.

Hemingway released him. “Not trying for no-hit game in book,” he said. “Going to win maybe twelve to nothing or maybe twelve to eleven.”

Myers looked puzzled.

“She’s better book than ‘Farewell,’ ” Hemingway said. “I think this is best one, but you are always prejudiced, I guess. Especially if you want to be champion.” He shook Myers’ hand. “Thanks for reading book,” he said.

“Pleasure,” Myers said, and walked off unsteadily.

Hemingway watched him go, and then turned to me. “After you finish a book, you know, you’re dead,” he said moodily. “But no one knows you’re dead. All they see is the irresponsibility that comes in after the terrible responsibility of writing.” He said he felt tired but was in good shape physically; he had brought his weight down to two hundred and eight, and his blood pressure was down, too. He had considerable rewriting to do on his book, and he was determined to keep at it until he was absolutely satisfied. “They can’t yank novelist like they can pitcher,” he said. “Novelist has to go the full nine, even if it kills him.”

We were joined by Hemingway’s wife, Mary, a small, energetic, cheerful woman with close-cropped blond hair, who was wearing a long, belted mink coat. A porter pushing a cart heaped with luggage followed her. “Papa, everything is here,” she said to Hemingway. “Now we ought to get going, Papa.” He assumed the air of a man who is not going to be rushed. Slowly, he counted the pieces of luggage. There were fourteen, half of them, Mrs. Hemingway told me, extra-large Valpaks designed by her husband and bearing their hierro, also designed by him. When Hemingway had finished counting, his wife suggested that he tell the porter where to put the luggage. Hemingway told the porter to stay right there and watch it; then he turned to his wife and said, “Let’s not crowd, honey. Order of the day is to have a drink first.”

We went into the airport cocktail lounge and stood at the bar. Hemingway put his briefcase down on a chromium stool and pulled the stool close to him. He ordered bourbon and water. Mrs. Hemingway said she would have the same, and I ordered a cup of coffee. Hemingway told the bartender to bring double bourbons. He waited for the drinks with impatience, holding on to the bar with both hands and humming an unrecognizable tune. Mrs. Hemingway said she hoped it wouldn’t be dark by the time they got to New York. Hemingway said it wouldn’t make any difference to him, because New York was a rough town, a phony town, a town that was the same in the dark as it was in the light, and he was not exactly overjoyed to be going there anyway. What he was looking forward to, he said, was Venice. “Where I like it is out West in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, and I like Cuba and Paris and around Venice,” he said. “Westport gives me the horrors.” Mrs. Hemingway lit a cigarette and handed me the pack. I passed it along to him, but he said he didn’t smoke. Smoking ruined his sense of smell, a sense he found completely indispensable for hunting. “Cigarettes smell so awful to you when you have a nose that can truly smell,” he said, and laughed, hunching his shoulders and raising the back of his fist to his face, as though he expected somebody to hit him. Then he enumerated elk, deer, possum, and coon as some of the things he could truly smell.

The bartender brought the drinks. Hemingway took several large swallows and said he got along fine with animals, sometimes better than with human beings. In Montana, once, he lived with a bear, and the bear slept with him, got drunk with him, and was a close friend. He asked me whether there were still bears at the Bronx Zoo, and I said I didn’t know but I was pretty sure there were bears at the Central Park Zoo. “I always used to go to the Bronx Zoo with Granny Rice,” he said. “I love to go to the zoo. But not on Sunday. I don’t like to see the people making fun of the animals, when it should be the other way around.” Mrs. Hemingway took a small notebook out of her purse and opened it; she told me she had made a list of chores she and her husband had to do before their boat sailed. They included buying a hot-water-bottle cover, an elementary Italian grammar, a short history of Italy, and, for Hemingway, four woollen undershirts, four pairs of cotton underpants, two pairs of woollen underpants, bedroom slippers, a belt, and a coat. “Papa has never had a coat,” she said. “We’ve got to buy Papa a coat.” Hemingway grunted and leaned against the bar. “A nice, rainproof coat,” Mrs. Hemingway said. “And he’s got to get his glasses fixed. He needs some good, soft padding for the nosepiece. It cuts him up brutally. He’s had that same piece of paper under the nose-piece for weeks. When he really wants to get cleaned up, he changes the paper.” Hemingway grunted again.

The bartender came up, and Hemingway asked him to bring another round of drinks. Then he said, “First thing we do, Mary, as soon as we hit hotel, is call up the Kraut.” “The Kraut,” he told me, with that same fist-to-the-face laugh, was his affectionate term for Marlene Dietrich, an old friend, and was part of a large vocabulary of special code terms and speech mannerisms indigenous to the Finca Vigia. “We have a lot of fun talking a sort of joke language,” he said.

“First we call Marlene, and then we order caviar and champagne, Papa,” Mrs. Hemingway said. “I’ve been waiting months for that caviar and champagne.”

“The Kraut, caviar, and champagne,” Hemingway said slowly, as though he were memorizing a difficult set of military orders. He finished his drink and gave the bartender a repeat nod, and then he turned to me. “You want to go with me to buy coat?” he asked.

“Buy coat and get glasses fixed,” Mrs. Hemingway said.

I said I would be happy to help him do both, and then I reminded him that he had said he wanted to see a fight. The only fight that week, I had learned from a friend who knows all about fights, was at the St. Nicholas Arena that night. I said that my friend had four tickets and would like to take all of us. Hemingway wanted to know who was fighting. When I told him, he said they were bums. Bums, Mrs. Hemingway repeated, and added that they had better fighters in Cuba. Hemingway gave me a long, reproachful look. “Daughter, you’ve got to learn that a bad fight is worse than no fight,” he said. We would all go to a fight when he got back from Europe, he said, because it was absolutely necessary to go to several good fights a year. “If you quit going for too long a time, then you never go near them,” he said. “That would be very dangerous.” He was interrupted by a brief fit of coughing. “Finally,” he concluded, “you end up in one room and won’t move.”

After dallying at the bar a while longer, the Hemingways asked me to go with them to their hotel. Hemingway ordered the luggage loaded into a taxi, and the three of us got into another. It was dark now. As we drove along the boulevard, Hemingway watched the road carefully. Mrs. Hemingway told me that he always watched the road, usually from the front seat. It was a habit he had got into during the First World War. I asked them what they planned to do in Europe. They said they were going to stay a week or so in Paris and then drive to Venice.

“I love to go back to Paris,” Hemingway said, his eyes still fixed on the road. “Am going in the back door and have no interviews and no publicity and never get a haircut, like in the old days. Want to go to cafés where I know no one but one waiter and his replacement, see all the new pictures and the old ones, go to the bike races and the fights, and see the new riders and fighters. Find good, cheap restaurants where you can keep your own napkin. Walk all over the town and see where we made our mistakes and where we had our few bright ideas. And learn the form and try and pick winners in the blue, smoky afternoons, and then go out the next day to play them at Auteuil and Enghien.”

“Papa is a good handicapper,” Mrs. Heming...