![]()

PART I

UNDERSTANDING

MARKET ORIENTATION

![]()

Chapter One

What It Means to Be Market Driven

First Direct was the world’s leading telephone-only bank, and the fastest growing bank in Britain during the 1990s. It had overcome the notorious inertia of the retail customers of the four big chartered banks to attract 650,000 affluent customers in less than seven years. These customers called 24 hours a day, seven days a week to pay bills, trade stock, arrange mortgages or buy any of 25 financial services.1

The concept of a bank with no branches originated in the convergence of improvements in call center technology, the availability of an automatic teller machine network to provide cash, and a high level of dissatisfaction with the service in the established banks. Meanwhile, research by First Direct revealed a substantial segment of bank customers who didn’t want to visit their branches or found the hours inconvenient.

Traditional banks ignored phone banking at first. However, the explosive growth of First Direct soon caught their attention. Within five years, there were 14 direct competitors with another 15 rivals using different technologies such as touch tone–based services. How did First Direct keep up with rapid growth and beat so many well-funded imitators? One answer is that they had very low operating costs, which meant low customer charges, while their highly trained banking representatives delivered the best customer satisfaction ratings in the industry.

First Direct’s most observable advantage was a prototypically market-driven organization. Their culture contrasted sharply with the formality of the established banks and emphasized openness, being right the first time and responsiveness. The 2,400 banking representatives saw themselves as problem solvers providing trouble-free banking with a personal touch. They were supported with extensive investments in information technology and training. These systems also enabled the firm to learn a great deal about their customers and cross-sell other products. Yet there was no complacency within the management team. They realized they would have to do more to tighten relations with customers while providing Internet-based banking services to stay ahead in the future. By working hard to build a market-driven organization, First Direct has stayed on top in the intensely competitive U.K. market for telephone banking.

Failing to Monitor Vital Signs

In contrast, Johnson & Johnson’s cardiology unit squandered its lead in a new market by failing to react to market changes. Like First Direct, J&J was a pioneer in defining a new market in 1994 when it introduced a revolutionary device called a stent, which held open obstructed heart vessels with a tiny metal scaffold. The benefits of this new device were so compelling that cardiologists adopted it en masse. Within two years, J&J had sold a billion dollars worth—at 80 percent gross margins—and held 91 percent of the market. Yet, by 1999, their share had collapsed to 8 percent and they faced two entrenched competitors.2

How did this highly regarded marketer of Tylenol and Band-Aids lose what they thought was an insurmountable lead? At the head of a long list of shortcomings was a failure to listen to the market and keep innovating. Perhaps because they were new to the cardiology marketplace, they weren’t sensitive to the needs and frustrations of the doctors. The first version of their stent had limitations that doctors soon found annoying: it was hard to use in some situations, came in only one size and couldn’t easily be seen in the X-rays that were used to locate and then guide the stent through the arteries.

J&J was slow to address these problems because the small unit had its hands full just meeting demands. Also their ability to innovate was impeded by a culture with a pharmaceutical company mind-set that was unused to the speedy development cycles of medical devices firms, and a traditional organization with strong functional departments that created obstacles to a customer focus. Their challengers had an advantage because they were configured into teams that were adept at getting products to market quickly. When J&J finally made improvements, their rivals had already beaten them to market with products that were easier to use and less expensive.

These rivals also benefited from J&J’s inflexibility in pricing as hospitals struggled to cope with the unexpectedly high cost of stents. Initially insurers wouldn’t pay these costs, but they relented in the face of compelling evidence of the lifesaving and cost benefits. While the stent ultimately won the support of insurers, J&J’s higher-priced products didn’t. The company’s lack of empathy for the cost pressures of the hospitals alienated influential luminaries in the field who instead welcomed the new competition.

UNDERSTANDING THE ORIENTATION TO THE MARKET

How did First Direct stay on the top of its market while Johnson & Johnson lost control of the market it helped to create? Both firms launched breakthrough innovations, but the difference was that First Direct was more market-driven. It demonstrated a superior ability to understand, attract and keep valuable customers. This is the definition of a market-driven firm.

By putting “superior” into this definition we remind ourselves that winning in a competitive market means outperforming competitors. Our abilities cannot be judged without reference to the “best of class” competitor or competitive alternative. I am frequently asked who are the most market-oriented firms. This is not the right question, because there are no absolute standards. What matters is being closer to your market than your rivals.

The definition also incorporates Drucker’s dictum3 that the purpose of a business is to attract and satisfy customers at a profit. But satisfaction is not sufficient, for customer acquisition is costly, so real profitability comes from keeping valuable customers by building deep loyalty that is rooted in mutual trust, bilateral commitments and intense communication.

Market-driven organizations know their markets so thoroughly that they are able to identify and nurture their valuable customers, and have no qualms about discouraging the customers that drain profits—those that are fickle and cost a lot to serve. Thus, being market-driven is about having the discipline to make sound strategic choices and implement them consistently and thoroughly. It is not about being all things to all people.

Three Elements of Successful Market Driven Organizations

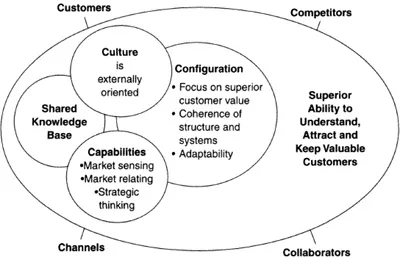

How do market-driven organizations achieve their superior ability to understand, attract and keep valuable customers and consistently win in their markets? What is it that sets apart exemplars like the brokerage house Edward Jones, upscale retailer Nordstrom, discounter Wal-Mart, or supercompetitive MCI and Dell Computer from their rivals? Why was Nike able to prevail over Adidas and Reebok for so long and why are these rivals starting to close the gap? A decade’s worth of research and the careful dissection of best practices has banished the myth of a simple answer. Reality is found in the artful combination of the defining elements shown in Figure 1–1.

• An externally oriented culture with the dominant beliefs, values and behaviors emphasizing superior customer value and the continual quest for new sources of advantage.

FIGURE 1–1

The Elements of a Market Orientation

• Distinctive capabilities in market sensing, market relating, and anticipatory strategic thinking. This means market-driven firms are better educated about their markets and better able to form close relationships with valued customers. The clarity of their strategic thinking helps them devise winning strategies that anticipate rather than react to market threats and opportunities.

• A configuration that enables the entire organization continually to anticipate and respond to changing customer requirements and market conditions. This includes all the other capabilities for delivering customer value—from product design to order fulfillment, plus an adaptive organization design and all the supporting systems, controls, measures and human resource policies. All these aspects of the configuration are aligned with a superior value proposition.

Supporting these three elements is a shared knowledge base in which the organization collects and disseminates its market insights. This knowledge builds relationships with customers, informs the company’s strategy and increases the focus of employees on the needs of the market. Advances in information technology present new opportunities to build this shared knowledge base, but only if the technology is applied with a clear market focus.

These elements reinforce one another in a market-driven organization. They don’t simply add together; instead they are multiplicative, so a weakness in one area afflicts the others. A rigidly functional organization with fiefdoms that carefully protect their turf will thwart the sharing of market learning and undermine efforts to introduce an open, participative culture. Each of these elements must be at least as good as the best of the rivals if the overall market orientation is to ensure the strategy gains an advantage.

The Role of Culture

A market-driven culture is much more than a market mantra. We are all familiar with the sort of market-orientation slogans to which most firms nowadays pay lip service:

The customer is at the top of the organization chart (Scandinavian Airline Systems).

Our mission is to find needs and fill them, not make products and sell them (Colgate).

Do business the way the customer wants to do business (US West).

If we’re not customer-driven our cars won’t be either (Senior Officer, Ford Motor Co.).

Customer satisfaction is the basis of our legitimacy (Tektronix).

Although slogans may be useful as reminders on wallet cards or rallying points in speeches, they seldom pervade or motivate an organization. Some reflect an underlying organization that is tightly aligned to its present and prospective markets, but others are mere facades that mask an internally focused culture but do not truly change it. Because they give the appearance that something is being done, they can actually be obstacles to real cultural change. The true test is not in what the organization says about itself but whether it acts in a way that reflects a culture aligned to the market.

In a market-driven firm, a pervasive market orientation is woven into the fabric of the organization. It is seen in what Jan Carlson, then CEO of the Scandinavian Airlines System, called the “million moments of truth” that determine the collective experience of customers as they interact with cabin staff, ticket agents, baggage handlers, and ticket takers. Whether these front-line people actually deliver superior customer value depends on their having the right incentives, tools and organizational setting. When they are part of a culture that insists on putting the customer first, while staying ahead of competitors, they have a reason for doing their jobs. Then “quality” becomes a collective dedication rather than an imposed dictum, “customer retention” a meaningful motivation rather than a mechanical metric, and “cross-functional teams” are mechanisms for improvement rather than a time-consuming indulgence.

On the other hand, a lack of a market-driven culture was one of the factors that contributed to Motorola’s downfall in the cellular telephone market. Its failure to develop digital systems and address customer service problems led to the decline of its share of the cellular phone from 60 percent to 34 percent between 1994 and 1998. Motorola was focused on making a better analog phone while the market was marching toward digital technology. It mishandled relationships with key customers operating cellular networks and underestimated the challenge from rivals such as Nokia, Qualcomm, and Lucent.4

The signals from its main customers couldn’t have been clearer. In the early 1990s executives from McCaw Cellular (now AT&T Wireless Services) decided the future of cellular was digital. Over the next few years, they met repeatedly with Motorola managers who said they would work on it. Yet in 1996, just as AT&T was rolling out its digital network, Motorola unveiled its Star TAC phone—a design marvel, light, smaller than a cigarette pack, and analog! AT&T had no choice but to turn to Nokia and Ericsson for digital handsets. Why did Motorola miss or ignore the signals from its customers and rivals? Some argue it was hubris; that the company was blinded by its success in creating the cellular phone market. However, Christopher Galvin, the CEO, also attributed the problems to a culture that was engineering and product-driven and distracted by internal rivalries.

Contrast Motorola’s aloofness with the behavior of John Chambers, the CEO of Cisco Systems, the networking giant that provides the routers, hubs and switches that make the Internet feasible. He is passionate about avoiding the arrogance that makes technology-driven companies unresponsive to their customers. Before his first board meeting as chief executive, he insisted on staying to sort out a customer problem and was half an hour late for the meeting. It was a clear sign that customers were a top priority. Every evening he goes through voice mail from managers who are dealing with customers on the “critical list.” He insists on voice mail because he wants to hear the emotion in the voices, which is undoubtedly amplified because these managers’ pay is closely tied to customer satisfaction levels. These signals from the top contribute greatly to the distinctive “feel” of Cisco that sets the company apart.

Markets eventually punish firms with arrogant and unresponsive cultures. When this happens, the shock to the system is so great that the dysfunctional values and beliefs can finally be challenged and displaced. Motorola was forced to attack its problems by consolidating its feuding fiefdoms under a common umbrella and then making a concerted effort to patch up relations with customers. One customer reported, “We are finally seeing Motorola acting like a hungry vendor who needs our business rather than an arrogant vendor entitled to our business.”

The Role of Capabilities

In addition to culture, a market-driven organization has superior capabilities in market sensing—reading and understanding the market. It also excels in market relating—creating and maintaining relationships with customers. Finally, the market-driven organization has capabilities in strategic thinking that allow it to align its strategy to the market and help it anticipate market changes.

Intuit offers a powerful demonstration of how these superior capabilities contribute to a company’s success. How did Intuit’s Quicken gain a near monopoly in personal finance software despite fierce competition from Microsoft and others? When Intuit launched Quicken in 1983, it faced 43 competing products and soon found itself staring down Microsoft, which had bested rivals in word processing, spreadsheets and presentations.

Yet Intuit managed not only to survive but to dominate. By 1998, Quicken held 75 percent of the market because it was easier to use than the alternatives. The vast majority of Quicken customers simply buy the program, load it into their computer, and begin using it without reading the manual. This delights customers who then tell their friends. It also pleases the makers of the progra...