eBook - ePub

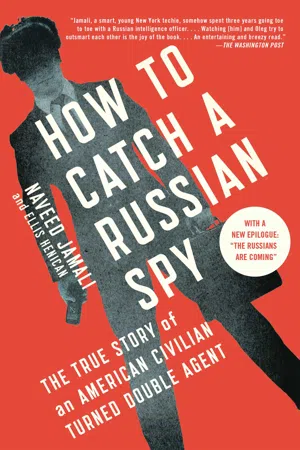

How to Catch a Russian Spy

The True Story of an American Civilian Turned Double Agent

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Catch a Russian Spy

The True Story of an American Civilian Turned Double Agent

About this book

With an epilogue on recent Russian spying, a “page-turner of a memoir” (Publishers Weekly) about an American civilian with a dream, who worked as a double agent with the FBI in the early 2000s to bring down a Russian intelligence agent in New York City.

For three nerve-wracking years, from 2005 to 2008, Naveed Jamali spied on America for the Russians, trading thumb drives of sensitive technical data for envelopes of cash, selling out his beloved country across noisy restaurant tables and in quiet parking lots. Or so the Russians believed. In fact, Jamali was a covert double agent working with the FBI. The Cold War wasn’t really over. It had just gone high-tech.

“A classic case of American counterespionage from the inside…a never-ending game of cat and mouse” (The Wall Street Journal), How to Catch a Russian Spy is the story of how one young man’s post-college-adventure became a real-life intelligence coup. Incredibly, Jamali had no previous counterespionage experience. Everything he knew about undercover work he’d picked up from TV cop shows and movies, yet he convinced the FBI and the Russians they could trust him. With charm, cunning, and bold naiveté, he matched wits with a veteran Russian military-intelligence officer, out-maneuvering him and his superiors. Along the way, Jamali and his FBI handlers exposed espionage activities at the Russian Mission to the United Nations.

Jamali now reveals the full riveting story behind his double-agent adventure—from coded signals on Craigslist to clandestine meetings at Hooter’s to veiled explanations to his worried family. He also brings the story up to date with an epilogue showing how the very same playbook the Russians used on him was used with spectacularly more success around the 2016 election. Cinematic, news-breaking, and “an entertaining and breezy read” (The Washington Post), How to Catch a Russian Spy is an armchair spy fantasy brought to life.

For three nerve-wracking years, from 2005 to 2008, Naveed Jamali spied on America for the Russians, trading thumb drives of sensitive technical data for envelopes of cash, selling out his beloved country across noisy restaurant tables and in quiet parking lots. Or so the Russians believed. In fact, Jamali was a covert double agent working with the FBI. The Cold War wasn’t really over. It had just gone high-tech.

“A classic case of American counterespionage from the inside…a never-ending game of cat and mouse” (The Wall Street Journal), How to Catch a Russian Spy is the story of how one young man’s post-college-adventure became a real-life intelligence coup. Incredibly, Jamali had no previous counterespionage experience. Everything he knew about undercover work he’d picked up from TV cop shows and movies, yet he convinced the FBI and the Russians they could trust him. With charm, cunning, and bold naiveté, he matched wits with a veteran Russian military-intelligence officer, out-maneuvering him and his superiors. Along the way, Jamali and his FBI handlers exposed espionage activities at the Russian Mission to the United Nations.

Jamali now reveals the full riveting story behind his double-agent adventure—from coded signals on Craigslist to clandestine meetings at Hooter’s to veiled explanations to his worried family. He also brings the story up to date with an epilogue showing how the very same playbook the Russians used on him was used with spectacularly more success around the 2016 election. Cinematic, news-breaking, and “an entertaining and breezy read” (The Washington Post), How to Catch a Russian Spy is an armchair spy fantasy brought to life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Catch a Russian Spy by Naveed Jamali,Ellis Henican in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

NEW AMERICANS

I always thought of myself as a fairly typical modern American kid—tech-savvy, a bit of a smart-ass, and thoroughly multicultural. Take one look at my olive complexion. That’s the future face of America, not the goofy grin of Beaver Cleaver or Richie Cunningham. I was born here, though my mom and dad were not. They arrived as immigrants from deeply chaotic places. They didn’t come to New York to toil in sweatshops or stand by pushcarts on the Lower East Side, like generations of immigrants before them. They came for graduate school, my mother from France, my father from Pakistan. They met at a party near Columbia University in 1968, just as the administration building was being occupied by student protestors, including one young man in a very cool pair of sunglasses who plopped himself in President Grayson Kirk’s leather chair and fired up an oversize cigar. There’s a famous photograph of that. I totally get where that guy was coming from. He took something that started out serious and turned it into unexpected fun.

My ancestors always had a nose for action, wherever history dropped them. The French Revolution, the partition of India, the march of science—if the world was tumbling into fresh upheaval, chances are I had relatives there. Notably, my great-great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side, Jean-Antoine Chaptal, was a world-renowned chemist credited with coining the term nitrogène (look him up on Wikipedia). Just as important as the nitrogen—maybe more so to his wine-loving countrymen—he developed a process for adding sugar to unfermented wine, which miraculously boosted the alcohol content. French oenophiles turned up their noses. There were actual demonstrations in the streets. The purists complained that the extra kick would only encourage the peasants to get drunker on the cheap stuff. But the results proved highly popular in France’s lesser wine regions. The process is still called chaptalization, after my arrière-arrière-arrière-grand-père.

À la vôtre!

Chaptal went on to found Paris Hospital. He reorganized the French loan system. Under the first emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, Chaptal was treasurer of the French Senate. He died in Paris in 1832 and was buried with his wife, Rose, in Père Lachaise Cemetery, which most Americans had never heard of until the Doors singer Jim Morrison died of an overdose and joined him there. Today Jean-Antoine’s name is inscribed on the steps of the Eiffel Tower. In light of such achievements, the rest of us were destined to seem like slackers for generations to come.

Bernard Chaptal, my mother’s father, was quite an adventurer. He worked in Argentina as a gaucho, traveled the world, returned to France, and married a Russian Jewish girl named Alice Feldzer just in time for World War II. He joined the French army and fought the Nazis valiantly. When the German blitzkrieg outflanked the Maginot Line in the spring of 1940, my grandfather escaped to Switzerland, where he spent two years in a prisoner-of-war camp. His mother-in-law and her twin sister were killed in the Holocaust.

My mother’s first name is Claude, which, in France, isn’t just a boy’s name. She was born in 1943. She, her brother, and two sisters adjusted as well as they could to the postwar shortages, though their mother was a legendarily awful cook. “She can hardly make toast, even when there is bread on the store shelves,” her children liked to tease.

My mom was a bright, creative girl. Like her father, she had a strong independent streak. She was torn between her passion for the arts and her love for science. She graduated from the Faculté de Médecine in Paris, then moved to New York to pursue a postbaccalaureate art degree at Columbia. At a grad-student party on a rare night out, she met a doctoral student of philosophy, attending New York University on a Fulbright scholarship. He had a deadpan sense of humor. He was a year older than she was. His name was Naseem Zia Jamali. He was also new to New York.

The Jamali family went as far back into the history of India as the Chaptals did in France—probably farther, though the details were not so intricately recorded. My father’s father, whose name was Zia, was a young Muslim physician in Delhi with a wife named Zora and seven little children. In 1947, when my father was five, the British divided India in two, carving out Pakistan for the Muslims and leaving the rest of the country to the majority Hindus. The young Jamali family left Delhi for Lahore and then the humid river city of Hyderabad.

The partition of India was a bloody and bitter affair, for most people, anyway. Ghost trains of massacred Muslims arrived each day in Karachi, Pakistan, as ghost trains of massacred Hindus arrived in Delhi and Bombay. When I asked my father one day how his family managed to survive the ghost trains, he answered with his usual ironic shrug. “We flew,” he said. “It was lovely.”

My father was educated the way affluent Pakistanis were—in a British-style private school where the students memorized long passages from the classics and wore neatly pressed uniforms. After graduating from college, he won the President of Pakistan merit scholarship to graduate school at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

He hated Scotland. It wasn’t just the damp, chilly weather or the bland Scottish food. The whole place felt old and unwelcoming. When he tried to rent an apartment, he was told, “Sorry, it’s already rented. I have nothing for you.”

But soon my father’s luck began to change. He won the Fulbright scholarship from the U.S. State Department and moved to New York. He entered the doctoral program at New York University, rented a tiny apartment in Greenwich Village, and began to inhale the openness and freedom and turbulence of the late 1960s. He experienced the pleasure of meeting other smart young people from around the world, including a dark-haired French woman named Claude.

Despite—or because of—the pair’s very different backgrounds, sparks flew immediately, the good kind. He was the self-deprecating philosopher-intellectual. She was the art-school graduate discovering the firmer truths of science. Both of them felt like they’d finally arrived where they belonged. They moved in together, then married, but didn’t rush to start a family. Their big-eyed, long-lashed son, Naveed Alexis Jamali, was born February 20, 1976, a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, bicentennial baby arriving at a moment of relative cultural calm and patriotism. Naveed means “bearer of good wishes” in Arabic, the “ee” being the Pakistani spelling, not the Persian “i.” My parents spoke English and French at home. I learned both as only a toddler can, weaving them together in totally haphazard ways. Other than a few simple words, I never learned to speak my father’s Urdu. My mother swears my first word was auto, which is the same in all three languages and, I am convinced, was the earliest appearance of my lifelong passion for cars.

My mom had already decided that medical school wasn’t for her. She was working as a researcher at Rockefeller University. My dad, with his fresh NYU PhD, was adjunct-teaching philosophy courses at NYU and Adelphi Universities, and traveled to NYPD stationhouses in all five boroughs to teach ethics and philosophy courses to police officers. The cops, he found, enjoyed what they thought of as the Sherlock Holmes side of police work. “Many of these guys,” he liked to say of his students in blue, “if they hadn’t become cops, you know they’d have ended up as criminals. They have a foot on either side of the law.” My father never had much of a filter between his mouth and his brain.

I was a child of the city and a child of the world. Our two-bedroom apartment on West 112th Street was just down the block from Columbia and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. My parents took me in my little stroller to the parks in the neighborhood, Central, Morningside, and Riverside. Each summer, we visited the relatives in France and Pakistan. At three, I attended the Columbia Greenhouse Nursery School on West 116th Street, one of the oldest in America, then went on to pre-K a few blocks south at the progressive Bank Street School for Children. I moved again for kindergarten, this time to the Calhoun School on West End Avenue. These were all top schools with excellent reputations. Like me, the other children came from educated families with roots around the world. My closest friend at Calhoun was a Japanese boy named Jason, whose father was a ballet instructor. Life was innocent and fun. “I like school,” I remember saying to my mom midway through kindergarten. “I’m going back tomorrow.”

But that was a tough time in New York. Crime was rising. Graffiti was everywhere. Crack cocaine hadn’t hit our neighborhood yet, but heroin definitely had. Suddenly, the tiny apartments and crowded subways felt dangerous, confining, and cramped. Coincidentally, my mother had been studying that phenomenon in her Rockefeller University lab. When I went to see her at work one day, she described her research to me. They were studying brain development using rats. This was accomplished by injecting the rats with radioactive hormones and then examining their brains to see what paths the isotopes had traveled. When I asked what happened to the rats, I learned that the experiment was good for science but not so much for the rats. Then, so the researchers could study their brains, the rats had their heads chopped off.

“You chop their heads off?” I asked my mother, excited at the drama of it but also slightly alarmed. I’d never seen a beheading on the 1 train, even in the gritty 110th Street station.

She assured me that the rules of science required it.

My parents got spooked when the super’s son was found dead in front of our apartment building. That wasn’t their idea of the Great American Dream. Abruptly, we exchanged city life for the sprawling lawns and strong public schools of New York’s northern suburbs. Our new town, Hastings-on-Hudson, wasn’t exactly a bedroom community for Wall Street. Hastings was a history-minded river town that attracted people like my parents, academic and professional types who had considered themselves city people until the first or second child came along.

That corner of Westchester County felt right to my upwardly mobile, immigrant parents. But as the crickets chirped monotonously and the stars twinkled across the broad Westchester sky, all I could think was: What kind of fun am I ever going to find up here?

I was five years old.

We had a two-family house on leafy Cochrane Avenue. Shortly before my brother, Emmanuel, arrived, we traded up to a turn-of-the-century two-story expanded colonial on the same block. My parents yanked off the white aluminum siding, installed a deck, upgraded the landscaping, tore up the driveway, built a rock garden, and turned the detached garage into a furnished studio. Actually, my mother did all that work herself, including jackhammering the driveway and removing the special garage extension installed by the previous owner to accommodate his 1962 Cadillac fins.

* * *

Moving to the suburbs was startling for me. I wasn’t the one who found the city oppressive. To me, it was an all-you-can-eat buffet of discovery, diversion, and delight. I never had trouble sleeping amid the noise of grinding garbage trucks and honking taxi horns. The nights were too quiet in Hastings-on-Hudson—what kind of name was that, anyway?—and at first I felt out of place at Hillside Elementary School on Lefurgy Avenue. Most of the other kids had started together in kindergarten. I was a year late for the in crowd, and I didn’t look like any of them. I promise you, there weren’t too many French-Pakistani children in the lunchroom or the schoolyard. There was one black girl in my whole grade. She and I were the diversity. And she had the benefit of an easy-to-pronounce name. I had to repeat mine two or three times before the other children could get it right. I toyed with the idea of calling myself “N.J.” or “Alex,” shortening my middle name. But I couldn’t get either of those to stick. I just knew that at the card-and-gift shop on Main Street, the novelty rack of mini–license plates went from Nancy straight to Norman, completely skipping Naveed.

Our first-grade teacher, Mrs. Wassenberg, was explaining to the class about Christopher Columbus and the people he met when he landed in America. She mentioned something about Indians. I raised my hand. “Like my father?” I asked.

“No,” Mrs. Wassenberg shot back. “Your father is a different kind of Indian!” I didn’t think she meant it as a compliment.

But as the school year rolled on, I gradually found my place in this strange new environment. Our school was small. We had fewer than one hundred children in each grade. One by one, we all got to know each other and found little places for ourselves.

It turned out I was funny, and funny was good. I liked to tell jokes. I knew how to make the other children laugh. I could mimic the teachers, and even some of the teachers seemed to get a kick out of that. I decided I was the official class clown. For me, making fun of myself became a survival skill. People went from laughing at me to laughing with me. I made easy friends, including some of the popular kids. By the middle of first grade, I realized how much I wanted to be part of the club. Being on the outside, I decided, really sucked.

Too bad my social prowess wasn’t being matched academically. As adept as I was at making people like me, that was how poorly I performed on my homework assignments and tests. I began to depend on my humor for more than making playground friends. I realized that as long as I was making people laugh, they weren’t getting mad at me. If they weren’t getting mad at me, I could get away with stuff.

“So, Naveed,” my teacher asked in class one day, “where’s your homework?”

“I could tell you a lie,” I answered, “but I have too much respect for you to do...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: New Americans

- Chapter 2: Family Business

- Chapter 3: Finding Me

- Chapter 4: America Attacked

- Chapter 5: Navy Dreams

- Chapter 6: Commander Lino

- Chapter 7: Special Agents

- Chapter 8: Meeting Oleg

- Chapter 9: Networkcentric

- Chapter 10: Out and About

- Chapter 11: Why Spy

- Chapter 12: Gaining Control

- Chapter 13: Agent Trust

- Chapter 14: Second Try

- Chapter 15: Worthy Adversaries

- Chapter 16: El Dorado

- Chapter 17: Easy Lies

- Chapter 18: Speeding Up

- Chapter 19: Parking Garage

- Chapter 20: Grilling Oleg

- Chapter 21: Thumb Drive

- Chapter 22: Blowing It

- Chapter 23: Hooters

- Chapter 24: Change of Plans

- Chapter 25: Phony Arrest

- Chapter 26: Victory Lap

- Chapter 27: Ensign Jamali

- Epilogue: The Russians Are Coming

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Copyright