- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this unprecedented history of a scientific revolution, award-winning author and journalist Carl Zimmer tells the definitive story of the dawn of the age of the brain and modern consciousness. Told here for the first time, the dramatic tale of how the secrets of the brain were discovered in seventeenth-century England unfolds against a turbulent backdrop of civil war, the Great Fire of London, and plague. At the beginning of that chaotic century, no one knew how the brain worked or even what it looked like intact. But by the century's close, even the most common conceptions and dominant philosophies had been completely overturned, supplanted by a radical new vision of man, God, and the universe.

Presiding over the rise of this new scientific paradigm was the founder of modern neurology, Thomas Willis, a fascinating, sympathetic, even heroic figure at the center of an extraordinary group of scientists and philosophers known as the Oxford circle. Chronicled here in vivid detail are their groundbreaking revelations and the often gory experiments that first enshrined the brain as the physical seat of intelligence -- and the seat of the human soul. Soul Made Flesh conveys a contagious appreciation for the brain, its structure, and its many marvelous functions, and the implications for human identity, mind, and morality.

Presiding over the rise of this new scientific paradigm was the founder of modern neurology, Thomas Willis, a fascinating, sympathetic, even heroic figure at the center of an extraordinary group of scientists and philosophers known as the Oxford circle. Chronicled here in vivid detail are their groundbreaking revelations and the often gory experiments that first enshrined the brain as the physical seat of intelligence -- and the seat of the human soul. Soul Made Flesh conveys a contagious appreciation for the brain, its structure, and its many marvelous functions, and the implications for human identity, mind, and morality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Soul Made Flesh by Carl Zimmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

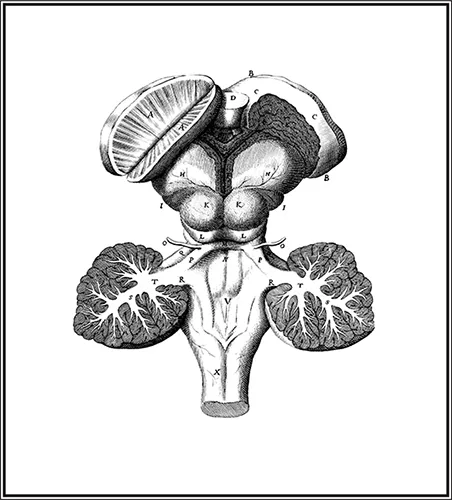

A SHEEP’S BRAIN STEM, FROM THE ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN AND NERVES.

Hearts and Minds, Livers and Stomachs

Thomas Willis was not the first person to take the brain out of its skull. The oldest records of the procedure come from ancient Egypt, four thousand years ago. The Egyptian priests who performed it did not hold up the brain and praise its power, however. Instead, they snaked a hook up the nose of the cadaver, broke through the eggshell-thin ethmoid bone, fished out the brain shred by shred until the skull was empty, and then packed the empty space with cloth.

The priests disposed of the brain while preparing the dead for the journey into the afterlife. The heart, by contrast, stayed in the body, because it was considered the center of the person’s being and intelligence. Without it, no one could enter the afterlife. The jackal-headed god, Anubis, would place the deceased’s heart in a scale, balancing it against a feather. The ibis-headed god, Thoth, would then ask the heart forty questions about the life of its owner. If the heart proved to be heavy with guilt, the deceased would be fed to the Devourer. If the heart was free of sin, the deceased would go to heaven.

It is difficult today to understand how the brain could be so dismissed, but throughout ancient times many people thought it unimportant. Others prized the brain but saw it not as a network of cells that produces language, consciousness, and emotions. They saw it as a shell of pulsing phlegm encasing empty chambers which whistled with the movement of spirits passing through. These two conceptions were powerful enough to guide Western thinking for thousands of years.

Some of the earliest philosophers of ancient Greece followed the Egyptian tradition. Empedocles described the soul as the thing that thinks, feels pleasure and pain, and gives the living body its warmth. At death, it leaves the body and searches for another home in a fish or a bird or even a bush; during its time in the human body, it resides around the heart.

But around 500 B.C., the Greek philosopher Alcmaeon lifted his gaze from the heart to the head, declaring that “all the senses are connected to the brain.” Those words were a milestone in the history of science, but twenty-five hundred years later it’s easy to misinterpret them. To begin with, Alcmaeon and his followers didn’t even know that nerves existed. Few physicians had even seen these pale threads running through the body, because Greeks in general were reluctant to cut open cadavers. They were too worried that the souls of the dissected would not find rest in the afterlife until they got a proper burial. Alcmaeon reportedly cut the eye out of a dead animal’s head and saw channels penetrating the skull. Like other ancient Greeks, he probably pictured channels in the body filled with spirits (or pneumata). These spirits were made of air, which was one of the four elements of the cosmos, along with fire, earth, and water. Each time a person took in a breath, these spirits were believed to flow into the nose, through the recesses of the brain, and into the body.

Alcmaeon’s ideas helped shape early Greek medicine. In addition to spirits, physicians also came to believe that the body was composed of combinations of the elements known as humors. These four fluids—yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm—each had its own qualities of moistness, dryness, heat, cold, and so on. The physician Hippocrates taught that good health was a matter of balancing the humors. If the brain, which was made of moist phlegm, became too moist, epilepsy might follow. If the phlegm moved from the brain to other parts of the body, tuberculosis or other diseases might strike.

Alcmaeon attracted a following not only among physicians but among philosophers as well. The most important of these was Plato, who gave the brain a central place in the cosmos. In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato described the cosmos as a living thing created by a divine craftsman, complete with its own immortal soul. The divine craftsman gave lesser gods the task of creating human beings, which they designed as the cosmos in miniature: with an immortal soul cloaked in a mortal body welded from the four elements. The gods began their work by creating the head, which they made spherical, like the cosmos. The divine seed was planted in the brain, where it could sense the world through the eyes and ears and then reason about it. This reasoning was the divine mission of the human soul; it would be able to reproduce the harmony and beauty of the cosmos in its own thoughts.

Into the rest of the body the gods inserted souls “of another nature,” as Plato called them. In the guts dwelled “the part of the soul which desires meats and drinks and the other things of which it has need by reason of the bodily nature.” This so-called vegetative soul was responsible for the body’s growth and nutrition and also for its lower passions—its lusts, desires, and greed. To cage this wild beast, the gods built a wall—the diaphragm—separating it from a superior soul, which Plato located in the heart. The vital soul “is endowed with courage and passion and loves contention,” Plato wrote. Along with the blood, the vital soul’s passions flowed out of the heart, exciting the body into action. To keep these lower souls from polluting the immortal soul in the head, the gods created another barrier in the form of the neck.

In Timaeus Plato built a spiritual anatomy with the brain at its apex. It would influence Western thought through the Renaissance, yet it was not powerful enough to bring the heart-centered school of Plato’s own age to an end. In fact, Plato’s most celebrated student, Aristotle, rejected the head and put the heart at the core of his philosophy.

For Aristotle, the brain did not square with his conception of the soul. In his philosophy, every object has a form, which can change as the matter that makes it up changes. A house emerges when stones are combined into a certain form, and its form disappears when the stones are taken apart. There is no one pillar or capstone in which the house resides—its form is everywhere in the house and nowhere in particular. The soul, Aristotle reasoned, is the form of living things. It therefore encompasses everything that a living creature does to stay alive. And since different organisms have different ways of life, they must have different souls, Aristotle concluded, each with its own set of faculties or powers.

To classify souls, Aristotle became the world’s first biologist. He dissected everything from sea urchins to elephants, and while he didn’t break the taboo on human dissections, he probably dissected stillborn babies. Aristotle tracked endless details of natural history, noting which species were warm-blooded and which were cold, which cared for their young and which abandoned their eggs. He found that he could classify species according to the faculties of their souls, ranging them on a ladder from low to high. At the bottom Aristotle put plants, because they had only vegetative souls that did nothing more than let the plants grow, heal themselves, and reproduce. Animals were placed higher than plants, because their souls had sensitive faculties as well: animals can see, hear, taste, and feel; and they can swim, fly, or slither. Humans stood alone at the apex of the natural world, with a rational soul equipped with faculties including reason and will—what we would call a mind.

Like the form of a house, Aristotle’s rational soul was both nowhere and everywhere in the human body. Yet Aristotle also believed that specific parts of the body carry out its faculties. He scoffed at the idea that the brain could be such a place, since he saw from his dissections that many animals had no visible brain at all but still could perceive the world and give rise to actions. The brain itself could not have looked very impressive to Aristotle. Without freezers or formaldehyde to halt its decay, a brain quickly takes on the look and feel of custard—hardly the stuff of reason and will.

The heart, on the other hand, seemed to him to be a far more logical place for the rational soul’s faculties. It is at the center of the body, and it was the first organ that Aristotle could see taking shape in the embryo. Greeks believed that the heart supplies life-giving heat to the body, and Aristotle saw a connection between heat and intelligence. Just as animals had more or less soul, they had more or less heat, mammals being warmer than birds or fish, and humans—he believed—the warmest of all. Unaware of the nerves, Aristotle imagined that the eyes and the ears were connected not to the brain but to blood vessels, which carried perceptions to the heart. These connections allowed the heart to govern all sensations, movements, and emotions. The brain, he wrote, simply “tempers the heat and seething of the heart.” The big brains of humans are not the source of their intelligence, Aristotle argued, but vice versa: our hearts produce the most heat, which means they need the biggest cooling system.

It was not until a few years after Aristotle’s death, in 322 B.C., that Greek anatomists emerged who were skilled enough to challenge him. In the city of Alexandria, the physicians Herophilus and Erasistratus overcame the ancient taboos and dissected hundreds of human cadavers, describing dozens of body parts for the first time, from the iris to the epididymis. Their most important achievement was the discovery of the nervous system. Earlier physicians had assumed these slender pale cords were tendons or the tips of arteries, but Herophilus and Erasistratus recognized for the first time in history that these fibers formed a distinct network that sprouted from the skull and spine.

They tried to make sense of this new nervous system in accordance with the ideas of their age. They believed that each breath carried a bit of the world-soul into the body, where it behaved just like water in a pipe. It flowed into the heart and through the arteries, bringing life to the body, some of it traveling to the brain. Herophilus and Erasistratus also discovered chambers in the middle of the brain—the ventricles—which were the only logical place for spirits to flow. Herophilus declared that these empty spaces house the intellect. From the ventricles, he believed, the spirits flow into the hollow nerves and out to the muscles, which they make bulge and move. The brain itself, he thought, had no command over the body, and even the spirits had limited power: the body’s organs could move thanks to their own natural desires.

It would take another four hundred years for someone to match the anatomical skill of Herophilus or Erasistratus. In A.D. 150, a young doctor named Galen traveled from Turkey to Alexandria to immerse himself in their teachings. He studied the human skeletons preserved at their schools and read their ancient works in the city’s libraries. Galen himself couldn’t dissect human cadavers, because Romans were even more appalled by the notion than the Greeks. And so when he returned to Turkey, he had to make do with glimpses of anatomy. As a doctor to gladiators, he could peer through the windows ripped open by tridents and spears. He dissected an animal every day. By the time he was thirty, Galen had created a new vision of the body by synthesizing Aristotle and Plato with the medicine of Hippocrates and his own observations. The result was so dazzling that when he moved to Rome, he became doctor to emperors.

Galen’s medicine rested on the transformation of food and breath into flesh and spirit. In his system, each organ had a special faculty—a soul-like power—that carried out a series of purifications. The stomach had a faculty for attracting food from the mouth down the esophagus and another faculty for cooking the food, turning it into a substance called chyle, which passed into the intestines, the surrounding veins, and the liver. The liver turned this chyle into blood. In the process, Galen argued, the liver filled the blood with a nourishing force that later physicians came to call the natural spirits. From the liver, the blood was believed to flow to the heart, passing through its left side. Impurities were attracted into the lungs, and the purified blood traveled into the veins, to be consumed by muscles and organs.

Some of the blood that entered the heart had a higher calling, supposedly trickling through the heart’s inner wall to the right side, where it mixed with air from the lungs and cooked in the heart’s innate heat, turning red and becoming imbued with vital spirits. The pulsating arteries attracted this blood and delivered its life-giving powers throughout the body.

The vital spirits that flowed up to the head underwent a final round of purification. They entered a mesh of blood vessels at the base of the skull (which came to be known as the rete mirabile, or marvelous network), where they became animal spirits, capable of thought, sensation, and movement. From there they flowed into the ventricles. Galen claimed that the ventricles were spherical, roofed with vaults of flesh, and linked by canals, designed to be inflated by the swirling animal spirits. The brain pulsated, he thought, in order to drive the spirits out into the hollow nerves, where they were driven out into the body, carrying sensations and movement.

To treat his patients, Galen restored the balance of this flow of natural, vital, and animal spirits. For instance, an overheated stomach could drive a flood of phlegm out of the brain and into the rest of the body. If there was too much blood—the hot and moist humor—a fever would strike. Purging and bloodletting could bring the humors back to their proper places, as could special herbs. But Galen believed he had discovered much more than a way to heal people: he had established a philosophy of the soul. He declared he had found the physical underpinnings of Plato’s trio of souls—the vegetative soul of the liver, responsible for pleasure and desires, the vital soul of the heart, which produced passions and courage, and the rational soul of the head.

Galen came to understand the brain far better than anyone else in the ancient world, but he was not a modern neuroscientist disguised in a toga. What we think of as the brain was to him nothing but a pump, while human intelligence was lodged in the empty spaces of the head. Moreover, that intelligence was not unique to humans but also shared by the sun, moon, and stars. In fact, their heavenly bodies were so much purer than our own that their intelligence must be far superior, able to reach down to Earth to influence human affairs. For Galen, the animal spirits swirling within us were only tiny eddies in an ocean of purpose, intelligence, and soul.

In the centuries after Galen’s death, around 199, his medicine was absorbed into the doctrines of Christianity. The early church fathers turned to him because they needed some new ideas about the brain and the soul.

According to the Old Testament, the soul is simply life itself, residing in the blood and disappearing at death. Christianity, on the other hand, anchored itself to a different sort of soul, an immortal one that faced eternal salvation or damnation. In Galen, the church fathers found a solution to this contradiction. The Old Testament soul became Galen’s lower souls of the liver and the heart. The immortal soul had no physical dimension, but the church fathers put its faculties in the empty ventricles of the head, where they could not be corrupted by weak, mortal flesh. They even went beyond Galen to assign the front ventricle to sensation, the middle to understanding, and the rear to memory. The brain itself was merely a pump, squeezing the spirits out of the ventricles and into the nerves.

Galen’s anatomy was not the only Greek idea that influenced Christianity, however. Many philosophers in Rome didn’t accept Galen’s claims about the brain, still preferring Aristotle’s theories about the heart. They liked to point out how speech came out of the chest, which meant that the heart must be its origin. To refute them, Galen gathered together physicians, philosophers, and politicians of Rome to watch him silence the roaring lions of the Coliseum by squeezing their vocal nerves. But he did not manage to silence his opponents. As a result, the Christian heart became not only the seat of the passions, but also the site of moral conscience, an organ with powers of perception beyond the senses. It is no coincidence that Jesus is often pictured with an open heart but never an open brain.

After the fall of Rome in 476, the church lost touch with its Greek origins. Not until the twelfth century did European scholars rediscover Greek philosophy through their contact with Arabs. It took a long time for Europe to become reacquainted with the likes of Aristotle and Galen. The few surviving fragments of their works had been translated into Arabic, and the Arabic translations were then translated into Latin, getting encrusted with misreadings along the way.

Many Christians were suspicious of Greek ideas that seemed to challenge the church’s teachings on the soul. Most heretical of all was the notion that the world was a void inhabited by atoms, invisibly small, indestructible particles of different shapes and sizes—twisted, round, bent, rough, and hooked. Atomists would say that the brain is not in and of itself cold; blood is not in and of itself warm. Those qualities, along with all others, emerge from the interaction of atoms that make them up. Moving through the cosmos without supervision or purpose, atoms cluster in countless different ways, producing an infinity of worlds. Epicur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction: A Bowl of Curds

- Chapter One: Hearts and Minds, Livers and Stomachs

- Chapter Two: World Without Soul

- Chapter Three: Make Motion Cease

- Chapter Four: The Broken Heart of the Republic

- Chapter Five: Pisse-Prophets Among the Puritans

- Chapter Six: The Circle of Willis

- Chapter Seven: Spirits of Blood, Spirits of Air

- Chapter Eight: A Curious Quilted Ball

- Chapter Nine: Convulsions

- Chapter Ten: The Science of Brutes

- Chapter Eleven: The Neurologist Vanishes

- Chapter Twelve: The Soul’s Microscope

- Dramatis Personae

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- References

- Index

- Copyright