- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

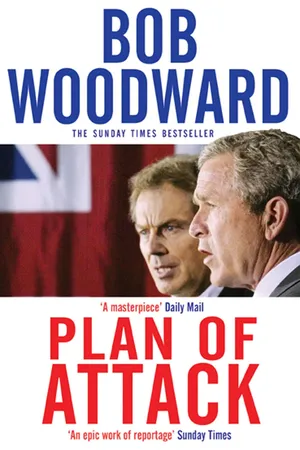

Plan of Attack

About this book

Award-winning journalist Bob Woodward has spent over thirty years in Washington's corridors of power. In All the President's Men it was he, together with Carl Bernstein, who exposed the Watergate scandal and he has been giving us a privileged front-row seat to White-House intrigue and decision-making ever since.

With PLAN OF ATTACK he brings his investigative skills to bear on the administration of George W. Bush, and the build-up to war in Iraq. What emerges is a fascinating and intimate portrait of the leading powers in Bush's war council and their allies overseas as they prepare their pre-emptive attack and change the course of history.

With PLAN OF ATTACK he brings his investigative skills to bear on the administration of George W. Bush, and the build-up to war in Iraq. What emerges is a fascinating and intimate portrait of the leading powers in Bush's war council and their allies overseas as they prepare their pre-emptive attack and change the course of history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

IN EARLY JANUARY 2001, before George W. Bush was inaugurated, Vice President–elect Dick Cheney passed a message to the outgoing secretary of defense, William S. Cohen, a moderate Republican who served in the Democratic Clinton administration.

“We really need to get the president-elect briefed up on some things,” Cheney said, adding that he wanted a serious “discussion about Iraq and different options.” The president-elect should not be given the routine, canned, round-the-world tour normally given incoming presidents. Topic A should be Iraq. Cheney had been secretary of defense during George H. W. Bush’s presidency, which included the 1991 Gulf War, and he harbored a deep sense of unfinished business about Iraq. In addition, Iraq was the only country the United States regularly, if intermittently, bombed these days.

The U.S. military had been engaged in a frustrating low-grade, undeclared war with Iraq since the Gulf War when Bush’s father and a United Nations–backed coalition had ousted Saddam Hussein and his army from Kuwait after they had invaded that country. The United States enforced two designated no-fly zones, meaning the Iraqis could fly neither planes nor helicopters in these areas, which comprised about 60 percent of the country. Cheney wanted to make sure Bush understood the military and other issues in this potential tinderbox.

Another element was the standing policy inherited from the Clinton administration. Though not widely understood, the baseline policy was clearly “regime change.” A 1998 law passed by Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton authorized up to $97 million in military assistance to Iraqi opposition forces “to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein” and “promote the emergence of a democratic government.”

On Wednesday morning, January 10, ten days before the inauguration, Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice and the designated secretary of state, Colin L. Powell, went to the Pentagon to meet with Cohen. Afterward, Bush and his team went downstairs to the Tank, the secure domain and meeting room for the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Bush sauntered in like Cool Hand Luke, flapping his arms slightly, cocky but seeming also ill at ease.

Two generals briefed them on the state of the no-fly zone enforcement. Operation Northern Watch enforced the no-fly zone in the northernmost 10 percent of Iraq to protect the minority Kurds. Some 50 U.S. and United Kingdom aircraft had patrolled the restricted airspace on 164 days of the previous year. In nearly every mission they had been fired on or threatened by the Iraqi air defense system, including surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). U.S. aircraft had fired back or dropped hundreds of missiles and bombs on the Iraqis, mostly at antiaircraft artillery.

In Operation Southern Watch, the larger of the two, the U.S. patrolled almost the entire southern half of Iraq up to the outskirts of the Baghdad suburbs. Pilots overflying the region had entered Iraqi airspace an incredible 150,000 times in the last decade, nearly 10,000 in the last year. In hundreds of attacks not a single U.S. pilot had been lost.

The Pentagon had five graduated response options when Iraqis fired on a U.S. aircraft. Air strike counterattacks were automatic; the most serious ones, involving multiple strikes against more important targets or sites outside the no-fly zones, required notification or direct approval of the president. No-fly zone enforcement was dangerous and expensive. Multimillion-dollar jets were put at risk bombing 57-millimeter antiaircraft guns. Saddam had warehouses of them. As a matter of policy, was the Bush administration going to keep poking Saddam in the chest? Was there a national strategy behind this or was it just a static tit-for-tat?

An operation plan called Desert Badger was the response if a U.S. pilot were to be shot down. It was designed to disrupt the Iraqis’ ability to capture the pilot by attacking Saddam’s command and control in downtown Baghdad. It included an escalating attack if a U.S. pilot were captured. Another operation plan called Desert Thunder was the response if the Iraqis attacked the Kurds in the north.

Lots of acronyms and program names were thrown around— most of them familiar to Cheney, Rumsfeld and Powell, who had spent 35 years in the Army and been chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1989 to 1993.

President-elect Bush asked some practical questions about how things worked, but he did not offer nor hint at his desires.

The JCS staff had placed a peppermint at each place. Bush unwrapped his and popped it into his mouth. Later he eyed Cohen’s mint and flashed a pantomime query, Do you want that? Cohen signaled no, so Bush reached over and took it. Near the end of the hour-and-a-quarter briefing, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Army General Henry “Hugh” Shelton, noticed Bush eyeing his mint, so he passed it over.

Cheney listened but he was tired and closed his eyes, conspicuously nodding off several times. Rumsfeld, who was sitting at a far end of the table, paid close attention though he kept asking the briefers to please speak up, or please speak louder.

“We’re off to a great start,” one of the chiefs commented privately to a colleague after the session. “The vice president fell asleep and the secretary of defense can’t hear.”

Cohen, who was leaving the Defense Department in 10 days, believed that the new administration would soon see the reality about Iraq. They would not find much, if any, support among other countries in the region or the world for strong action against Saddam, which would mean going it alone in any large-scale attack. What could they accomplish with air strikes? Not much, he thought. Iraq was treacherous. When everything was weighed, Cohen predicted the new team would soon back off and find “reconciliation” with Saddam, who he felt was effectively contained and isolated.

In interviews nearly three years later, Bush said of the pre-9/11 situation, “I was not happy with our policy.” It wasn’t having much impact on changing Saddam’s behavior or toppling him. “Prior to September 11, however, a president could see a threat and contain it or deal with it in a variety of ways without fear of that threat materializing on our own soil.” Saddam was not yet a top priority.

BUSH RECEIVED A SECOND critical national security briefing a few days later. CIA Director George Tenet and his deputy for operations, James L. Pavitt, gave Bush, Cheney and Rice the so-called secrets briefing. For two and one-half hours, the two ran through the good, bad and ugly about covert operations, the latest technical surveillance and eavesdropping, the “who” and “how” of the secret payroll.

When all the intelligence was sorted, weighed and analyzed, Tenet and Pavitt agreed there were three major threats to American national security. One was Osama bin Laden and his al Qaeda terrorist network, which operated out of a sanctuary in Afghanistan. Bin Laden terrorism was a “tremendous threat” which had to be considered “immediate,” they said. There was no doubt that bin Laden was going to strike at United States interests in some form. It was not clear when, where, by what means. President Clinton had authorized the CIA in five separate intelligence orders to try to disrupt and destroy al Qaeda.

A second major threat was the increasing proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, WMD—chemical, biological and nuclear. This was of immense concern, they said. Third was the rise of China, especially its military, but that problem was 5 to 15 or more years away.

Iraq was barely mentioned. Tenet did not have an agenda for Iraq as he did for bin Laden and al Qaeda.

On the 17th day of the Bush presidency, Monday, February 5, Rice chaired a principals committee meeting that included Cheney, Powell and Rumsfeld. Deputy CIA Director John E. McLaughlin substituted for Tenet. The purpose was to review Iraq policy, the status of diplomatic, military and covert options. Among the first taskings were for each principal and his department or agency to examine and consider how intelligence collection could be increased on Iraq’s suspected weapons of mass destruction.

At least on paper, the United Nations had an economic sanctions policy directed at Saddam’s regime. The principals conceded that Saddam had basically won the public relations argument by convincing the international community that the sanctions were impoverishing his people, and that they were not stopping him from spending money to keep himself in power.

Powell very quickly said they needed to attempt to get the U.N. to revise the sanctions to tighten them on material that might advance Saddam’s military and WMD programs. Sanctions could then be eased on civilian goods.

Another issue was the weapons inspections inside Iraq that the U.N. had authorized after the Gulf War to establish that Saddam no longer possessed weapons of mass destruction. The inspectors had helped to dismantle Iraq’s chemical, biological and surprisingly advanced nuclear programs, but suspicious accounting of destroyed munitions and elaborate concealment mechanisms left many unanswered questions. In 1998 Saddam had forced the inspectors out, and the question was what might be done to get them back in. No one had a good answer.

What should be the approach to Iraqi opposition groups both outside and inside Iraq? When should weapons and other lethal assistance be provided? Who should provide it—the CIA or Defense? Again no one had a complete answer.

Rice asked for a review of the no-fly zones. What was their purpose? What were the costs and risks? The benefits?

Bush himself worried about the no-fly zone enforcement. The odds of Iraq getting lucky and downing a pilot were bound to catch up with them. He later recalled, “I instructed the secretary of defense to go back and develop a more robust option in case we really needed to put some serious weapons on Iraq in order to free a pilot.”

The eventual result was a plan to fly fewer sorties and fly them less predictably to enhance the safety of the pilots. If a plane was shot at, the response would be more strategic, hitting Iraqi military installations important to Saddam.

ON FRIDAY, February 16, two dozen U.S. and British bombers struck some 20 radar and command centers inside Iraq, some only miles from the outer areas of Baghdad. A general from the Joint Staff had briefed Rice beforehand and she in turn had informed the president, saying that Saddam was on the verge of linking some key command and control sites with hard-to-hit underground fiber optic cables. They would be destroyed before they were completed. The attacks would be part of the routine enforcement of the no-fly zones. It was the largest strike in two years.

Somehow no one at the Pentagon or the White House had thought to make sure that Rumsfeld was fully in the loop. In the first month, his front office was not yet organized—“complete and total disarray” in the words of one White House official. His deputy and other top Defense civilian posts had not been filled or confirmed. Within the Pentagon there also had not been adequate appreciation of the location of one of the sites near Baghdad. Saddam or his security apparatus had panicked, thinking the United States had launched a larger attack. Air raid sirens went off in Baghdad, briefly putting Saddam on CNN, and reminding the White House and the Pentagon that Saddam had a vote in these shoot-outs: He could respond or escalate.

Rumsfeld, furious, declared that the chain of command had been subverted. By law, military command ran from the president to him as secretary of defense to General Franks at CENTCOM. The Joint Chiefs’ role, again by law, was advice, communications and oversight. He should be the one to deal with the White House and the president on operational matters. Period. “I’m the secretary of defense,” he reminded one officer. “I’m in the chain of command.”

ON MARCH 1, the principals met again and Powell was given the task of devising a plan and strategy to refocus the U.N. economic sanctions on weapons control. Powell knew that the French and Russians, who had substantial business interests in Iraq, were doing everything possible to pull the sanctions apart, get Iraq declared in compliance, and have the sanctions lifted. On the opposite side, the Pentagon did not want anything changed or eased. Rumsfeld and others from Defense repeatedly voiced concern about dual-use items—equipment that might seem innocent but could be used or converted to assist Iraq’s weapons programs.

Look what they are buying, Rumsfeld complained to Powell at one point. They are buying these dumptrucks. They can take off the hydraulic cylinder that pushes the truck bed up and they can use it for a launcher for a rocket. You want to sell them the means to erect rockets to shoot at us or Israel?

For Christ’s sake, Powell said, if somebody wants a cylinder to erect a rocket, they don’t have to buy a $200,000 dumptruck to get one!

Another issue for Rumsfeld was the so-called HET—Heavy Equipment Transporters—that the Iraqis were buying. These are trailers heavy enough to carry a tank. Intelligence had some overhead photography showing the Iraqis were reinforcing some of the transporters, leading to the conclusion that revised sanctions would allow clandestine development of a fleet of tank transporters. To Powell, it seemed that Rumsfeld was suggesting that the Middle East might be overrun by Iraqi tanks.

“Come on!” Powell said. He had become increasingly skeptical. There was a heated fight that led to some of the most bizarre debates he had within the administration.

Rumsfeld also complained about the no-fly zones. Iraqis were shooting at our planes routinely. Where else in our history have we ever let people shoot at us like that? he wanted to know.

What’s the alternative? Powell asked. What did he want? No one ever came up with a viable alternative. Rumsfeld continued to express his discontent, finally saying that the administration was playing “patty-cake.”

Okay, what do you want to play? Powell asked. The discussions moved on to the president’s request for a better military plan in the event that a pilot was shot down. Was there a “big bang” that would deter Iraq from shooting at our pilots? Was there a way to have strategic impact which might both weaken the regime and send a message of seriousness to Saddam?

A formal alternative was not forthcoming.

IT WAS UNPRECEDENTED for someone who had served as secretary of defense—or for that matter any top cabinet post—to come back 25 years later to the same job. It was a chance to play the hand again. Rumsfeld was determined to play it better.

For a whole series of reasons—some that went back decades, some only months—Rumsfeld was going to push hard. Perhaps pushing was an understatement. Rumsfeld not only preferred clarity and order, he insisted on them. That meant personally managing process, knowing all the details, asking the questions, shaping the presidential briefings and the ultimate results. The questions always before him were: What did the president need to know and what could the president expect his secretary of defense to know? In other words, Rumsfeld wanted near-total control.

In part, this desire stemmed from his experience and deep frustrations from 1975–76 when he had been President Gerald Ford’s defense secretary. Rumsfeld was secretary for only 14 months because Ford did not win election in his own right in 1976. Only 44 at the time, he had found the Pentagon difficult and almost unmanageable.

In 1989, some 12 years after leaving the Pentagon, Rumsfeld reflected on the frequent impossibilities of the job during a dinner he and I had at my house. I was writing a book on the Pentagon, and was interviewing all the former secretaries of defense and other top military leaders. The Princeton wrestler had not mellowed. It was just ten days before the presidential inauguration of his longtime GOP rival, George H. W. Bush. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rumsfeld had been a Republican star and a good number in the party, including Rumsfeld, thought he might be president one day. Rumsfeld thought Bush senior was weak, lacking in substance, that he had defined his political persona as someone who was around and available. That night as the two of us ate in my kitchen, he showed no bitterness, perhaps only a sense of lost opportunity. The business was the Pentagon and he stuck to it.

The job of secretary of defense was “ambiguous,” Rumsfeld said, because there was only “a thin layer of civilian control.” He said it was “like having an electric appliance in one hand and the plug in the other and you are running around trying to find a place to put it in.” He added, “You can’t make a deal that sticks. No one can deliver anything more than their temporary viewpoint.” Even the secretary.

There was never enough time to understand the big problems, he said, adding that the Pentagon was set up to handle peacetime issues, such as the political decision about moving an aircraft carrier. In a real war these would be military questions, and he went so far as to say that in case of war the country would almost need a different organization than the Pentagon.

Rumsfeld recalled how the top senior civilian and military officials, some 15, had come into his Pentagon office about 6:30 one night. They needed a decision on which tank the Army should buy. The choices were the one with the Chrysler engine or the one with the General Motors engine. You’ve got to decide, they told him, we can’t. A press release with the announcement was all ready to go with blanks to be filled in with his decision. By his own description, Rumsfeld began flying around his office, telling them they all ought to be “hung by their thumbs and balls.” His voice rising, he had shouted, “You idiots, jerks!” They were not thinking—they would wind up getting neither tank from Congress because “THE BUILDING IS DIVIDED!” Congress would inevitably learn of the divisions. So he refused to decide and the press release was abandoned. It took another three months, but he forced them to reach a decision “unanimously.”

“If someone does not know how to wrestle he will get hurt. If you don’t know how to move, you will get a black eye. Same in Defense,” he said.

RUMSFELD HAD WORKED HARD behind the scenes on the Bush campaign in 2000 on substantive matters, and was at first interested in becoming CIA director in a new administration, having concluded that intelligence was what needed fixing. He had spoken with his onetime aide and friend Ken Adelman, who had been head of arms control in the Reagan administration. Adelman told Rumsfeld bluntly that the CIA would be the wrong job. “It’s a mean place and they eat their own,” he said. “Secondly, I think it is just totally unrealistic. Let me paint you a picture. You’re in the Situation Room and you are going to sit there and say well, here our intelligence shows this and shows that but I’m not going to tell you any policy recommendation.” The CIA director is supposed to stay out of policy. “You are just so out the ass. You can fool other people but that’s not you, it’ll...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- A Note to Readers

- Prologue

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About The Author

- Footnote

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Plan of Attack by Bob Woodward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.