- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

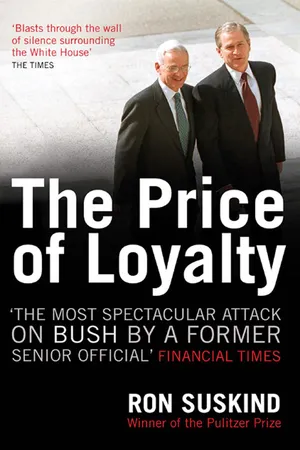

The Price of Loyalty

About this book

A devestating account of the inner workings of the George W. Bush administration, written with the extensive cooperation of former U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill. As readers are taken to the very epicentre of government, this news-making book offers a definitive view of Bush and his closest advisers as they manage crucial domestic policies and global strategies within the most secretive White House of modern times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Price of Loyalty by Ron Suskind in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

FIRST APPOINTMENT

PAUL O’NEILL LOOKED UP from his legal pad and out the window of USAir Flight 991 from Pittsburgh as it made a panoramic descent into Washington’s Reagan National Airport.

God knows how many times he’d traveled this northwesterly arc high across the Potomac, an ideal angle to glimpse the Mall’s Elysian symmetry of white marble and green expanse from the Capitol dome to Lincoln’s Memorial. It still thrilled him, this confected balance, as it had when he arrived as a young, working-class kid, with a wife, two babies, an economics degree from unremarkable Fresno State College, and a few years working as a self-taught engineer. He’d landed a job working in the Veterans Administration by filling out an application for federal internships he’d picked up at the post office. Three hundred thousand applicants went on to take a federal standardized test. Three thousand were summoned for an oral review, where they were interviewed in groups of ten. Three hundred were offered jobs. It was 1961. Kennedy was President. The start of everything, really.

Now, thirty-nine years later, he had reasons, good ones, why he shouldn’t come back. They were on the yellow legal pad, neatly lined and spaced, resting on the tray table. He checked it one last time, a list that covered three handwritten pages, then considered what had been said thus far and what would be expected of him in a few hours at his first meeting with the President-elect.

His old friend Richard Cheney—quiet, poker-faced Dick—had done almost all the talking thus far, starting with a mid-November call to Paul’s cubicle at Alcoa’s headquarters in Pittsburgh. The call was courteous and cool, like Dick. Always holding something back, making you wonder about the interior workings. He’d known the inscrutable westerner since the Nixon days, when O’Neill was assistant director of the newly created Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—a senior management team, of sorts, that Richard Nixon created to solve a growing crisis of scale: the increasing inability of one elected man to make so many complex decisions in a responsible way.

OMB became the stop-and-think shop, where all major issues were studied and distilled into briefs about choices and consequences for the President. It was the spot to be, and O’Neill—nearly a decade in the government at that point—was a rising young man of his day, a budget wizard who became a deep driller on what was known and knowable in a wide array of policies. Dick Cheney was a twenty-eight-year-old Ph.D. student brought into the Office of Economic Opportunity—a policy sidecar headed by an ambitious ex-congressman named Donald Rumsfeld—which was charged with carrying forward Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Rumsfeld, as a department head, was someone an OMB honcho like O’Neill regularly dealt with, and Dick was always at Don’s side. A few years later, when everyone had moved up—Rumsfeld to chief of staff under Gerald Ford, with Dick as his deputy (Cheney took the top staff job when Rumsfeld became Secretary of Defense)—Dick started introducing Paul, then OMB’s deputy director, as “the smartest guy I know.” Still did, or at least so Paul had heard from a few of their mutual friends—they had about a thousand of those.

That first call was just a “heads-up.” Speculation had swirled in the press about O’Neill being tapped for OMB director, for Commerce Secretary, or—in a late October column by The New York Times’s William Safire—for Secretary of Defense. As someone who’d met George W. Bush—although only in passing, and although he’d never contributed to the campaign—O’Neill had managed to surface on plenty of lists. He was viewed as a favorite of the former President Bush, as a serious policy innovator among traditional Republicans, and as someone George W. Bush would need at his side, in some capacity, if he were to become President. That last issue was very much in question in mid-November 2000, as the Florida election results were still in dispute, but Dick wanted to lay down a marker.

“I don’t know how this all will sort out, Paul, but you’re at the top of our list,” Dick had said on the phone.

“That’s very flattering, Dick, but I don’t think I want to go back to the government.”

Dick pressed on, talking in general terms about Commerce or OMB and the challenge of getting talented people to serve. Paul let that sink in for moment and then said, “No, I don’t think so, Dick. But thanks.”

Three weeks later, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in the case of Bush v. Gore. The justices announced on Saturday, December 9, that they would examine the previous day’s ruling by the Florida Supreme Court, which had mandated a manual recount of all ballots cast in the state. The Florida ruling had been a reprieve for the Democrats, the restart of a process that they were sure would level the playing field, with oral arguments on recount procedures scheduled for Monday. But the Supreme Court’s Saturday halt to the recount—essentially taking the issue away from Florida’s courts—shifted the betting line from even money to advantage Bush.

The next afternoon, Sunday, Paul was watching his beloved Pittsburgh Steelers lose 30–10 to the New York Giants, effectively knocking the hometown team out of the playoffs. The phone rang. He jumped up, grabbed it in the kitchen. Dick again.

“Soon I may have to call you Mr. Vice President.”

“Maybe so, Paul. We’ve got our fingers crossed.”

Fine, on to business.

“We really need you here in Washington.”

“Dick, I’m really not interested.”

Then he heard what he thought was Dick’s suppressed, Sydney Greenstreet snigger. “You need to let me tell you it’s Treasury.”

Paul smiled. He could hear Dick smiling on the other end of the phone line. Yes, Treasury is the oldest—the first appointment made by George Washington himself—and the most venerable of the cabinet offices. It was and is a public trust, literally. Alexander Hamilton, one of the great geniuses of his era, sat in the chair first, a special chair.

“Well, yes, I suppose Treasury is a little different. I’ll concede that.” He paused a moment. “Okay, I suppose we can at least talk about Treasury.”

“We’ll be in touch,” Dick said.

Paul hung up the phone and walked back into the living room. His wife, Nancy—levelheaded, resilient Nancy—was on the couch, looking hard at him. The novel she’d been engrossed in was closed on her lap.

“My God, Paul. We are not really going to do this!” she said. “You always said you’re not going back there.”

“Don’t worry, we’re not,” O’Neill said, and sat back down in the lounge chair. “Don’t worry.” He flipped to CNBC. He could feel Nancy still staring at him. He had been excited to hear Dick’s voice—he was sure she could pick that up, even from a room away. It was flattering, after all, to be asked. Especially about something as august as Treasury.

“Right,” she said more softly, after a moment. “Hurry up and get down here so everyone can kick you around. Everything has become so nasty down there now. Come on, honey. You’re not a politician. You know what it’d be like.”

After forty-five years of marriage, they both knew everything. They’d been together, after all, since they were eighteen. Grew up together. A pair of small-town kids, made good. Paul was never the kind of American achiever who believed he was evolving, anxious thereby to match each success with fresh start accoutrements like new wives and dazzling possessions. Neither of them, in fact, felt they’d changed all that much since she saw him walk into her English class senior year at Anchorage High School in Alaska, the new boy who lived out on the military base. Yes, she’d since read press clippings that said he was God’s gift to corporate America, or a messiah of good government, but to her he was just Paul, gentle, quirky, polite, loyal to a fault when that loyalty is earned, and if he were a garbage collector or doing construction in Alaska—his career choice before he chanced into the Claremont, California, Post Office—she’d still be at his side.

Not that there hadn’t been struggles, as in any marriage, and, God knows, sacrifices. Plenty on Nancy’s end. During the sixteen years in Washington—most of their first two decades together—she raised their three daughters and son by herself. Paul worked nearly seven days a week, seventeen hours a day, at a salary that went from subsistence to barely adequate. At the beginning, they couldn’t even afford a phone. She made the kids’ clothing herself. He loved to work; some men do. As he hit his stride in those seven years at OMB, he worked every day but Christmas and a short summer vacation. Things changed a bit after Gerald Ford lost and Paul took an executive job in 1977 at International Paper Company in New York City—at least there was money. That helped some; they started to enjoy a few of the rewards. Pittsburgh, though, had been their best stop: thirteen years at Alcoa, where Nancy built a life around Paul’s blossoming success—scores of friends, leading roles in the community for them both—even while his days were still long, scheduled to the minute, and took him out of town, on average, once or twice a week. It was an extraordinary run, a legendary turnaround: a battered and beaten Aluminum Company of America went from $1.1 million in earnings, on sales of $8 billion, when Paul took over in 1987, to $1.5 billion in earnings, on sales of $23 billion in 2000, a year when Alcoa—now the world’s largest aluminum producer—was the New York Stock Exchange’s best-performing stock. Clean victories on every front. And soon, he’d go out on top. He had passed the CEO’s job on to his handpicked successor in 1999. As for the chairmanship, he was due to retire at the end of this very month.

Just twenty-one days! There were already plans galore, curtain-raisers on a long-awaited valedictory chapter of their lives, with $60 million in the bank and, soon, all the time in the world. In an office nook off the kitchen, Nancy had a folder with maps and brochures for a once-in-a-lifetime journey across America, just the two of them. They were going to spend months driving across America’s back roads. Paul had even picked out the car. They’d drive the blue highways in a Bentley.

Nancy turned back to her novel. Paul switched to football highlights. He’s not going to do it, she thought to herself. He just wouldn’t.

A week later, Paul silently gathered papers and his briefcase and slipped into his black cashmere overcoat on a snowy, dark Monday morning. He’s an early riser, up at 5 a.m. most days and gone by 6. Nancy will usually sleep to a sane hour, seven o’clock or so. But not this morning.

She appeared in her pink satin bathrobe, her bare feet lightly clapping across the kitchen’s Italian tile floor.

He turned, surprised.

“You’re up early.”

“I wanted to see you off.”

Of course, Paul could figure out why she was padding about in darkness. “Listen, I’m just going down there to talk about it. It’s a joint decision. We’ll decide together.”

She knew this was trouble. He was going to see Dick and the President-elect. They’d be persuasive. They’d say whatever he wanted to hear.

“Don’t you go down there and tell them you’re going to do it.”

“Don’t worry.” He kissed her. “You know me better than that.”

· · ·

A LIGHT RAIN fell in Washington on December 18, 2000, President-elect George W. Bush’s first morning in Washington. The dam of Florida press conferences and hanging chads, a prim, pained Supreme Court ruling, and an Al Gore concession of unexpected grace was beginning to recede beneath a quotidian tide of news cycles.

Every hour was being covered as an event, as an onrushing measure of forward motion. The President-elect’s first date, at 8 a.m., was an hour-long breakfast meeting with Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan at the Madison Hotel—about five blocks from the White House—where Bush was staying in a suite and holding court. It was followed by a brief press advisory at the hotel, where he said, “I talked with a good man right here.” He then turned to Mr. Greenspan and patted him on the shoulder. “We had a very strong discussion about my confidence in his abilities.”

Next stop, Capitol Hill, for a two-and-a-half-hour meeting with congressional leaders from each party, followed by a press availability in a chandeliered, wood-paneled, squash court–size room on the second floor of the Capitol. The President-elect stood on a threadbare Oriental rug beneath a life-size painting of George Washington and spoke like a therapist after a successful session.

“I made my rounds to the leaders here on the Hill,” Bush said, standing shoulder to shoulder with his four conferees of midmorning: Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott and Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle; House Speaker Dennis Hastert and House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt, a barbershop quartet of bipartisanship. “I want to thank all four for their hospitality and their gracious reception of the newly elected President. I made it clear to each that I come to Washington with the intention of doing the people’s business, that I look forward to listening and occasionally talking, to work with both the Republicans and the Democrats.”

Bush paused and looked side to side, as though he might call for a group hug.

“I told all four that I felt like this election happened for a reason”—reporters hung on the word “reason,” a natural segue to the thing they were waiting for: an assessment of how the brokered, litigated presidential election would now define the act of governing—“that it pointed out the delay in the outcome. It should make it clear to all of us that we can come together to heal whatever wounds may exist, whatever residuals there may be.”

Bush dodged it—the what-exactly-is-my-mandate-now issue—but this “heal whatever wounds may exist” line, it was instantly clear, would be the day’s lead quotation on television and radio and in tomorrow’s newspapers.

“I told all four that there are going to be some times where we don’t agree with each other, but that’s okay. If this were a dictatorship, it would be a heck of a lot easier, just so long as I’m the dictator.”

That capped it: a startling turn of self-deprecation and bluster from a man who shrugged at questions of his legitimacy. The disputed, dead-heat election of 2000—concluding a presidential contest in which both candidates sanded off their sharp edges in a race for the political center—had finally delivered a historically half-hearted mandate: a charge that solutions in the coming months, of whatever shape or color, were expected to be unearthed from middle ground. A fifty-fifty split in the Senate, a modest, nine-vote Republican advantage in the House, and a President who assumed office after losing the popular vote meant that the public’s grant of power was almost legally conditioned on the centrist ideal. The President, after all, is the principal elected representative of all the people. The vox populi, in sum, spelled middle.

The only dissonant chord was at that point barely audible, a comment the day before by Dick Cheney on CBS’s Face the Nation: “As President-elect Bush has made very clear, he ran on a particular platform that was very carefully developed; it’s his program and it’s his agenda and we have no intention at all of backing off of it. . . . The suggestion that somehow, because this was a close election, we should fundamentally change our beliefs I just think is silly.”

To be sure, that was a kind of pregame interview, the day before George W. Bush arrived in town. When the President-elect spoke this morning, backed by congressional leaders of both parties, it carried the weight of authority. A commitment to the humble search for common ground.

After fielding a few questions from reporters, Bush gazed at the bipartisan assemblage and said, somewhat dreamily, “It’s amazing what happens when you listen to the other person’s opinion. And we began the process of doing that today.”

· · ·

THIS ECUMENICAL IDEAL—as of this morn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Half-title page

- Also by Ron Suskind

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Author’s Note

- Dedication page

- Epigraph page

- Contents

- CHAPTER 1 FIRST APPOINTMENT

- CHAPTER 2 A WAY TO DO IT

- CHAPTER 3 NO FINGERPRINTS

- CHAPTER 4 BASE ELEMENTS

- CHAPTER 5 THE SCALE OF TRAGEDY

- CHAPTER 6 THE RIGHT THING

- CHAPTER 7 A REAL CULT FOLLOWING

- CHAPTER 8 STICK TO PRINCIPLE

- CHAPTER 9 A TOUGH TOWN

- EPILOGUE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INDEX

- About the Author