![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

1

Brand Leadership—The New Imperative

It’s a new brand world.

—Tom Peters

A brand strategy must follow the business strategy.

—Dennis Carter, Intel

BRAND MANAGEMENT—THE CLASSIC MODEL

In May 1931, Neil McElroy, who later rose to be a successful CEO of Procter & Gamble (P&G) and still later became the U.S. secretary of defense, was a junior marketing manager responsible for the advertising for Camay soap. Ivory (“99.44% pure” since 1879) was then the king at P&G, while the company’s other brands were treated in an ad hoc manner. McElroy observed that the Camay marketing effort was diffuse and uncoordinated (see the 1930 Camay ad in Figure 1-1), with no budget commitment or management focus. As a result, Camay drifted and languished. Frustrated, McElroy wrote a now-classic memo proposing a brand-focused management system.

The McElroy memo (excerpted in Figure 1-2) detailed the solution—a brand management team that would be responsible for creating a brand’s marketing program and coordinating it with sales and

FIGURE 1-1

Camay ad, June 1930

manufacturing. This memo, which built on the ideas and activities of several people inside and outside P&G, has had a profound effect on how firms around the world manage their brands.

The system McElroy proposed was geared to solve “sales problems” by analyzing sales and profits for each market area in order to

FIGURE 1-2

EXCERPT FROM THE 1931 NEIL McELROY P&G “BRAND MANAGEMENT” MEMO

This May 1931 memo, written in part to defend the hiring of two new people, describes a brand management team consisting of a “brand man,” an “assistant brand man,” and several “field check-up” employees, The following excerpt describes the duties and responsibilities of the “brand man” (with occasional clarifications added in brackets).

BRAND MAN

(1) Study carefully shipments of his brands by units.

(2) Where brand development is heavy and where it is progressing, examine carefully the combination of effort that seems to be clicking and try to apply this same treatment to other territories that are comparable.

(3) Where brand development is light

(a) Study the past advertising and promotional history of the brand; study the territory personally at first hand—both dealers and consumers—in order to find out the trouble.

(b) After uncovering our weakness, develop a plan that can be applied to this local sore spot. It is necessary, of course, not simply to work out the plan but also to be sure that the amount of money proposed can be expected to produce results at a reasonable cost per case.

(c) Outline this plan in detail to the Division Manager under whose jurisdiction the weak territory is, obtain his authority and support for the corrective action.

(d) Prepare sales helps and all other necessary material for carrying out the plan. Pass it on to the districts. Work with the salesmen while they are getting started. Follow through to the very finish to be sure that there is no let-down in sales operation of the plan.

(e) Keep whatever records are necessary, and make whatever field studies are necessary to determine whether the plan has produced the expected results.

(4) Take full responsibility, not simply for criticizing individual pieces of printed word copy, but also for the general printed word plans for his brands.

(5) Take fall responsibility for all other advertising expenditures on his brands [such as in-store displays and promotions].

(6) Experiment with and recommend wrapper [packaging] revisions.

(7) See each District Manager a number of times a year to discuss with him any possible faults in our promotion plans for that territory.

identify problem markets. The brand manager conducted research to understand the causes of the problem, developed response programs to turn it around, and then used a planning system to help ensure that the programs were implemented on time. The responses used not only advertising but also other marketing tools, such as pricing, promotions, in-store displays, salesforce incentives, and packaging changes or product refinements.

In part, the classic brand management system was successful at P&G and elsewhere because it was typically staffed by exceptional planners, doers, and motivators. The process of managing a complex system—often involving R&D, manufacturing, and logistics in addition to advertising, promotion, and distribution-channel issues-required management skills and a get-it-done ethic. Successful brand managers also needed to have exceptional coordination and motivational skills because the brand manager typically had no direct line authority over the people (both inside and outside the company) involved in implementing branding programs.

Although it was not specifically discussed in his memo, the premise that each brand would vigorously compete with the firm’s other brands (both for market share and within the company for resources) was an important aspect of McElroy’s conceptualization of brand management. Contemporary accounts of McElroy’s thoughts suggest the source for this idea was General Motors, which had distinct brands like Chevrolet, Buick, and Oldsmobile competing against one another. The brand manager’s goal was to see the brand win, even if winning came at the expense of other brands within the firm.

The classic brand management system usually limited its scope to a relevant market in a single country. When a brand was multinational, the brand management system usually was replicated in each country, with local managers in charge.

Finally, in the original P&G model, the brand manager tended to be tactical and reactive, observing competitor and channel activity as well as sales and margin trends. When problems were detected, the goal of the response programs was to “move the needle” as soon as possible, with the process largely driven by sales and margins. Strategy was often delegated to an agency or simply ignored.

BRAND LEADERSHIP—THE NEW IMPERATIVE

The classic brand management system has worked well for many decades for P&G and a host of imitators. It manages the brand and makes things happen by harnessing the work of many. However, it can fall short in dealing with emerging market complexities, competitive pressures, channel dynamics, global forces, and business environments with multiple brands, aggressive brand extensions, and complex subbrand structures.

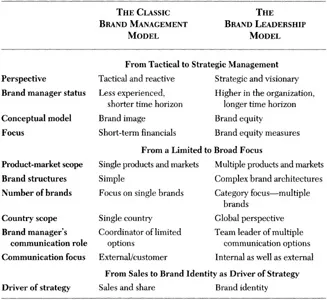

As a result, a new model is gradually replacing the classic brand management system at P&G and many other firms. The emerging paradigm, which we term the brand ledership model, is very different. As Figure 1-3 summarizes, it emphasizes strategy as well as tactics, its scope is broader, and it is driven by brand identity as well as sales.

FROM TACTICAL TO STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT

The manager in the brand leadership model is strategic and visionary rather than tactical and reactive. He or she takes control of the brand strategically, setting forth what it should stand for in the eyes of the customer and relevant others and communicating that identity consistently, efficiently, and effectively.

To fill this role, the brand manager must be involved in creating the business strategy as well as implementing it. The brand strategy should be influenced by the business strategy and should reflect the same strategic vision and corporate culture. In addition, the brand identity should not promise what the strategy cannot or will not

FIGURE 1-3

Brand Leadership—The Evolving Paradigm

deliver. There is nothing more wasteful and damaging than developing a brand identity or vision based on a strategic imperative that will not get funded. An empty brand promise is worse than no promise at all.

Higher in the organization

In the classic brand management system, the brand manager was too often a relatively inexperienced person who rarely stayed in the job more than two to three years. The strategic perspective calls for the brand manager to be higher in the organization, with a longer-term job horizon; in the brand leadership model, he or she is often the top marketing professional in the organization. For organizations where there is marketing talent at the top, the brand manager can be and often is the CEO.

Focus on brand equity as the conceptual model

The emerging model can be captured in part by juxtaposing brand image and brand equity. Brand image is tactical—an element that drives short-term results and can be comfortably left to advertising and promotion specialists. Brand equity, in contrast, is strategic—an asset that can be the basis of competitive advantage and long-term profitability and thus needs to be monitored closely by the top management of an organization. The goal of brand leadership is to build brand equities rather than simply manage brand images.

Brand equity measures

The brand leadership model encourages the development of brand equity measures to supplement short-term sales and profit figures. These measures, commonly tracked over time, should reflect major brand equity dimensions such as awareness, loyalty, perceived quality, and associations. Identifying brand identity elements that differentiate and drive customer-brand relationships is a first step toward creating a set of brand equity measures.

FROM A LIMITED TO A BROAD FOCUS

In the classic P&G model, the scope of the brand manager was limited to not only a single brand but also one product and one market. In addition, the communication effort tended to be more focused (with fewer options available), and internal brand communication was usually ignored. In the brand leadership model, the challenges and contexts are very different, and the task has been expanded.

Multiple products and markets

In the brand leadership model, because a brand can cover multiple products and markets, determining the brand’s product and market scope becomes a key management issue.

Product scope involves the management of brand extensions and licensing programs. To which products should the brand be attached? Which products exceed the brand’s current and target domains? Some brands, such as Sony, gain visibility and energy from being extended widely; customers know there will always be something new and exciting under the Sony brand. Other brands are very protective of a strong set of associations. Kingsford Charcoal, for instance, has stuck to charcoal and products directly related to charcoal cooking.

Market scope refers to the stretch of the brand across markets. This stretch can be horizontal (as with 3M in the consumer and industrial markets) or vertical (3M participating in both value and premium markets). Some brands, such as IBM, Coke, and Pringles, use the same identity across a broad set of markets. Other situations, though, require multiple brand identities or multiple brands. For example, the GE brand needs different associations in the context of jet engines than it does in the context of appliances.

The challenge in managing a brand’s product and market scope is to allow enough flexibility to succeed in diverse product markets while still capturing cross-market and cross-product synergies. A rigid, lockstep brand strategy across product markets risks handicapping a brand facing vigorous, less-fettered competitors. On the other hand, brand anarchy will create inefficient and ineffective marketing efforts. A variety of approaches, detailed in Chapters 2 and 4, can address these challenges.

Complex brand architectures

Whereas the classic brand manager rarely dealt with extensions and subbrands, a brand leadership manager requires the flexibility of complex brand architectures. The need to stretch brands and fully leverage their strength has led to the introduction of endorsed brands (such as Post-its by 3M, Hamburger Helper by Betty Crocker, and Courtyard by Marriott) and subbrands (such as Campbell’s Chunky, Wells Fargo Express, and Hewlett-Packard’s LaserJet) to represent different product markets, and sometimes an organizational brand as well. Chapters 4 and 5 examine brand architecture structures, concepts, and tools.

Category focus

The classic P&G brand management system encouraged the existence of competing brands within categories—such as Pantene, Head & Shoulders, Pert, and Vidal Sassoon in hair care—because different market segments were covered and competition within the organization was thought to be healthy. Two forces, however, have convinced many firms to consider managing product categories (that is, groupings of brands) instead of a portfolio of individual brands.

First, because retailers of consumer products have harnessed information technology and databases to manage categories as their unit of analysis, they expect their suppliers to also bring a category perspective to the table. In fact, some multicontinent retailers are demanding one single, worldwide contact person for a category, believing that a country representative cannot see enough of the big picture to help the retailer capture the synergies across countries.

Second, in the face of an increasingly cluttered market, sister brands within a category find it difficult to remain distinct, with market confusion, cannibalization, and inefficient communication as the all-too-common results. Witness the confused positioning overlap that now exists in the General Motors family of brands. When categories of brands are managed, clarity and efficiency are easier to attain. In addition, important resource-allocation decisions involving communication budgets and product innovations can be made more dispassionately and strategically, because the profit-generating brand no longer automatically controls the resources.

Under the new model, the brand manager’s focus expands from a single brand to a product category. The goal is to make the brands within a category or business unit work together to provide the most collective impact and the strongest synergies. Thus, printer brands at HP, cereal brands at General Mills, or hair care brands at P&G need to be managed as a team to maximize operational efficiency and marketing effectiveness.

Category or bus...