- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Palladio is the Bible," Thomas Jefferson once said. "You should get it and stick to it." With his simple, gracious, perfectly proportioned villas, Andrea Palladio elevated the architecture of the private house into an art form during the late sixteenth century -- and his influence is still evident in the ample porches, columned porticoes, grand ceilings, and front-door pediments of America today.

In The Perfect House, bestselling author Witold Rybczynski, whose previous books (Home, A Clearing in the Distance, Now I Sit Me Down) have transformed our understanding of domestic architecture, reveals how a handful of Palladio's houses in an obscure corner of the Venetian Republic should have made their presence felt hundreds of years later and halfway across the globe. More than just a study of one of history's seminal architectural figures, The Perfect House reflects Rybczynski's enormous admiration for his subject and provides a new way of looking at the special landscapes we call "home" in the modern world.

In The Perfect House, bestselling author Witold Rybczynski, whose previous books (Home, A Clearing in the Distance, Now I Sit Me Down) have transformed our understanding of domestic architecture, reveals how a handful of Palladio's houses in an obscure corner of the Venetian Republic should have made their presence felt hundreds of years later and halfway across the globe. More than just a study of one of history's seminal architectural figures, The Perfect House reflects Rybczynski's enormous admiration for his subject and provides a new way of looking at the special landscapes we call "home" in the modern world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Perfect House by Witold Rybczynski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Godi

After an excessive meal, which raises again the puzzle of how Italians get anything done in the afternoon, I take a stroll. The restaurant is on the outskirts of the village. The houses here are too new to be picturesque, but the neat buildings and well-kept gardens attest to the prosperity of the region. The suburban landscape is dotted with agricultural remnants: a renovated farmhouse, a stone barn, a fenced piece of pasture. At the edge of the built-up area the ground rises steeply and I can see the bare branches of an orchard. Farther up the hill, behind a forsythia hedge that is already blooming, a large rectangular building with a red-tile roof commands the scene. This is what I’ve come to see—Palladio’s Villa Godi. Although Renaissance country houses are commonly referred to as villas, this use of the term is modern. In the sixteenth century, la villa referred to the entire estate; the house itself was la casa padronale (the master’s house), or more simply la casa di villa.

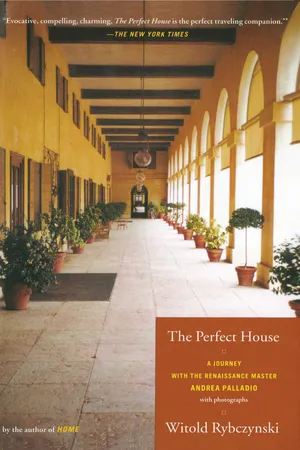

I drive my rented car up the winding road. “Placed on a hill with a wonderful view and beside a river” is how Palladio described the house, and despite its industrial excrescence the Astico valley still presents a spectacular vista.1 The house sits on a man-made podium circumscribed by an imposing stone retaining wall. The curving, battered wall resembles a medieval bastion; the sturdy building, with its compact mass and severe symmetry, likewise has a military bearing. At first glance it could be an armory or a garrison post. As one gets closer, two features soften its severity: the plastered walls, which are painted a faded but cheerful buttery yellow and resemble old parchment, and an arcaded loggia, which is recessed into the center of the building and creates a shaded and welcoming entrance.

The caretaker lets me in through a large wrought-iron gate and I follow a path across the podium. The gravel crunches agreeably underfoot. The lawn is planted with conifers clipped into spheres and pyramids. A fountain, whose centerpiece is a statue of a nymph surrounded by cavorting cherubs, sprays water into a pool. I give her a sideward glance and hurry through the garden to the house.

VILLA GODI

The villa, which did not look large from a distance, turns out to be immense, almost as tall as a modern five-story building. The plain plastered walls are relieved by a regular pattern of windows with stone frames and slightly different details: a heavy bracketed sill for the lowest floor; a delicately modeled sill for the main level; and a plain surround for the attic. Square windows are pushed up against an elegant cornice just under the shallow eaves. The cornice is supported by a row of little repetitive blocks, a detail adapted from ancient Roman temple eaves decorations called modillions. These are the only classical references in this otherwise undecorated and austere façade.

“The master’s rooms, which have floors thirteen feet above ground, are provided with ceilings,” Palladio wrote, “above these are the granaries, and in the thirteen-foot-high basement are placed the cellars, the places for making wine, the kitchen, and other similar rooms.”2 This pragmatic stacking of warehouse and domestic uses originated in Venice, where land was scarce.3 The tall Godi “basement” is entirely aboveground, so a long straight stair leads to the loggia. This spacious outdoor room faces west, which must give splendid views of sunsets over the peaks of the altipiano but leaves the main façade of the house exposed to the hot afternoon sun. It is unclear why Palladio turned the building this way—the preferred orientation was southern, and that view was equally fine. It may have had to do with how one originally arrived at the villa, since old maps show a long, straight approach road climbing the hill from the west. Or it may be explained by the fact that the villa is believed to incorporate parts of a medieval house that already existed on the site.4 The citizens of the Venetian Republic had a reputation for penny-pinching, if not outright parsimony, and new houses were frequently built on top of old ones in order to save money by reusing foundations and walls.

The intonaco, or plastered stucco, of the walls shows marks where it was once incised to simulate the joints of stone construction. The entry in my old edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica claims that Palladio’s buildings were originally “designed to be executed in stone.”5 In fact, none of Palladio’s country houses are built of stone; all are brick covered in plaster, which was the standard method of construction for rural buildings. The jointing pattern, which is faint today but was prominent when the house was built, was not meant to deceive. Like the wooden faux-stonework of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, it produces a sense of scale as well as a pleasing decorative texture.

Not all the masonry is simulated. The most distinctive feature of the house is the three-arch loggia whose square piers, arches, and imposts from which the arches spring are all faced with stone. Two carved stone emblems adorn the wall above the loggia: an armorial shield with imperial eagles, symbols of the owner’s nobility, and a rampant lion, the stemma, or coat of arms, of the Godi family. An inscription on the tablet below reads HIERONYMUS GODUS HENRICI ANTONII FILIUS FECIT ANNO MDXLII (Built by Girolamo Godi, son of Enrico Antonio, in the year 1542). The Godis, one of the most powerful and wealthy patrician families of Vicenza, owned large estates in the Vicentino. When the patriarch Enrico Antonio died in 1536, he bequeathed the lands in common to his three sons (the fourth was a priest). Girolamo took charge of the Lugo holdings, more than five hundred acres, which included the hilltop of Lonedo, where he started to build a villa the following year.

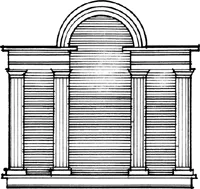

Small doors lead directly from the loggia to rooms on either side, but the large door in the center is obviously the main entrance. PROCUL ESTE PROFANI is carved into the stone frame. “Keep the unholy far away” may have been intended tongue in cheek, since the Godis were known to have had heretical tendencies. ET LIBERA NOS A MALO—“And deliver us from evil”—completes the sentiment on the inside. I read the interior inscription later, for when I open the door my attention is immediately arrested by the grand space—as Palladio, no doubt, intended. The cavernous room rises up to the roof—about twenty-five feet—and extends all the way to the rear of the house. This is the sala, or hall. The sala, which originated in medieval times, was a common feature of Venetian country houses. Always the largest room in the house, it was neither an entrance vestibule nor a living room, but a formal social space, “designed for parties, banquets, as the sets for acting out comedies, weddings, and similar entertainments,” Palladio wrote.6 The sala in the Villa Godi is lit by a large window, a triple opening with a semicircular arch in the center called a serliana.I This end of the sala extends slightly beyond the rest of the house, and the additional narrow windows on the two sides give the effect of a large bay window, which not only illuminates the room but also affords views of the garden below.

The sala is flanked by eight large rooms—four on each side. Six of the rooms are identical, two are slightly smaller to make room for the staircases; the large rooms are each about eighteen by twenty-eight feet. This seems like a lot of space, but the bachelor Girolamo shared the villa with his brothers and their families. There are no corridors; instead, each room opens directly into the next. The doors and windows are exactly lined up so that standing in one of the rooms with my back to a window, I can look through four sets of open doors and see the corresponding window on the opposite side of the house. The stair, the loggia arcade, the front door, the sala, and the serliana are likewise carefully aligned. These precise geometrical relationships give the interior a sense of calm and repose. Everything appears in its place.

I walk around the house, or rather slide since I am obliged to wear felt slippers to reduce wear on the floors. These are battuto, an early version of terrazzo, made by slathering a mixture of lime, sand, and powdered brick across the floor, pressing milled stone chips into the hardening mixture with heavy rollers, then grinding smooth and oiling the surface. There are no other visitors, and the caretaker has left me alone. I swish from room to room. The doorways are low and the unpretentious doors of simple plank construction have wrought-iron strap hinges. The identical windows incorporate a charming feature: facing stone seats that transform them into little conversation nooks. The flat ceilings are supported by closely spaced wooden beams with ornamental carvings on the underside. The only room with a plaster ceiling is in the southeast corner of the house, a privileged position that gets the morning sun, summer and winter, and probably belonged to Girolamo.

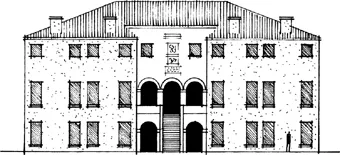

SERLIANA, OR PALLADIAN WINDOW

The Godi house, which was begun about 1537, has the distinction of being Palladio’s first villa; indeed, as far as we know, it was his first independent commission. The novice had moments of clumsiness, particularly in the front façade. The recessed entrance bay, for example, while welcoming, has a large section of blank wall over the loggia, which the heraldic coats of arms do not quite fill. The external staircase rises to a complicated landing in front of the loggia that distracts from the overall composition. The asymmetrical placement of the windows on the façade is disturbing. Instead of being equally spaced they are bunched together in pairs (to leave space for the fireplaces and chimneys, which are located on the exterior walls). Thirty years later, when Palladio was writing his architectural treatise, he included drawings of the Villa Godi but took the opportunity to smooth out these defects. Leaving the plan largely unaltered, he simplified the stair, reduced the number of windows and spaced them equally, and capped the central section of the house with a pediment.

The design of the villa is very successful in one key respect. Earlier Venetian villas often look like town houses transposed to the country, elegant but slightly ill at ease. Palladio manages to make the Godi both a polished work of architecture and a sturdy farmhouse. Like a country gentleman in a tailored hacking coat and muddy rubber boots, the villa fits into its surroundings, even as it holds itself above them. This quality would permeate all of Palladio’s villas, which are both sophisticated and rustic, genteel and rude, cosmopolitan and vernacular.

The Villa Godi hasn’t always been appreciated. Sir Charles Barry, the leading British architect of the early 1800s, thought it “an unarchitectural pile.”7 Banister Fletcher, the nineteenth-century author of a long-lived architectural history, a bulky copy of which I owned as a student, considered the Godi’s main façade “a very poor example of our master’s genius.”8 The modern art historian Rudolf Wittkower criticized the Villa Godi as “retrogressive.”9 Indeed, as Wittkower pointed out, the design bears a resemblance to the Villa Tiretta, a country house built about forty years earlier near the village of Arcade, only thirty miles away.10 In fact, the proportions of Godi are more robust than Tiretta, and the massing is much more accomplished. But the resemblance is a reminder that Palladio, at this early stage of his career, was not straying far from established local traditions. His conservatism is understandable. Most architects today begin their careers designing kitchen additions or weekend cottages. The Godi is a palatial residence on a dramatic site, for the richest family in town. A mistake here could stop one’s career in its tracks; it is prudent to be cautious.

THE RAISED LOGGIA, WITH ITS THREE ROMAN ARCHES, MARKS THE ENTRANCE TO THE VILLA GODI.

An architect’s early work is often consigned to a back drawer. Some masters, such as Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, even suppressed their youthful efforts. Yet when the elderly Palladio was being interviewed by the painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, who was collecting material for Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, he specifically mentioned the Villa Godi.11 And he included a description of the villa in his great treatise, I quattro libri dell’architettura (The four books on architecture), which he published near the end of his life. He may have made some mistakes and not broken new ground at the Villa Godi, but he was obviously proud of his first building. It couldn’t have been an easy commission: a no-doubt demanding client used to getting his own way; an exceptionally large house; a dramatic site with a splendid view, but also perched on a slope and restricted in area; and existing buildings that had to be integrated into the design. Yet the novice pulled it all together and produced a handsome work of great gravitas and, yes, nobility. It is an exceptional accomplishment for a beginner.

• • •

A beginner in architecture but no stripling, for when Palladio was first mentioned as working on the Godi house he was already thirty-two years old. Renaissance architectural careers started late: Filippo Brunelleschi was forty-one when he entered the competition to design the dome of the cathedral in Florence; the great Donato Bramante was thirty-seven when he was called to rebuild St. Peter’s in Rome; Vasari was forty when h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Foreword

- Chapter I: Godi

- Chapter II: Che Bella Casa

- Chapter III: The Arched Device

- Chapter IV: On the Brenta

- Chapter V: Porticoes

- Chapter VI: The Brothers Barbaro

- Chapter VII: An Immensely Pleasing Sight

- Chapter VIII: Emo

- Chapter IX: The Last Villa

- Chapter X: Palladio’s Secret

- Afterword

- The Villas

- Glossary

- Acknowledgments

- About Witold Rybczynski

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright