- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

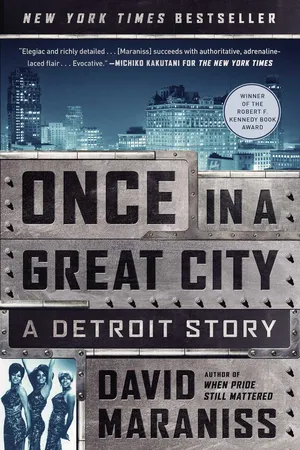

“A fascinating political, racial, economic, and cultural tapestry” (Detroit Free Press), Once in a Great City is a tour de force from David Maraniss about the quintessential American city at the top of its game: Detroit in 1963.

Detroit in 1963 is on top of the world. The city’s leaders are among the most visionary in America: grandson of the first Ford; Henry Ford II; Motown’s founder Berry Gordy; the Reverend C.L. Franklin and his daughter, the incredible Aretha; Governor George Romney, Mormon and Civil Rights advocate; car salesman Lee Iacocca; Police Commissioner George Edwards; Martin Luther King. The time was full of promise. The Detroit auto industry was selling more cars than ever before. Yet the shadows of collapse were evident even then as urban decline and racial tension simmered beneath the surface.

“Elegiac and richly detailed” (The New York Times), in Once in a Great City David Maraniss shows that before the devastating riot, before the decades of civic corruption and neglect, and white flight; before people trotted out the grab bag of rust belt infirmities and competition from abroad to explain Detroit’s collapse, one could see the signs of a city’s ruin. Detroit at its peak was threatened by its own design. It was being abandoned by the new world economy and by the transfer of American prosperity to the information and service industries. In 1963, as Maraniss captures it with power and affection, Detroit summed up the American Dream of prosperity that was already past history. “An encyclopedic account of Detroit in the early sixties, a kind of hymn to what really was a great city” (The New Yorker).

Detroit in 1963 is on top of the world. The city’s leaders are among the most visionary in America: grandson of the first Ford; Henry Ford II; Motown’s founder Berry Gordy; the Reverend C.L. Franklin and his daughter, the incredible Aretha; Governor George Romney, Mormon and Civil Rights advocate; car salesman Lee Iacocca; Police Commissioner George Edwards; Martin Luther King. The time was full of promise. The Detroit auto industry was selling more cars than ever before. Yet the shadows of collapse were evident even then as urban decline and racial tension simmered beneath the surface.

“Elegiac and richly detailed” (The New York Times), in Once in a Great City David Maraniss shows that before the devastating riot, before the decades of civic corruption and neglect, and white flight; before people trotted out the grab bag of rust belt infirmities and competition from abroad to explain Detroit’s collapse, one could see the signs of a city’s ruin. Detroit at its peak was threatened by its own design. It was being abandoned by the new world economy and by the transfer of American prosperity to the information and service industries. In 1963, as Maraniss captures it with power and affection, Detroit summed up the American Dream of prosperity that was already past history. “An encyclopedic account of Detroit in the early sixties, a kind of hymn to what really was a great city” (The New Yorker).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Once in a Great City by David Maraniss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

GONE

THE NINTH OF NOVEMBER 1962 was unseasonably pleasant in the Detroit area. It was an accommodating day for holiday activity at the Ford Rotunda, where a company of workmen were installing exhibits for the Christmas Fantasy scheduled to open just after Thanksgiving. Not far from a main lobby display of glistening next-model Ford Thunderbirds and Galaxies and Fairlanes and one-of-a-kind custom dream cars, craftsmen were constructing a life-size Nativity scene and a Santa’s North Pole workshop surrounded by looping tracks of miniature trains and bountiful bundles of toys. This quintessentially American harmonic convergence of religiosity and consumerism was expected to attract more than three-quarters of a million visitors before the season was out, and for a generation of children it would provide a lifetime memory—walking past the live reindeer Donner and Blitzen, up the long incline toward a merry band of hardworking elves, and finally reaching Santa Claus and his commodious lap.

The Ford Rotunda was circular in an automotive manufacturing kind of way. It was shaped like an enormous set of grooved transmission gears, one fitting neatly inside the next, rising first 80 then 90 then 100 then 110 feet, to the equivalent of ten stories. Virtually windowless, with its steel frame and exterior sheath of Indiana limestone, this unusual structure was the creation of Albert Kahn, the prolific architect of Detroit’s industrial age. Kahn had designed it for the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago, where Ford’s 1934 exhibit hall chronicled the history of transportation from the horse-drawn carriage to the latest Ford V-8. When that Depression-era fair shuttered, workers dismantled the Rotunda and moved it from the south side shore of Lake Michigan to Dearborn, on the southwest rim of Detroit, where it was reconstructed to serve as a showroom and visitors center across from what was then Ford Motor Company’s world headquarters. Later two wings were added, one to hold Ford’s archives and the other for a theater.

In the fullness of the postwar fifties, with the rise of suburbs and two-car garages and urban freeways and the long-distance federal interstate system, millions of Americans paid homage to Detroit’s grand motor palace. For a time, the top five tourist attractions in the United States were Niagara Falls, the Great Smokey Mountains National Park, the Smithsonian Institution, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Ford Rotunda. The Rotunda drew more visitors than Yellowstone, Mount Vernon, the Statue of Liberty, or the Washington Monument. Or so the Ford publicists claimed. Chances are you have not heard of it.

To appreciate what the Rotunda and its environs signified then to Detroiters, a guide would be useful, and for this occasion Robert C. Ankony fills the role. Ankony (who went on to become an army paratrooper and narcotics squad officer, eventually earning a PhD in sociology from Wayne State University) was fourteen in November 1962, a chronic juvenile delinquent who specialized in torching garages. Desperate to avoid drudgery and boredom, he knew the Rotunda the way a disaffected boy might know it. Along with the Penobscot Building, the tallest skyscraper downtown, the Rotunda was among his favorite places to hang out when he played hooky, something he did as often as possible, including on that late fall Friday morning.

“The Highway” is what Ankony and his friends called the area where they lived in the southwest corner of Detroit. The highway was West Vernor, a thoroughfare that ran east through the neighborhood toward Michigan Central Station, the grand old beaux arts train depot, and west into adjacent Dearborn toward Ford’s massive River Rouge Complex, another Albert Kahn creation and the epicenter of Ford’s manufacturing might. In Detroit Industry, the legendary twenty-seven-panel murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts painted by Diego Rivera and commissioned by Edsel Ford, the founder’s son, among the few distinguishable portraits within the scenes of muscular Ford machines and workers is that of Kahn, wearing wire-rim glasses and work overalls. Ankony experienced Detroit industry with all of his senses: the smoke and dust and smells drifted downwind in the direction of his family’s house two miles away on Woodmere at the edge of Patton Park. His mother, Ruth, who could see the smokestacks from her rear window, hosed the factory soot off her front porch every day. What others considered a noxious odor the Ankonys and their neighbors would describe as the smell of home.

On the morning of November 9, young Bob reported to Wilson Junior High, found another boy who was his frequent collaborator in truancy, and hatched plans for the day. After homeroom, they pushed through the double doors with the horizontal brass panic bars, ran across the school grounds and over a two-foot metal fence, scooted down the back alley, and were free, making their way to West Vernor and out toward Ford country.

It was a survival course on the streets, enlivened by the thrill of avoiding the cops. Slater’s bakery for day-old doughnuts, claw-shaped with date fillings, three cents apiece. Scrounging curbs and garbage cans for empty soda bottles and turning them in for two cents each. If they had enough pennies, maybe go for a dog at the Coney Island on Vernor. Rounding the curve where Vernor turned to Dix, past the Dearborn Mosque and the Arab storefronts of east Dearborn. (Ankony’s parents were Lebanese and French; he grew up being called a camel jockey and “little A-rab.”) Fooling around at the massive slag piles near Eagle Pass. Dipping down into the tunnel leading toward the Rouge, leaning over a walkway railing and urinating on cars passing below, then up past the factory bars, Salamie’s and Johnny’s, and filching lunches in white cardboard boxes from the ledge of a sandwich shop catering to autoworkers on shift change. Skirting the historic overpass at Miller Road near Rouge’s Gate 4, where on an afternoon in late May 1937 Walter Reuther and his fellow union organizers were beaten by Ford security goons, a violent encounter that Ankony’s father, who grew up only blocks away, told his family he had witnessed. Gazing in awe at the Rouge plant’s fearsomely majestic industrial landscape from the bridge at Rotunda Road, then on to the Rotunda itself, where workmen were everywhere, not only inside installing the Christmas displays but also outside repairing the roof.

To Ankony, the Rotunda was a wonderland. No worries about truant officers; every day brought school groups, so few would take notice of two stray boys. With other visitors, including on that day a school group from South Bend, they took in the new car displays and a movie about Henry Ford, then blended in with the crowd for a factory tour that left by bus from the side of the Rotunda over to the Rouge plant, then the largest industrial complex in the United States. Ankony had toured the Rouge often, yet the flow of molten metal, the intricacies of the engine plant, the mechanized perfection of the assembly, all the different-colored car parts coming down the line and matching up, the wonder of raw material going in and a finished product coming out, the reality of scenes depicted in Rivera’s murals, thrilled him anew every time. The Rouge itself energized him even as Rivera’s famed murals frightened him. The art, more than the place itself, reminded him of the gray, mechanized life of a factory worker “in those dark dungeons” that seemed expected of a working-class Detroit boy and that he so much yearned to avoid.

When the Rouge tour ended in early afternoon, Ankony and his pal had had enough of Ford for the day and left for a shoplifting spree at the nearby Montgomery Ward store at the corner of Schaefer Road and Michigan Avenue, across the street from Dearborn’s city hall. They were in the basement sporting goods department, checking out ammo and firearms, when they heard a siren outside, then another, a cacophony of wailing fire trucks and screeching police cars. The boys scrambled up and out and saw smoke billowing in the distance. Fire!—and they didn’t start it. Fire in the direction of the Rotunda. They raced toward it.

Roof repairmen since midmorning had been taking advantage of the fifty-degree weather to waterproof the Rotunda’s geodesic dome panels. Using propane heaters, they had been warming a transparent sealant so that it would spray more easily. At around 1 p.m., a heater ignited sealant vapors, sparking a small fire, and though workmen tried to douse the flames with extinguishers they could not keep pace and the fire spread. The South Bend school group had just left the building. Another tour for thirty-five visitors was soon to begin. There was a skeleton staff of eighteen office workers inside; many Rotunda employees were at lunch. A parking lot guard noticed the flames and radioed inside. Alarm bells were sounded, the building was evacuated, the roof repairmen crab-walked to a hatch and scrambled down an inside stairwell, and the Dearborn and Ford fire departments were summoned, their sirens piercing the autumn air, alerting, among others, two truant boys in the Monkey Ward’s basement.

By the time firefighters reached the Rotunda, the entire roof, made of highly combustible plastic and fiberglass, was ablaze. Two aerial trucks circled around to the rear driveway. From the other side, firefighters and volunteers stretched hoses from Schaefer Road and moved forward cautiously. It was too hot, and the water pressure too limited, to douse the fire with sprays up and over the 110 feet to the roof. The structure’s steel frame began to buckle. At 1:56, fire captains ordered their men away from the building, just in time. Robert Dawson, who worked in the Lincoln-Mercury building across the street, looked over and saw a “ball of fire” on the roof but at first no flames below. “Suddenly the roof crashed through. Everything inside turned to flame. Smoke began sifting through the limestone walls. Then, starting at the north corner, the walls crumbled. It was as though you had stacked dominoes and pushed them over.” The fire had reached the Christmas displays, fresh and potent kindling, and raged out of control, bright flames now shooting fifty feet into the sky. The entire building collapsed in a shuddering roar, a whirlwind of hurtling limestone and concrete and dust.

Fire officials, aided by a prevailing northeast wind, concentrated on saving the north wing, where the Ford archives were stored. The south wing was already gone, its 388-seat theater a crisped shell. At the perimeter, Bob Ankony and his buddy angled for a closer look. “There were a bunch of security guys there trying to keep us back. One guy, we were pushing him to get past. We wanted to get right up to the fire,” Ankony recalled. “I was into burning garages. We had torched garages with cars in them. Now we just wanted to see cars on fire. We were youths and stupid.” The security guard held them back. The boys picked up chunks of rock and dirt and started throwing them at the guard. This attracted the attention of some nearby Dearborn cops, who took the teenagers into custody and hauled them to the police station.

For days thereafter, Ankony and his pal held exalted status among the Cabot Street Boys, the gang of young delinquents in his southwest Detroit neighborhood. Word spread that they had taken their petty arson up several notches and burned down the great Rotunda. The more they denied it, the more they were disbelieved.

The rest of Detroit was mourning the loss. In his “Town Crier” column, Mark Beltaire of the Free Press, who as a teenager had visited the original Rotunda pavilion at the fair in Chicago, wrote, “Tears for a building? Of course, and many when such as the Ford Rotunda dies. Over the years the Rotunda acquired a special personality all its own. It was known and recognized by people who had never been inside. They were aware of the Rotunda especially by night, even while driving many miles away.” Another columnist wrote that the Rotunda “had stood for more than a quarter century as testimony to Detroit’s industrial eminence. Its history was wrapped inextricably with that of the modern automotive industry.” The Rotunda’s manager, John G. Mullaly, who had been on leave to organize Ford Motor Company pavilions at the Seattle and New York World’s Fairs, returned to tour the charred remains with the manager of the Christmas program. Fifteen million dollars up in smoke, a holiday tradition ruined, and a symbol of the Motor City’s might in ashes, the visitor count permanently capped at 13,189,694. Mullaly and his boss, Henry Ford II, would not say so publicly yet, but it was obvious that the Ford Rotunda could not and would not be rebuilt. Something was forever gone.

• • •

Late that same afternoon, as firefighters hosed down the remains of the Rotunda, George Edwards, commissioner of the Detroit Police Department, sat twelve miles away at 1300 Beaubien, waiting anxiously for his desk phone to ring. The address was literal and figurative: 1300 Beaubien was police headquarters and also shorthand for cop brass. The ten-story building was yet another Albert Kahn creation, hulking on a city block between Clinton and Macomb. Edwards had been at his job less than a year. He had stepped down from the Michigan Supreme Court and taken the top cop job at the behest of Detroit’s new mayor, Jerome Cavanagh, a liberal Catholic acolyte of President Kennedy, and was tasked with reforming the force, making it more citizen-friendly, improving its relationship with the city’s black population, or “Negro community,” as it was called then. “It may well be that in the next several years the greatest contribution that I can make lies in seeking to resolve the dangerous tensions which threaten Detroit, and in seeking to make the Constitution a living document in one of our great cities,” Edwards wrote to a close friend in a letter explaining the “improbable sequence of events” that led him to take the position. But even with that idealistic vision, his primary job as commissioner, always, was to fight crime, and the word he now so anxiously awaited dealt with the complicated nexus of those two missions.

The phone call finally came three and a half hours later, at 8:30 that night. Senior Inspector Art Sage, head of the vice squad, was on the other end of the line. “Boss, we got it,” Sage reported triumphantly. “We got the whole schmozzle.”

The whole schmozzle in this case was the gambling operation run out of the Gotham Hotel, long known to local cops and feds as the iron fortress of the numbers racket in Detroit. In the late afternoon dimness, two Department of Street Railways buses had pulled up to the establishment off John R Street at 111 Orchestra Place. The doors whooshed open, and out stormed 112 men wielding fire axes, crowbars, and sledgehammers from a joint task force of Detroit police, Michigan state police, and the intelligence unit of the Internal Revenue Service. The first officers off the bus also carried a warrant to search the entire hotel. Never before had they been able to obtain such a sweeping search warrant; for previous raids, of a more modest scale, they had had to ask for legal authority to search one room, two or three at most, and had been foiled by the gamblers, who protected their fortress with a sophisticated system of internal security monitors, alarms, and spies working inside the hotel and circling the nearby streets with two-way radios.

This time a federal undercover agent was planted inside for the single purpose of beating the desk clerk to the alarm buzzer, which he succeeded in doing. With a plan, an expansive warrant, and a full raiding company eager to go, the odds seemed better that the law would find what it was after. “They broke in here like members of the Notre Dame football team,” John J. White, the Gotham’s proprietor, told a sympathetic reporter from the Michigan Chronicle. In its headline of the raid, Detroit’s leading black newspaper inserted the word “raging” before “football team.”

The Gotham was not just any hotel. In its day, it was the cultural and social epicenter of black Detroit. John White was a capitalist success story, a small-town kid from Gallipolis, Ohio, who came to the big city with his siblings after his mother died, hovered around the gamblers and off-books financiers of Hastings Street, and eventually acquired enough money to buy the hotel in 1943. At a time when that section of town—not far from Wayne State University, one block from Woodward Avenue, and a short walk from Orchestra Hall—was mostly white, he extended the perimeter of the historically black district known as Paradise Valley. The Gotham, two solid brick towers connected in the middle with a penthouse on top, had once been the grand personal residence of Albert D. Hartz, who made his millions selling medical supplies. It was built for him by—who else?—architect Albert Kahn.

To walk into the Gotham on any day for most of the two decades after White took over was to enter a hall of fame of black culture. Everyone had stayed there. On the wall behind the front desk were signed photographs of Jackie Robinson, Joe Louis, Adam Clayton Powell, and the Ink Spots. The Brown Bomber, who had grown up in Detroit from age twelve, became a breakfast regular in the Gotham’s Ebony Room, ordering five scrambled eggs with ketchup and a bone-in steak. The hotel’s front counter had been built by Berry Gordy Sr., a jack-of-all-trades and father of the namesake president of Motown Records. Berry Gordy Jr.’s four older sisters—and soon enough all of Motown’s women singers—were taught etiquette, posture, and social graces by Maxine Powell, who stayed at the Gotham for many years and held classes there. On a wall behind the thickly cushioned leather chairs in the lobby were color portraits of Sugar Ray Robinson, Judge Wade McCree, Congressman Charles Diggs Jr., and other black notables. John Conyers Jr., a young lawyer who would go on to join Diggs in Congress, made his way through Wayne State University Law School by selling Filter Queen vacuum cleaners; his biggest sale was to John White and the Gotham housekeeping staff. The Gotham deal was of such note, Conyers recalled, that it was reported in the following Wednesday’s edition of the Michigan Chronicle. The leading black businessmen in Detroit gathered regularly at the hotel in formal-wear for events of the Gotham Club, distinguished fellows who were also lifetime members of the Detroit branch of the NAACP.

Employees at the Gotham were instructed to follow John White’s courtesy code, which was printed and posted on every floor: Never argue with a guest. It is never enough to be pleasant only with our guests. Spread it around among your fellow workers also. Gu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Map of the Midwest

- Author’s Note

- 1. Gone

- 2. Ask Not

- 3. The Show

- 4. West Grand Boulevard

- 5. Party Bus

- 6. Glow

- 7. Motor City Mad Men

- 8. The Pitch of His Hum

- 9. An Important Man

- 10. Home Juice

- 11. Eight Lanes Down Woodward

- 12. Detroit Dreamed First

- 13. Heat Wave

- 14. The Vast Magnitude

- 15. Houses Divided

- 16. The Spirit of Detroit

- 17. Smoke Rings

- 18. Fallen

- 19. Big Old Waterboats

- 20. Unfinished Business

- 21. The Magic Skyway

- 22. Upward to the Great Society

- Epilogue: Now and Then

- Connections

- Time Line

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Copyright