- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

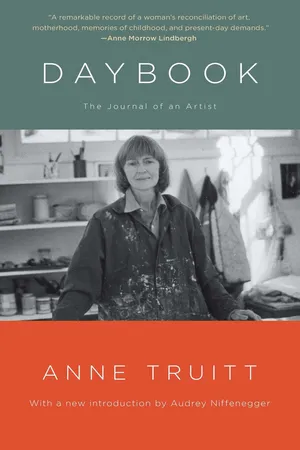

A “touchstone for aspiring artists and writers” (Megan O’Grady, The New Yorker), Daybook is a classic work about reconciling the call of creative work with the demands of daily life.

Renowned American artist Anne Truitt kept this illuminating and inspiring journal over a period of seven years, determined to come to terms with the forces that shaped her art and life. Her range of sensitivity—moral, intellectual, sensual, emotional, and spiritual— is remarkably broad. She recalls her childhood on the eastern shore of Maryland, her career change from psychology to art, and her path to a sculptural practice that would “set color free in three dimensions.” She reflects on the generous advice of other artists, watches her own daughters’ journey into motherhood, meditates on criticism and solitude, and struggles to find the way to express her vision. Resonant and true, encouraging and revelatory, Anne Truitt guides herself—and her readers—through a life in which domestic activities and the needs of children and friends are constantly juxtaposed against the world of color and abstract geometry to which she is drawn in her art.

Beautifully written and a rare window on the workings of a creative mind, Daybook showcases an extraordinary artist whose insights generously and succinctly illuminate the artistic process.

Renowned American artist Anne Truitt kept this illuminating and inspiring journal over a period of seven years, determined to come to terms with the forces that shaped her art and life. Her range of sensitivity—moral, intellectual, sensual, emotional, and spiritual— is remarkably broad. She recalls her childhood on the eastern shore of Maryland, her career change from psychology to art, and her path to a sculptural practice that would “set color free in three dimensions.” She reflects on the generous advice of other artists, watches her own daughters’ journey into motherhood, meditates on criticism and solitude, and struggles to find the way to express her vision. Resonant and true, encouraging and revelatory, Anne Truitt guides herself—and her readers—through a life in which domestic activities and the needs of children and friends are constantly juxtaposed against the world of color and abstract geometry to which she is drawn in her art.

Beautifully written and a rare window on the workings of a creative mind, Daybook showcases an extraordinary artist whose insights generously and succinctly illuminate the artistic process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Daybook by Anne Truitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Artist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Artist Biographies1 JANUARY

The ground smells of spring. I am glad to be delivered once more from the dark solstice into the turn toward growth. January is my favorite month, when the light is plainest, least colored. And I like the feeling of beginnings.

3 JANUARY

In 1933, when I was twelve, the axe fell on the sunny progression of my days. The Depression, which temporarily annihilated my father’s income and cut my mother’s, laid waste to my childhood suddenly and unexpectedly. It seemed to me that one day all was as it had always been and the next both my parents were sick; our old nurse, retired; our cook, who had also been with us for years, replaced; and I was left virtually in charge of the household. My mother was in a hospital in Baltimore for almost the entire winter of 1933–34. My father, stricken beyond his capacity to rise above his circumstances, took to getting “sick.” He had “flu” regularly, and gradually I understood that this meant he got drunk regularly. I was profoundly ashamed of him. Considering it now, I wonder why some grown-up person didn’t take charge more. My parents had friends. But no one did anything, and I was left to gather my forces and give what orders were given to run the house and to see that the schedule was maintained, cheerlessly but competently. I did my homework in my usual place, at a small, delicate French desk in the library, but nothing else was as it had been.

Now that alcoholism is recognized as a commonplace and shameless disorder, it is difficult to realize that even so short a time ago as my own childhood there was no help offered in such situations. The doctor who came to see my father when matters became critical, and who ordered him a nurse for a while, was kind enough; but I picked up his embarrassment. In response, I closed my doors and retired, as I had observed my mother doing, into routine and pride.

And so the whole world in which I had bloomed so happily, enjoying my crises as well as my pleasures, was overtaken by a twilight. But that, too, ended when, in the spring of 1934, my sisters and I went to spend the summer with my mother’s sister, my dear aunt Nancy, on her farm in Virginia. The summer stretched into the winter, my parents continued to be sick, the house in Easton was sold, and in the fall of 1935 our whole family moved south to Asheville, North Carolina. But by that time I had changed. Nurtured among seven children, we three and my four cousins, I had recovered my childishness and then begun to outgrow it more naturally.

3 JANUARY

The exhibit of the Arundel paintings at the Baltimore Museum of Art is now beginning to magnetize events. The paintings pull together in my head. An exhibit exists long before it is installed, and is delivered by a series of familiar decisions and actions.

4 JANUARY

The Renaissance emphasis on the individuality of the artist has been so compounded by the contemporary fascination with personalities that artists stand in danger of plucking the feathers of their own breast, licking up the drops of blood as they do so, and preening themselves on their courage. It is not surprising that some come to suicide, the final screw on this spiral of self-exploitation. And particularly sad because the artist’s impulse is inherently generous. But what artists have to give and want to give is rarely matched and met. The public, themselves deprived of the feeling of community that grants due proportion to everyone’s self-expression, yearn over the artist in some special way because he or she seems to have the magic to wrench color and meaning from their bleached lives. The artist gives them themselves. They can even buy themselves.

6 JANUARY

While we were visiting in England during the summer of my eleventh year, my mother took me alone one afternoon to Westminster Abbey. We entered through the great portal and walked down the nave, stopping off here and there to see the tombs of people who had been—until the moment I saw the places where they were buried—abstractions, storybook people. We then made our way out into the cloisters, and there my mother explained to me the construction of the cathedral. As she spoke, I saw with utter clarity how the outside of the building matched the inside, and felt with a lifting of my heart the immense interior space upheld by the buttresses and flying buttresses that proliferated one against the other to raise the walls and to anchor them to the supporting earth. In a few brief words, she gave me the concept of intelligent and ingenious construction, of solution; I saw clearly that people had had an idea and then had thought up a way to make that idea real. And also that the idea had to do with their feelings about the nature of God, their highest feelings, those about which they felt most passionate. I saw too that it must have been an exceedingly difficult feat, and that many people had had to work together on a common plan. The lives of those who conceived the abbey, and those who had worked on it, and those who were buried in it came together in my mind. Theirs was a fellowship both anonymous and famous, dedicated to the realization of their highest ideals.

All this reverberated within me, but what most struck me was the actual construction itself, the solution of the apparently insoluble problem of raising walls so high into the air. From then on, I looked at buildings with a different, more speculative eye. How did they fit? How did the outside match the inside? And, by the extrapolation of this curiosity as I grew older, I became sensitive to how every appearance has something inside that explains how it looks.

Reverence, nurtured by our evening prayers, which my mother always heard at our bedsides, and by the Sunday school to which we went regularly in Christ Church next door to our house, had long been one of the deepest roots of my feeling. It had not yet occurred to me that this feeling could be expressed. Westminster Abbey taught me that, given intelligence, industry, and passion, such awe could be made actually to exist, transmuted into symbol.

7 JANUARY

Of all the Ten Commandments, “Thou shalt not murder” always seemed to me the one I would have to worry least about, until I got old enough to see that there are many different kinds of death, not all of them physical. There are murders as subtle as a turned eye. Dante was inspired to install Satan in ice, cold indifference being so common a form of evil.

10 JANUARY

There is an appalling amount of mechanical work in the artist’s life: lists of works with dimensions, prices, owners, provenances; lists of exhibitions with dates and places; bibliographical material; lists of supplies bought, storage facilities used. Records pile on records. This tedious, detailed work, which steadily increases if the artist exhibits to any extent, had been something of a surprise to me. It is all very well to be entranced by working in the studio, but that has to be backed up by the common sense and industry required to run a small business. In trying to gauge the capacity of young artists to achieve their ambition, I always look to see whether they seem to have this ability to organize their lives into an order that will not only set their hands free in the studio but also meet the demands their work will make upon them when it leaves the studio. The “enemies of promise,” in Cyril Connolly’s phrase, are subtle, guileful, and resourceful. Talent is mysterious, but the qualities that guard, foster, and direct it are not unlike those of a good quartermaster.

11 JANUARY

An exhibit that is coming along well is cheerful. Yesterday John Gossage and Renato Danese, the co-curators of the Baltimore Museum of Art exhibit, and I strode around the museum as if on our native heath, making decisions together, with the zest of experience. This lightheartedness in no way denies our knowledge that much could go wrong before our concept of the exhibit becomes real.

The point at which decision is brought to bear on process is that at which two opposing forces meet and rebound, leaving an interval in which a third force can act. The trick of acting is to catch this moment. When it all happens well, a happy feeling of swinging from event to event results, a sort of gymnastic pleasure. Yesterday Renato thought an exhibition room should be unified by pigeon gray; John thought the photographs would line up into nonentity in such a flat environment. They turned to me. I suggested a third solution incorporating both insights; we all rose to it and took the wave of decision as one.

It was Gurdjieff who dissected this process for me to examine, and I like to watch it happening. His analysis of process into octaves is also fascinating to me, and very helpful. An undertaking, he says, begins with a surge of energy that carries it a certain distance toward completion. There then occurs a drop in energy, which must be lifted back to an effective level by conscious effort, in my experience by bringing to bear hard purpose. It is here that years of steady application to a specific process can come into play. It is, however, in the final stage, just before completion, that Gurdjieff says pressure mounts almost unendurably to a point at which it is necessary to bring to bear an even more special kind of effort. It is at this point, when idea is on the verge of bursting into physicality, that I find myself meeting maximum difficulty. I sometimes have the curious impression that the physical system seems in its very nature to resist its invasion by idea. The desert wishes to lie in the curves of its own being: It resists the imposition of the straight line across its natural pattern. Matter itself seems to have some mysterious intransigency.

It is at this critical point that most failures seem to me to occur. The energy required to push the original concept into actualization, to finish it, has quite a different qualitative feel from the effort needed to bring it to this point. It is this strange, higher-keyed energy to which I find I have to pay attention—to court, so to speak, by living in a particular way. Years of training build experience capable of holding a process through the second stage. The opposition of purpose to natural indolence, the friction of this opposition, maintained year after year, seems to create a situation that attracts this mysterious third force, the curious fiery energy required to raise an idea into realization. Whether or not it does so attract remains a mystery.

The Baltimore exhibit is in the second stage of this process. We are bringing our experience to it and are prepared to bear down hard through the final stage. Whether the exhibit will lift into the light in which we conceive it to exist remains in jeopardy.

13 JANUARY

The east-west-north-south coordinates, latitude and longitude, of my sculptures exactly reflect my concern with my position in space, my location. This concern, an obsession since earliest childhood, must have been the root of my 1961 decision—taken unconsciously in a wave of conviction so total as to have been unchallenged by logic—to place my sculptures on their own feet as I am on mine. This is a straight, clear line between my life and my work.

14 JANUARY

Yesterday morning I wrote the lecture I am to give at the Baltimore Museum of Art. The shape of my work’s development becomes a little clearer every time I am forced to articulate it. I noticed for the first time yesterday, in reviewing my slides, how rapidly the scale of the earliest work in 1961–62 changed from that of fence to that of human beings, and then to that which comprehended human beings as incidental within its own range.

The Arundel paintings were picked up yesterday afternoon, departing into a twilight dancing with large fluffy snow flakes as white as themselves. No amount of experience seems to dull the prick of separation. Quick, not entertained, but inevitable. Now the paintings are covered with the same quiet attention with which I follow my children in my mind.

15 JANUARY

A day of rest idles my mind into a nullity out of which I am refreshed. Lying under my warm covers, I spent most of yesterday wandering over the Near East with Alexander the Great, conquering my way to the river Hyphasis and turning back toward Macedonia as reluctantly as he did. There is always that wrench, not being able to do it all.

Military tactics interest me very much. Wellington’s choice of ground at Waterloo, his disposition of his forces, his timing, and above all his resolute decision to stand and die or stand and live, brace my heart for lesser battles. Alexander was an inspired tactician. At Jhelum his horses, maddened with fear, refused to advance across a river into King Paros’s elephants, the front line of an army superbly trained and many times the size of Alexander’s. Calmly setting up a pattern of behavior calculated to lead an intelligent observer to conclude that he intended to stand siege on his side of the river until the seasonal waters fell, Alexander seized a night of storm, crossed the river under its thunder and lightning, and stampeded the elephants with rattling Scythian chariots and flights of arrows. Thus freed to use his nimble cavalry, he moved in authoritatively to decimate his enemy. He just plain outthought King Paros. Obviously, he could not have known that he was going to be successful. He simply made as intelligent a plan as he could and then acted on it with all the force at his command. It is said that he always slept well on the eve of battle. His cardinal tactical principle he derived from Epaminondas: “The quickest and most economical way of winning a military decision is to defeat the enemy not at his weakest but at his strongest point.” (Peter Green, Alexander the Great, New York: Praeger, 1970.) Just so have I found that a direct confrontation of difficulties at their worst is the best starting point for action.

17 JANUARY

The Arundel paintings are installed in the Baltimore Museum of Art. An easy installation. We reduced their number to eight and they seemed to place themselves, even to stretch themselves luxuriously once they were hung. I wish I could be as serene as they looked yesterday after we had finished. I can, and I think I do, use my head on the business of exhibiting, but there is an irreducible strain. It is easier than last winter but—I guess because I am trying to do it all more plainly, without excitement—my spirit rises only sluggishly to the challenge.

19 JANUARY

But there are pleasures too in exhibiting. Flowers abound all over the house; friends encircle me. This is the period I always think of as comparable to the protection given an elephant in labor. When, after almost two years of gestation, she is ready to deliver her child, the herd forms a circle around her. A particular friend helps her in her labor and coaxes the baby into vitality. The circle remains intact until the mother and child are ready to travel. Then the herd moves on, larger by one member.

20 JANUARY

The Baltimore exhibit is now open. The reaction was exactly what it always is. Some, most, simply cannot “see” the work at all. One of my children overheard the scornful remark, “Well, I never did think Anne Truitt was much of an artist.”

This failure to see is not only psychological but also can apparently be physical. A physicist explained to me during dinner at the museum last night about the macula lutea, a yellow retinal filter that circumscribes the fovea. Foveal vision, which determines our apprehension of line, is limited by its cellular nature to the perception of red and green only. This perceptive acuity apparently varies little from person to person. The saturation of yellow in the macula lutea, however, varies considerably. It is the nature of this filter that determines our perception of blues. Thus, some people, those with concentrated yellow in the macula lutea, are literally unable to see close changes of hue on the blue end of the spectrum.

I always take off my glasses to mix color. This must be an instinctive shift in attention away from foveal vision, specific and limited to red-green sensitivity, toward a concentration on the entire possible range of subtle hue and value discrimination. In addition, since all glass absorbs blue light, removing my glasses increases the amount of blue light reaching my eyes.

These facts seem to me relevant to the apprehension of the Arundel paintings, which depend for their perception on both foveal and nonfoveal vision. The lines in them are sometimes so widely spaced that they cannot be seen simultaneously, and the fields of white in w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- A new introduction by Audrey Niffenegger

- Dedication

- Preface

- Tucson, Arizona, June 1974

- Yaddo, Saratoga Springs, New York, July–August 1974

- Washington, D.C., August 1974–June 1975

- 1975

- 1978

- 1979

- 1980

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright