- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

David Levy brings these "ghostly apparitions" to life. With fascinating scenarios both real and imagined, he shows how comets have wreaked their special havoc on Earth and other planets. Beginning with ground zero as comets take form, we track the paths their icy, rocky masses take around our universe and investigate the enormous potential that future comets have to directly affect the way we live on this planet and what we might find as we travel to other planets. In this extraordinary volume, David Levy shines his expert light on a subject that has long captivated our imaginations and fears, and demonstrates the need for our continued and rapt attention.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

FROM DUST TO DUST

—I am like a slip of comet,

Scarce worth discovery, in some corner seen

Bridging the slender difference of two stars,

Come out of space, or suddenly engender’d

By heady elements, for no man knows:

But when she sights the sun she grows and sizes

And spins her skirts out, while her central star

Shakes its cocooning mists; and so she comes

To fields of light; millions of travelling rays

Pierce her; she hangs upon the flame-cased sun,

And sucks the light as full as Gideon’s fleece:

But then her tether calls her; she falls off,

And as she dwindles shreds her smock of gold

Amidst the sistering planets, till she comes

To single Saturn, last and solitary;

And then goes out into the cavernous dark.

So I go out: my little sweet is done:

I have drawn heat from this contagious sun:

To not ungentle death now forth I run.

Scarce worth discovery, in some corner seen

Bridging the slender difference of two stars,

Come out of space, or suddenly engender’d

By heady elements, for no man knows:

But when she sights the sun she grows and sizes

And spins her skirts out, while her central star

Shakes its cocooning mists; and so she comes

To fields of light; millions of travelling rays

Pierce her; she hangs upon the flame-cased sun,

And sucks the light as full as Gideon’s fleece:

But then her tether calls her; she falls off,

And as she dwindles shreds her smock of gold

Amidst the sistering planets, till she comes

To single Saturn, last and solitary;

And then goes out into the cavernous dark.

So I go out: my little sweet is done:

I have drawn heat from this contagious sun:

To not ungentle death now forth I run.

—GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS, ENGLISH POET AND JESUIT PRIEST, AFTER OBSERVING TEMPEL’S COMET IN 18641

I MAGINE A PACKAGE OF rock and ice, a small world lost in the depths of space far beyond Pluto. No larger than a village, this world, which we call a comet, moves lazily around the Sun, which is so far away that it appears only as a bright star in its black sky. Suddenly, something—maybe a passing star—causes it to shift. Instead of moving around the Sun, the ball of rock and ice now moves in a new orbit that takes it closer to the solar system’s central star. Over hundreds of thousands of years, the Sun brightens as the comet gets closer, passing Pluto and Neptune as it works its way inward. Jupiter’s mighty clouds and storms beckon, but it ignores them in its relentless push toward warmth and the Sun.

Not long after it passes Jupiter, the Sun’s rays start their slow work on the body’s ices. One by one, they heat and turn directly into gases. After a period of quiet lasting the comet’s entire lifetime of 4.5 billion years, the comet awakens, throws off its covers, and, like a peacock, spreads its material into space. Now surrounded by a cloud of gases and dust we call a coma, it forges ahead toward Mars, Earth, and Sun.

A BRAVE NEW WORLD

On Earth, it is May 20, 1990, and after giving a lecture about comet hunting to a group of visitors, I head home to my backyard observatory. Although the darkness of the predawn sky is lessened by a last quarter moon, I decide to begin searching for comets. Turning off white lights andswitching on red ones, so that my eyes will adapt to the darkness outside, I walk into the yard. There I have a garden shed that I had made into an observatory some years earlier.

Tucson’s two-hundred-year-old San Xavier mission must have seen several magnificent comets. Painting by James V. Scotti.

Out in the garden shed observatory that morning, I grab a handle and give a shove. Slowly, the big roof starts moving, and a minute later, the observatory is open to the sky and I begin a slow search through the eastern sky sweep with Miranda, my sixteen-inch-diameter reflecting telescope named after the Shakespearean character who spoke of a “brave new world.” Swinging the telescope north to keep as far from the Moon as possible, I “sweep” through the constellation of Andromeda, past the bright star Alpheratz, and on into the four-cornered figure of Pegasus, the winged horse.

Not far from that bright star, my telescope stops as a soft, fuzzy patch of light enters the field of view. I check several atlases of the sky, but none suggests that any fuzzy spot belongs in that lonely area. By now it is dawn, and my observing has ended. Twenty-four hours later, I look again. The “spot” is in a different position—it has moved! I have found a new comet—the holy grail of an observer. Now certain that the comet is a new one, I report it to the International Astronomical Union, which maintains a clearinghouse for discoveries called the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. After more than 4 billion years of anonymity, the new world is finally announced.

By early July of 1990, the new comet is experiencing the full warmth of the Sun. As it crosses the summer Milky Way, it grows a graceful tail as its ionized gas and dust particles escape.

GHOSTLY APPARITIONS

Comets first came to me one bright afternoon in the late 195Os. Just as our Hebrew school class was about to start, I lazily looked out the window and saw what seemed to be a comet hanging in the western sky, its bright tail calling our attention. The other children teased me as I wondered aloud how we would report this wondrous apparition. It couldn’t have been a comet, though: the two major comets during the 1950s both appeared in 1957, and neither was bright enough to be seen clearly in daylight. My childhood comet was probably the vapor trail of an airplane, or a high cloud.

Had I brought the sighting to the attention of my Hebrew teacher, he might have told us of a passage from the first book of Chronicles. It describes what could be a comet that appeared over Jerusalem during the time of King David. The biblical passage is read every year at the Passover seder:

And David lifted up his eyes, and saw the angel of the Lord standing between the earth and the heaven, having a drawn sword in his hand stretched out over Jerusalem. 2

Could a sword in the sky be a comet? We do know that the ancient Hebrews, like their Arabic neighbors, enjoyed looking at the night sky and sought meaning among its many stars and events. A bright comet appearing once every two decades or so, would have attracted their attention as much then as now.

Despite the fact that I had never seen a comet, when I had to choose a topic for a sixth-grade public-speaking exercise in 1960, I chose comets. It was the first time I had ever given a speech in front of a group of people, and I was uneasy. I committed to memory every fact about comets that I could lay my hands on, but on speech day I was so nervous that I held a blank sheet of paper in front of me so I wouldn’t have to look at my classmates.

The speech was a three-minute summary of what we understood about comets in 1960. Comets, I said, are large “dirty snowballs,” balls of ices and dust, and they travel around the Sun in wide, looping paths, or orbits. The most famous, I said, was Halley’s comet, which loops around the Sun every seventy-six years. Traveling all the way to a place beyond Neptune, the lonely comet then heads toward the Sun. Back in 1960, Halley’s next visit in 1986 seemed a very long time in the future. I might have added that comets get discovered by people who, with small telescopes and perseverance, seek for them in the night sky.

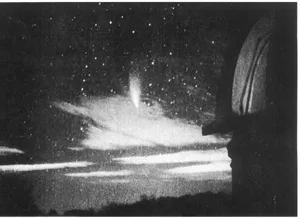

Comet Hale-Bopp, photographed by Jean Mueller on March 5, 1997. The observatory dome houses Palomar’s forty-eight-inch-diameter Oschin Schmidt telescope.

The speech was pretty well received by my classmates. Sitting in the back, our teacher commented, “Nice speech, Levy. Can I see your notes?” Embarrassed, I looked down at the blank sheet of paper and the class broke out in laughter.

DIRTY SNOWBALLS IN THE NIGHT

Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, our understanding of comets had undergone a major change in the few years preceding my speech. Before 1950, comets were thought of as giant clumps of sand. That was the year that Fred Lawrence Whipple, an astronomer at Harvard, completed a study that seemed at first to be rather arcane. It concerned the little dust particles left in the wake of comets. We see those particles every night of the year; when they fall into our atmosphere, they heat the surrounding air until it glows. The result is a meteor.

For more than a century, astronomers have known that these meteor streams are the debris of comets. The dust particles are expelled from the comet as it rounds the Sun, and then travel independently around the Sun. Because they collide with each other, these particles do not stay in their cometary orbits for very long. Within a million years, most of them would spiral into the Sun.

The problem, Whipple perceived, is if comets were simply flying sandbanks, they would not be able to replenish the supply of meteors that had vanished as they fell into the Sun. Whipple proposed that a comet is a vast storehouse of ices, several miles in diameter, mixed with dust. When the comet is far from the Sun, the comet is inert. But as it nears the Sun and warms, the ices sublimate, or turn into gases, which leave the comet with explosive force. When this happens, particles of dust by the millions spread out into space.3

WHERE DO COMETS COME FROM?

For almost all of its life, a comet roams through the blackness of space far from Earth and Sun. One of the darkest masses of material possible, the black snowball is all but invisible. The solar system contains two major storehouses of comets. Both were proposed independently around the same time that Whipple was defining the structure and composition of comets. One lies in a belt beyond the orbit of Neptune. It includes the planet Pluto, and several observed comets of large size, more than one hundred miles across. The belt is named after Gerard Kuiper, a Dutch planetary scientist who spent most of his career at the University of Arizona in Tucson. The other repository, the ancestral home of Comet Levy, which I found in 1990, is an enormous sphere several trillion miles out. Called the Oort cloud, for Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, this sphere completely circumscribes the solar system.

The Oort cloud is the result of a long game of interplanetary pinball. The youthful solar system was filled with comets—in Earth’s primordial sky there must have been dozens of bright comets at a time. Some of the comets collided with the planets. Others made close passes by planets, using their gravity to swing off into new orbits that would eventually land them near other planets. As the largest planet, Jupiter was the clear winner in this game. A comet swinging by Jupiter would get a gravitational hurl that would send the comet either out of the solar system forever, or off into the growing Oort cloud. Within about 500 million years of the solar system’s birth, the pinball game was all but over, its supply of cometary materials exhausted. As we saw with the collision of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter in 1994, the process continues even today, but at a far more leisurely rate.

HOW FAST DO COMETS TRAVEL?

Most comets move much faster than the Earth’s velocity around the Sun, which is about eighteen miles per second. Halley’s comet makes a wide loop every seventy-six years. Its farthest point from the Sun is beyond Neptune. When it is that far out, it parades through space very slowly; an airplane could probably keep up with it. As the comet moves in, it picks up speed. By the time it passes the Earth, it is sprinting along at close to forty miles per second.

HOW FAR DO COMETS GO?

To answer this question, we need to understand that comets, like people, cluster in families that are defined by their orbits. The best known is the Jupiter family, which consists of comets that have been so influenced by Jupiter’s gravity that their orbits are related to that of the giant planet. In October 1990, Gene and Carolyn Shoemaker and I discovered an object that we thought was an asteroid. It looked like a faint star, and had no coma or tail. We observed it on several nights, reporting the positions to astronomer Brian Marsden in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When Marsden calculated an orbit for the asteroid he designated 1990 UL3, he was surprised to plot the object’s moving from the vicinity of the Earth almost to the orbit of Jupiter, and back again in a period of several years. Its orbit was typical of a Jupiter-family comet, not an asteroid. He asked us to check the object’s appearance. A careful look at the discovery films, taken through the eighteen-inch-diameter camera at Palomar Observatory in the mountains north of San Diego, still showed a starlike object. As a further check, astronomer Steve Larson and I pointed a much larger telescope—a sixty-one-inch-diameter reflector atop the Catalina Mountains north of Tucson—toward the object, then took a series of five-minute-long exposures. When we looked at the computerized results, near the bottom of the field dense with stars was our object—with a faint tail forty thousand miles long!

Comet Hale-Bopp, photographed on April 7,1997, using an F3.5135mm lens and equatorial tracking drive. Photo by Bob and Sue Liefeld.

The next day, the Central Bureau issued an announcement that asteroid 1990 UL3 was now Periodic Comet Shoemaker-Levy 2. The comet had given its identity away because its orbit was typical of a Jupiter-family comet. Comets in this family revolve about the Sun in periods averaging six or seven years. The fastest-orbiting comet is Encke, which races around in three and onethird years. Some Jupiter-family comets take much longer, heading out into the outer solar system. Halley’s comet, the best-known member of the Jupiter family, has a seventy-six-year orbit.

Tethered to the Sun over periods of thousands of years are comets like Hale-Bopp, and the Great Comet of 1811. These comets travel incredible distances beyond the planets. The Comet of 1811 was visible to the naked eye for ten months. By December, the comet had a tail that covered almost a quarter of the sky. The comet was even credited with the coincidentally ultrafine wines from that year. I believe that the Comet of 1811 helped to inspire John Keats to compare the thrill of discovering a new work of literature to that of finding a new world. If this is true, then that long-departed comet, traveling to the very edge of the solar system and back in thousands of years, also traveled far enough to bridge the gap between science and poetry:

Much have I traveled in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien. 4

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien. 4

WHAT ARE ASTEROIDS?

Also called minor planets, asteroids are small, rocky bodies that orbit the Sun. The vast majority of the more than ten thousand known asteroids orbit the Sun between Mars and Jupiter, and are probably the remains of a planet near Jupiter that could never form because of the interference from Jupiter’s gravity.

But not all asteroids orbit within the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. So many asteroids crowd the belt that there are inevitable collisions that send newly formed fragments on orbits that take them virtually anywhere. Some fifty thousand years ago, one of these asteroids, as big as a large room, slammed into an area now part of northern Arizona. This danger of asteroids and comets hitting Earth will be explored later in our story.

HOW DO ASTEROIDS DIFFER FROM COMETS?

From the point of view of an observer with a telescope, there is a simple way to tell the difference between an asteroid and a comet. Both types of worlds move among the starry background of the sky. As the Greek version of their name implies, asteroids look like starry points of light in a telescope. Comets, or long-haired...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Chapter One From Dust to Dust

- Chapter Two Four Billion Years Ago

- Chapter Three Comets and the Origin of Life

- Chapter Four Three Billion Years Ago

- Chapter Five Sixty Five Million Years Ago

- Chapter Six Comets are Double Edged Swords

- Chapter Seven Earth’s First Cold War

- Chapter Eight A Time for Comets

- Chapter Nine A Field of Dreams

- Chapter Ten Target Earth

- Chapter Eleven Three Little Worlds

- Chapter Twelve Probing for Life in our Galaxy

- Chapter Thirteen Yes Virginia Comets Do Hit Planets

- Chapter Fourteenprescription for Doomsday

- Chapter Fifteenan Epilogue

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Comets by David Levy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.