![]()

CHAPTER 1

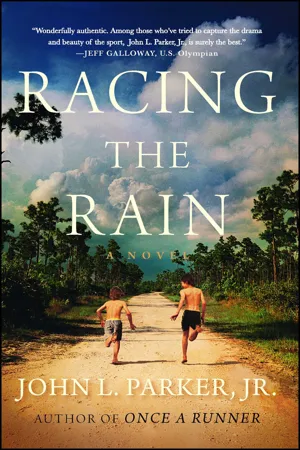

THE VERY EDGE OF THINGS

The first- and second-fastest kids in the second grade stood at the end of Rosedale Street in the early June heat, their bird chests heaving, asphalt fumes stinging their noses. They were so thin a mesh of blue veins showed under brown skin.

“It’s cuh-cuh-coming,” the smaller boy said, nodding toward the angry purple smudge on the horizon behind them. His skull was slightly elongated, somehow giving him a studious air.

“Couple minutes,” said the other, taller but just as brown and skinny, scrunching his bare toes into the sun-softened tar.

It would have been difficult for an adult to appreciate their boundless sense of possibilities as they stood waiting: the vastness of the coming summer, the endless expanse of school years ahead, the insignificance of their tiny lives when measured against any grown-up conception of time.

But for now they were simply oblivious to everything but the dark specter approaching Rosedale Street.

The sky darkened suddenly, and from nowhere a chilly wind began whipping through the Spanish moss in the live oaks across Bumby Avenue, raising goose bumps on their forearms. The boys leaned into a half crouch with hands on knees and waited.

The first fat drops splatted on the roadway, making little hissy puffs of steam, and as they began landing on the boys’ skin, a crack of thunder split the sky. They took off down the street in a blur of spindly legs and arms.

They were fairly evenly matched but were not really racing each other as much as simply trying to stay ahead of the deluge at their heels.

This moment always seemed magical to them: a bright tropical day loomed in front as a purple monsoon came on from behind. And they were thrilled as only children can be thrilled to exist for a moment at the very edge of things, at the buzzy existential margin of all possibilities. One might go fetch a Popsicle or be struck by lightning or live to a well-tended old age with golf clubs in the trunk. Whirl was king and all was in play.

All they knew was that for this moment in time they were racing the rain, and they were laughing laughing laughing.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

ANTS

The skinniest of the boys was named Quenton Cassidy. The year before, in the first grade, he had marched up to his gangly bespectacled best friend Stiggs at recess and announced: “I’m the fastest kid in first grade.”

“No, you aren’t,” Stiggs said. “He is.”

He was pointing to Demski, a spindly creature with an oblong skull and a crew cut so severe as to make his hair invisible. He was squatting in the roots of a huge live oak next to the jungle bars, enthralled by a very active colony of red ants. Demski lived on Homer Circle two blocks from Cassidy, and because his mom wouldn’t let him play pickup football, no one had paid him much attention. When they marched over, Demski didn’t look up.

“Whatcha doin’, looking at ants?” Cassidy said.

Demski nodded.

“What are they up to?” Stiggs said.

Demski shrugged. “Buh-buh-buh-building stuff, I guess.”

Cassidy and Stiggs leaned over to get a better look.

“There sure are a lot of them,” Cassidy said.

Demski nodded.

“He wants to race you,” Stiggs said. “He says he’s the fastest kid in first grade.”

“Okay,” said Demski without enthusiasm.

Several other kids had gathered around because three people watching ants apparently constituted some kind of quorum.

“Race, race!” they chanted.

“Monkey bars to home plate on the first diamond,” said Stiggs, assuming authority as usual. “I say, ‘Ready, set, go,’ and you take off. Randleman, you go stand at home in case it’s close, which it won’t be.”

Randleman, a sturdy, good-natured kid, loped off.

“Ready. Set. Go!” said Stiggs. Demski took off, but Cassidy was holding his hand up.

“Time out!” he said. “Kings X! I need to take my shoes off. I have to run barefoot.” Demski circled back, eyeing Cassidy dispassionately as he removed his Thom McAns and the ridiculous argyle socks his mother made him wear because they were a Christmas present from his great-aunt Mary and she had diabetes.

“All right, dammit,” said Stiggs, who was just learning to cuss. “Take your damn shoes off. Anything else you need? Want to change your clothes or have a little snack?” The small crowd laughed. Stiggs, everyone agreed, was the wittiest kid in first grade.

When Cassidy was finally ready and he and Demski were crouched side by side, Stiggs held his arm in the air dramatically.

“Ready. Set. Go!” Apropos of nothing, he added another “Dammit.”

Ed Demski really was the fastest kid in first grade, so it wasn’t much of a contest, though Cassidy surprised everyone by making it close.

Stiggs was standing by the monkey bars, arms folded smugly across his chest, as Cassidy came back to get his shoes and socks, still panting.

“What do you say now, big mouth?” Stiggs said as the bell rang.

Cassidy sat on the ground with spindly legs crossed, vigorously shaking sand out of a shoe. He looked up at Stiggs and brightened.

“Hey, Stiggs,” he said, “guess what? I’m the second-fastest kid in first grade!”

![]()

CHAPTER 3

PARCHED

They were always thirsty.

It would be ninety-two in the shade by midmorning and they would stop their front yard ball game and disperse to houses known to serve Kool-Aid, returning with faint clown smiles of various flavors. Or they would gobble plasticky water from the hose after running it for a while to get all the hot out. At the school gym they’d take a break from the shirts-and-skins basketball game to crowd around the rumbling old watercooler, urging the guy in front to goddamn hurry up! Hey, spaz, leave some for the fish! Hey, ya big jerk, you’re not a camel!

Sometimes they’d see the edges of a little grin protruding from either side of the pencil-thin stream of frigid water, and they’d go thirst crazy.

“Dammit, Stiggs!” And a writhing body would be pulled away from the fountain and briefly pummeled.

If anyone had money, they would race their bicycles through the wavy afternoon heat to the A&W, where the root beer mugs were frozen so solidly they gave off smoke in the afternoon heat and at some point a perfectly round medallion of ice would detach from the bottom and float majestically up through the bubbles to bob around in the foamy surface before being crunched by little teeth. Sometimes they’d pedal to Palm Drugs for a five-cent Pepsi, which the soda jerk would have to mix manually and which they would nurse for a half hour or more, not leaving the blessed air-conditioning until they had pried the last melting morsel of ice from the bottom of the glass with a straw.

Food mattered little to them and they tried not to waste too much time at their Formica kitchen tables, but their thirst was another matter. It would make them so desperate they would sometimes gulp water right from the lake or the river they were swimming in, despite admonitions from adults.

He and Stiggs and Randleman were on Rosedale Street; Joe and Johnny Augenblick, proprietors of a decent backyard basketball court, were one street over on Betty Drive, as were Buddy Lockridge and Billy Claytor. Demski was two blocks away on Homer Circle. The girls were playmates of last resort, but some of them were okay: Libby Claytor, Patty Robertson, Bonnie Johnson, and of course the adorable Maria DaRosa. They even knew some kids from six and seven blocks away, all the way up to Chelsea Street and Christy Avenue, though they seemed a bit foreign and exotic.

Cassidy was vaguely proud that his own roots went deeper than most of the others’, whose families came after the war, pouring back down to the sunny reptile farms and honky-tonk beaches dad had discovered in boot camp or flight school. Many were among the new breed of electronic warrior more at home with soldering irons, capacitors, and resistors than with guns and tanks. They worked on Air Force radar at Fort Murphy or Navy sonar at Lake Gem Mary or on one of dozens of cold war projects up and down the state, some as civilians, some still “in.” Others came down to start businesses or to take jobs in the newly awakened economy. No one had heard the term “baby boom,” but they were all nonetheless in the business of producing offspring, herds of skinny young’uns who grew up in baking pastel cinder-block houses in those wondrous days when air-conditioning was just a cruel rumor.

Cassidy would never forget endless summer nights perspiring on damp sheets, the faint hope of sleep just a fever dream. The droning arc of the rotating fan would bring a few seconds of blessed relief before sweeping past and lingering uselessly for a moment at the far end of its cycle.

Most of the children around Rosedale Street had never hurled a snowball, but they had flung many a rotten orange. That was one reason they loved winter, when the heat would finally back off, and abundant ammunition lay all around on the ground, courtesy of the remnants of the old citrus groves their houses were built among.

Most of the year they lived like simians, sometimes sitting right in the trees while munching on the flora. Or they would pull fruit from limbs as they ran by: loquats, a kind of sweet yellow plum with a single big seed; Brazilian cherries, which were miniature red-orange pumpkins that grew on hedges and were sweet but had a slightly nasty aftertaste; pink-fleshed guavas and red-yellow mangoes; fat little fig bananas; and of course citrus of all kinds, most of which dropped unnoticed from ignored trees. After a few days the oranges were mushy and fermented, perfect for rendering friends and enemies sticky, smelly, and spoiling for revenge. Mothers did a lot of laundry.

They got sandspurs in their feet, sunburns on their backs, and boils all over from the sandy soil. They were bitten by mosquitoes, chiggers, and occasionally each other. They were as at home in water as they were on land, and by the age of twelve many of them had landed their first sailfish or marlin. Most could throw a cast net, paddle a canoe, and handle a gaff.

In the happy midpoint of the twentieth century, Quenton Cassidy and the other kids on Rosedale Street grew up this way in Citrus City, a pebble toss away from the Atlantic Ocean, in the southern part of a coral peninsula the Spaniards named for flowers.

![]()

CHAPTER 4

NUCLEAR OBLIVION

By third grade, softball had become Cassidy’s second-favorite sport, so there was nothing unusual about being still sweaty from a before-school game of scrub. This morning it made his iron-hard desk seat even more uncomfortable than usual, not helped by the fact that he’d picked up some well-placed grains of sand in his underwear sliding into home for no particular reason.

A determined bumblebee was trying to bump his way through one of the window screens, and Cassidy watched it with interest as he desperately maneuvered his itchy butt cheeks around.

Mrs. Chickering, whose elaborately rhinestoned eyeglasses lent wings to her pretty dark eyes, was going on and on about the exports of Paraguay. She stopped in midsentence, marking her place with a forefinger and lowering her book. She focused her lovely eyes on Cassidy with ill-concealed exasperation.

“Quenton, do you need the hall pass?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Then will you please stop squirming?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

The class tittered, as it always did when someone got in trouble. Mrs. Chickering went back to discussing “hardwoods,” a mystery to Cassidy. It seemed to him that wood in general was hard (his satanic desk seat being a case in point), and if it wasn’t, then what good was it anyway? What use could possibly be made of soft wood?

Such are the diversions of a lively child stunned by humidity and boredom. Trying to take his mind from his inflamed backside, he surreptitiously kept track of the relentless bee.

At long last Mrs. Chickering put her book away and picked up a mimeographed sheet from her desk.

“All right, children, we have art after lunch, so Miss Baskind will be here. I expect that you will be well-behaved ladies and gentlemen and that no one will have to come fetch me from the teachers’ lounge,” she said. An excited murmur swept through the room. Everyone liked art.

“All right, settle down. In a few minutes we will be heading to assembly. As always, there will be no talking once we are in line, and no talking while we are marching to the auditorium. Does everyone understand that? Carl Wagner? Olivia Lattermore? Quenton Cassidy?”

The class chatterboxes dutifully muttered assent, but Mrs. Chickering paused for an interminable few seconds to emphasize her point. Not before everyone was suitably uncomfortable did she continue reading from the sheet.

“This morning in the auditorium we will see a movie from the United States Office of Civil Defense featuring Bert, the civil defense turtle. After assembly we will spend fifteen minutes practicing the duck-and-cover drills that we learn about in the movie.”

More murmuring now. This was shaping up to be a pretty good day. Any event that broke the monotony of memorizing the exports of South American countries was entirely welcome. No one really knew what civil defense was, but Bert was apparently a cartoon turtle of some kind, and anything having to do with cartoons, even a government turtle, was good.

It was the most natural thing in the world to Quenton Cassidy, his classmates, and everyone he knew, to be living in a booming, vaguely militarized postwar America that went to bed dreaming not only of Amana freezers and Mohawk carpeting, but also of mushroom clouds and foreign paratroopers.

The current boogeyman was the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly referred to as “the Russians,” a theoretically Marxist operation that in actuality was an entire society organized around the guiding principles of the United States Post Office.

The Soviets couldn’t for the life of them produce a decent pair of Levi’s or a grade of toilet paper that didn’t actually dr...