eBook - ePub

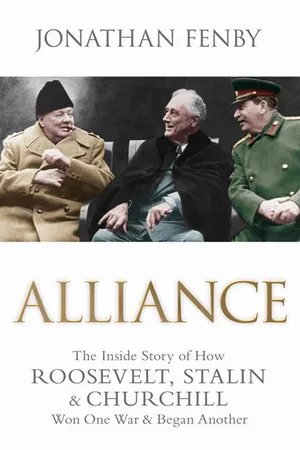

Alliance

The Inside Story of How Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill Won One War and Began Another

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alliance

The Inside Story of How Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill Won One War and Began Another

About this book

The history of the Second World War is usually told through its decisive battles and campaigns. But behind the front lines, behind even the command centres of Allied generals and military planners, a different level of strategic thinking was going on. Throughout the war the 'Big Three' -- Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin -- met in various permutations and locations to thrash out ways to defeat Nazi Germany -- and, just as importantly, to decide the way Europe would look after the war. This was the political rather than military struggle: a battle of wills and diplomacy between three men with vastly differing backgrounds, characters -- and agendas.

Focusing on the riveting interplay between these three extraordinary personalities, Jonathan Fenby re-creates the major Allied conferences including Casablanca, Potsdam and Yalta to show exactly who bullied whom, who was really in control, and how the key decisions were taken. With his customary flair for narrative, character and telling detail, Fenby's account reveals what really went on in those smoke-filled rooms and shows how "jaw-jaw" as well as "war-war" led to Hitler's defeat and the shape of the post-war world.

Focusing on the riveting interplay between these three extraordinary personalities, Jonathan Fenby re-creates the major Allied conferences including Casablanca, Potsdam and Yalta to show exactly who bullied whom, who was really in control, and how the key decisions were taken. With his customary flair for narrative, character and telling detail, Fenby's account reveals what really went on in those smoke-filled rooms and shows how "jaw-jaw" as well as "war-war" led to Hitler's defeat and the shape of the post-war world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alliance by Jonathan Fenby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

★ ★ ★

Buffalo, Bear and Donkey

‘The structure of world peace . . . must be a peace which rests on the cooperative effort of the whole world.’

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT1

THE THREE MEN WHO WON the biggest conflict in human history and shaped the globe for half a century thereafter knew from the start that they could not afford to fail. Once total war had been forced on them by the Axis powers, no compromise was possible. Victory over ‘Hitler’s gang’ in Europe and the Imperial Way in Asia had to be total. ‘If they want a war of extermination, they shall have one,’ said Stalin.2

The conflict was more wide-ranging than the First World War, stretching across the Atlantic and Pacific, through Europe and Asia, from the Arctic to North Africa. More than 50 million people died in 2,174 days of fighting between 1939 and 1945 – many others perished earlier in Japan’s invasion of China that began in 1931. Mass killing of civilians was taken for granted on all sides – half the 36 million people who died in Europe were non-combatants, and Chinese civilian casualties amounted to many millions. Though there was bitter and bloody hand-to-hand fighting, death and destruction was often inflicted by men who did not see those they killed from the air or by artillery. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were logical extensions of the London Blitz. As well as the cost in human lives, the conflict brought enormous material destruction; North America escaped damage but much of Germany and Japan was levelled while a quarter of the Soviet Union’s capital assets were destroyed.

Old continuities were broken for ever as two very different powers with competing philosophies came to dominate the globe, and Britain found itself on a path of decline in the twilight of European empires. Big government, already installed in the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik Revolution, became a fact of life in the other two Allied nations. In America, wartime spending enabled recovery from the Great Depression while Roosevelt crafted the imperial presidency; as Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson noted, the strengthening of the executive was inevitable because ‘the President is the only officer who represents the whole nation.’3

Mass mobilisation, mechanisation, state power and technology were exerted on a massive scale in all three Allied countries. Huge industrial programmes churned out tanks, guns, warships and planes – 50,000 people worked on the biggest single American project, the B-29 Superfortress, which cost a million dollars apiece. Though Britain had rebuilt its economy after the Great Slump, the draining of its resources once the conflict became global would show just how enormous the strain of total war was. Generals managed the deployment of unprecedented forces across the globe. As the historian Eric Hobsbawm notes, it ‘was the largest enterprise hitherto known to man.’4 From the conflict came the United Nations, the Bretton Woods financial system, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and a host of other institutions. The struggle for supremacy produced great technological leaps, whether it was the atom bomb, or the work done by code breakers that spurred on the computer.

Social and democratic conditions, including the employment of women, were altered for ever in some nations. Despite the mass murders by Stalin and Mao, which were greater numerically, Hitler’s genocide of the Jews left the century with its most powerful symbol of man’s inhumanity to man, and led to the creation of the state of Israel. Japan’s sweeping victories in 1941–2 fatally undermined the status of the colonial powers in Asia while the trauma of the third German–French war acted as a powerful catalyst for the European Union.

To a far greater extent than in the 1914–18 conflict, the Second World War was a personal struggle between towering figures – Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, and Hitler, with a supporting cast that included Benito Mussolini, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, General Tojo and Emperor Hirohito, Charles de Gaulle and European governments-in-exile in London. These men had a vital influence, not just on the course of the war but on the world which emerged from it. There was a constant stream of correspondence between the White House and Downing Street, and, to a lesser extent, with the Kremlin. In contrast with the previous conflict, during which European governments changed during the fighting, Stalin and the Democrats ruled throughout the war and Churchill was Prime Minister from May 1940 to the late summer of 1945.

Though Churchill liked to draw a parallel with the coalition led against France by his ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, the association of powers was hardly a classic alliance. The geometry of its meetings was variable. Roosevelt and Churchill had eleven bilateral conferences. Churchill crossed the Atlantic six times and went twice to Moscow. Roosevelt and Stalin never visited either of the other Allied nations. The three leaders gathered as a group only twice – at Teheran, close to the Soviet southern border, and then at Yalta in the Crimea, both locations chosen for the convenience of Stalin who hated flying.

American and British troops never fought in any major fashion alongside the Red Army. While the Western Allies waged a two-hemisphere war for three and a half years, Stalin maintained a non-aggression pact with Tokyo until the summer of 1945 to ward off the threat of Japan opening a second front in Siberia. Nor was there any meaningful joint staff planning between the Western Allies and Moscow. The Kremlin was extremely parsimonious with information, and suspicious of the West – Stalin thought warnings of Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 were a plot to embroil him in war with Berlin. As the conflict went on, one of his main sources was the Soviet spy apparatus in London and Washington.5

Though Washington and London began detailed military discussions well before the United States went to war, meetings of the Combined Chiefs of Staff were marked by fundamental strategic differences. While the US Chiefs wanted a single hammer blow against the Germans in Northern France, the British favoured an indirect approach against the ‘soft underbelly’ of North Africa and Southern Europe. Arguments between the British and the American Chiefs became so violent at times that junior officers had to be asked to leave the room so as not to witness the verbal brawls. China was a particular source of discord. Roosevelt counted on it becoming one of the four post-war global policemen, but Churchill had no time for a country he dismissed as ‘four hundred million pigtails’, which could only divert much-needed aid from Britain – and he was sure Stalin shared his distaste for ‘all this rot about China as a great power’.6

During 120 days of meetings Roosevelt and Churchill developed genuinely warm feelings for one another – if the President ever had genuinely warm feelings for anybody. Before Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt had manoeuvred his way towards giving aid to Britain while America was still technically neutral, seeing the island as a first line of defence. After Pearl Harbor, the Western alliance grew in scope and depth, giving Churchill hope for a post-war partnership of English-speaking peoples that would sustain his nation. But, by the summer of 1943, Roosevelt was seeking bilateral contacts with Stalin, specifically designed to cut out the British.7

This was symptomatic of an alliance which was far more complex and contradictory than it appeared, particularly from the gloss put on it by Churchill in his memoirs. The differences between the policies of the three countries was inescapable. While Washington refused to contemplate any territorial deals as the war was going on, Stalin had set out his stall at the end of 1941, with a demand for a deep security zone in which governments would follow Moscow’s bidding. Three years later, Churchill proposed a mathematical division of interests in eastern and central Europe between Britain and the USSR.

Roosevelt wanted an end to colonies; Churchill declared that he had not been appointed to oversee the liquidation of the British Empire. Roosevelt pressed the Prime Minister to talk to Indian nationalists; at one point Churchill threatened to resign if the President did not let up. Washington linked the spread of democracy with free trade on American lines; the British clung to the preferential system of their imperial domain. The interpretation of high-sounding references to democracy and self-determination in summit statements were so far apart that discussion was usually pointless. As the war progressed, Churchill became increasingly concerned about Soviet power, especially since Roosevelt proposed to withdraw US troops from Europe two years after victory. But the American was confident of being able to handle Stalin, and foresaw the day when the US and Soviet systems would converge as accommodation on his part was met by accommodation from Moscow and a new world was born to parallel the New Deal at home.8

Above all, there was never any question in Roosevelt’s mind of America confronting the USSR militarily. Always the acute domestic politician, he knew that, having won one war, the United States would not be in a mood to fight another for far-away countries. He had to present a rosy picture of the future to voters and looked to a new period in world history in which the United States, working through a global body, would be able to solve differences between the others because ‘we’re big, and we’re strong, and we’re self-sufficient’, as Elliott recorded his father saying. ‘The United States will have to lead. Lead and use our good offices always to conciliate . . . America is the only great power that can make peace in the world stick.’9

When their alliance came into being Churchill was sixty-seven, Stalin sixty-two and Roosevelt fifty-nine. All were men of long experience. Churchill first entered government in London in 1905, and went on to hold a string of senior posts before going into the political wilderness in the 1930s. Roosevelt had been Under Secretary for the Navy during the First World War; he had then served as Governor of New York and run as a vice-presidential candidate before winning the White House in 1932. Stalin’s revolutionary career stretched back to the early part of the century, after which he had clawed his way to the top of the Soviet system, besting his rival Leon Trotsky, and consolidating his power with the great purges of the 1930s.

None of the three was physically imposing. Churchill and Stalin were short and stout. Despite his leonine head and erect bearing, Roosevelt was confined to a wheelchair by the polio he suffered in 1921, though his insistence on standing to deliver speeches and the discretion of the media meant that most Americans had no idea how badly he had been affected. But they became three of the greatest figures on earth, Churchill with V-signs and cigars, Roosevelt with his jaunty air, Stalin all implacable resolve. As believers in the ‘great men theory’ of history, all were masters at making themselves legends in their own lifetimes.

While economic and industrial strength were essential for victory, and two of them had to take account of their electorates, this was a time when the decisions of a tiny group of individuals made all the difference. The centre of power was wherever they were. As President, Roosevelt was Commander-in-Chief. After the German attack, Stalin became Commissar of Defence and Supreme Commander of Soviet Forces as well as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars. Churchill insisted on being Minister of Defence as well as Prime Minister.

They were all adroit users of the media, knowing the importance of their personalities, and their relationship with their countries. Despite having a few trusted cronies, they were solitary figures. Roosevelt had a close confidant in Harry Hopkins, and worked through Averell Harriman, the multi-millionaire envoy to London and Moscow. Churchill had the mercurial Canadian imperialist Lord Beaverbrook, and Stalin could count on Molotov, his right-hand man in the purges and the mass repression of the peasantry. But, though Churchill recognised the authority of the War Cabinet, none of the three was able to share the enormous pressure.

Stalin treated ambassadors as lackeys. Personal summits and 1,700 written messages between Churchill and Roosevelt made envoys largely redundant. The President, who had always operated through his kitchen cabinet, took his Secretary of State to only one wartime conference, and told Churchill he could ‘handle Stalin better than either your Foreign Office or my State Department. Stalin . . . he thinks he likes me better, and I hope he will continue to do so.’ If he could dine with Stalin once a week, Churchill remarked in 1944, ‘there would be no trouble at all.’10

The first of the Big Three to be at war with Hitler was the most outgoing and emotional of the trio, though he could show subtle skills in alliance politics. While making much of having had an American mother, the aristocratic Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was a pure product of British tradition; he was, as has been said, half American but all British. His belief in the importance of the Empire and the genius of the Anglo-Saxon people was unrestrained – at a lunch in Washington in 1943, he told Vice President Henry Wallace simply: ‘We are superior.’11

It is a commonplace to say that, had the war not brought Churchill to Downing Street in May 1940, he would have gone down in history as a political shooting star which had crashed to earth. What was extraordinary was how, having achieved the prime ministership, and despite his vagaries, he got so many things right. Aspects of his wartime performance have come in for robust criticism, but he usually had no choice, as in pursuing the relationship with the United States. Nor can his country’s post-war global decline be laid at his door, while the notion that Britain could have withdrawn from the war and somehow preserved its imperial position is, at best, a fantasy that takes no account of the realities of the time.

Churchill’s weakness was that he had little interest in social and economic matters. Invaluable as his personality was in rallying his country with defiant optimism in 1940, his traditional mindset consigned him to try to deny the looming future. In the words of the broadcaster Edward Murrow he ‘mobilised the English language and sent it into battle’, but, with it, went an anachronistic approach that was profoundly out of tune with the changes the war was bringing. He was, as he himself said, ‘a child of the Victorian era’, not a man for the new world after victory.12

In pursuit of his mission, he was brave to the point of recklessness, as if convinced that he was indestructible now that he had met his moment of destiny. His bodyguard reckoned that he had twenty brushes with death during his life including assassination attempts by an Indian nationalist, a German sniper team and a bomb-planting group of Greek Communists. During the war, he made hazardous flights over thousands of miles, and voyages across seas harbouring German submarines. On one occasion, flying to Moscow in a converted bomber, he dozed with a lighted cigar in his hand while oxygen hissed out round him. In London, he climbed to the roof in Whitehall to watch the Blitz, and, in 1944, it took a royal veto to prevent him witnessing the D-Day landing from a warship off France. ‘There have been few cases in history where the courage of one man has been so important to the future of the world,’ wrote his faithful military aide ‘Pug’ Ismay.13

Churchill was, as he put it himself, ‘a war person’. His wife said she never thought of the time after the conflict because ‘I think Winston will die when it is over.’ He lived for action, a restless, constant font of invention, pushing subordinates to the limit as he fired off notes on everything from grand strategy to prison conditions. He would never give up. ‘KBO’ – Keep Buggering On – was his watchword. He had a hundred ideas a day, ‘and about four of them are good’, Roosevelt remarked. His obsessions and refusal to delegate drove those around him to distraction. His manner could become overbearing – in the summer of 1941, his wife warned him that a devoted member of his entourage had told her he risked being ‘generally disliked by colleagues and subordinates’. She, too, had noticed that – ‘you are not so kind as you used to be’.14

But nobody doubted that he was invaluable to the war effort. ‘Energy, rather than wisdom, practical judgment or vision, was his supreme qualification,’ recalled Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee. Throughout, he remained respectful of parliamentary democracy. He was ‘able to impose his will upon his countrymen, and enjoy a Periclean reign, precisely because he appeared to them larger and nobler than life and lifted them to an abnormal height in a moment of crisis,’ judged the philosopher Isaiah Berlin. ‘It was Churchill’s unique and unforgettable achievement that he created this necessary illusion within the framework of a free system without destroying it or even twisting it.’15

‘I have known finer and greater characters, wiser philosophers, more understanding personalities, but no greater man,’ Dwight Eisenhower wrote. Still, the conflicting emotions he aroused were well summed up in the diary of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Alan Brooke (ennobled as Lord Alanbrooke), who found the Prime Minister a ‘public menace at playing at strategy’, but also ‘quite the most wonderful man I have ever met’. The world, the general a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Also by Jonathan Fenby

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 Buffalo, Bear and Donkey

- 2 The First Summit

- 3 Uncle Joe

- 4 World War

- 5 Four Men Talking

- 6 Undecided

- 7 The Commissar Calls

- 8 Torch Song

- 9 Midnight in Moscow

- 10 As Time Goes By

- 11 Stormy Weather

- 12 Russian Overture

- 13 Pyramid

- 14 Over the Rainbow

- 15 Ill Wind

- 16 Triumph and Tragedy

- 17 The Plan

- 18 Percentage Points

- 19 Red Blues

- 20 Yalta

- 21 Death at the Springs

- 22 Journey’s End

- Source Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- List of Illustrations