- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

George Washington: The Crossing

About this book

The #1 New York Times bestselling book for many weeks, Jack Levin presents a beautifully designed account of George Washington’s historic crossing of the Delaware River and the decisive Battle of Trenton, with a foreword by his son, #1 New York Times bestselling author and radio host Mark R. Levin.

With the warm-hearted patriotism and passion he brought to his beautiful volume Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address Illustrated, Jack E. Levin illuminates a profound turning point of the American Revolution: the decisive Battle of Trenton and its prelude—General George Washington leading his broken and ailing troops in a fleet of small wooden boats across the ice-encased Delaware River.

While one iconic nineteenth-century painting made the crossing a familiar image, the significance of the against-all-odds victory put into motion on Christmas night, 1776, cannot be told enough. Jack Levin brings to light several vital perspectives, and draws his text from General Washington’s letter to the Continental Congress to describe the amazing account of the unlikely defeat of the Hessian army at Trenton.

As a father, Jack Levin inspired his sons—including Mark Levin, and Douglas, and Robert—with his love for America. Around the family table, he would share the facts and events of the nation’s founding, spark lively debates, and pass along his extensive knowledge and his deep and abiding patriotism. Featuring Revolution-era artwork, portraiture, and maps, George Washington: The Crossing imparts the same vivid, intimate telling, that of a father to his sons—the kind of history lesson that lives in the heart forever.

With the warm-hearted patriotism and passion he brought to his beautiful volume Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address Illustrated, Jack E. Levin illuminates a profound turning point of the American Revolution: the decisive Battle of Trenton and its prelude—General George Washington leading his broken and ailing troops in a fleet of small wooden boats across the ice-encased Delaware River.

While one iconic nineteenth-century painting made the crossing a familiar image, the significance of the against-all-odds victory put into motion on Christmas night, 1776, cannot be told enough. Jack Levin brings to light several vital perspectives, and draws his text from General Washington’s letter to the Continental Congress to describe the amazing account of the unlikely defeat of the Hessian army at Trenton.

As a father, Jack Levin inspired his sons—including Mark Levin, and Douglas, and Robert—with his love for America. Around the family table, he would share the facts and events of the nation’s founding, spark lively debates, and pass along his extensive knowledge and his deep and abiding patriotism. Featuring Revolution-era artwork, portraiture, and maps, George Washington: The Crossing imparts the same vivid, intimate telling, that of a father to his sons—the kind of history lesson that lives in the heart forever.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access George Washington: The Crossing by Jack E. Levin,Mark R. Levin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

FOREWORD

During the second week of March 1776, General George Washington scored a major victory four months before the Declaration of Independence was signed. He forced the British to leave the city of Boston, where the spark of the Revolution had been struck.

Washington had the heavy cannons that Colonel Henry Knox and his men had valiantly brought from Fort Ticonderoga and placed into position on Dorchester Heights, a piece of hilly land projecting into Boston Harbor. He had fortified the two highest hills, Bunker and Breed’s hills, and bombarded Boston and Boston Harbor with deadly shellfire daily.

The constant American bombardment convinced General Lord William Howe, commander of the British army in Boston, that only an evacuation of the city would save his troops from a military disaster.

In the following days Howe loaded 9,000 soldiers and their supplies on nearly 100 ships and sailed away, apparently headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The remaining Boston residents wildly hailed the American victory, but Washington did not take part. Instead he stared out to sea, wondering about the real destination of Lord Howe and the Royal Navy.

General Washington could not believe Howe was really en route to Halifax. With all the troops, ships, and war material the British had at their command, a movement to Nova Scotia would be a foolish mistake. It seemed to him a more realistic possibility that Howe might risk an attempt to take New York City and its great seaport.

The loss of New York City would be a terrible setback for the Americans. To check such a potential British manuver, Washington rushed troops overland from Boston to New York City. He set his men digging entrenchments from the Battery to the northern tip of Manhattan Island.

Washington had guessed right. Late in June 1776 the missing British fleet appeared. Lord Howe had more than 100 ships loaded with thousands of British and Hessian troops for an attack on New York City.

And so our story begins. . . .

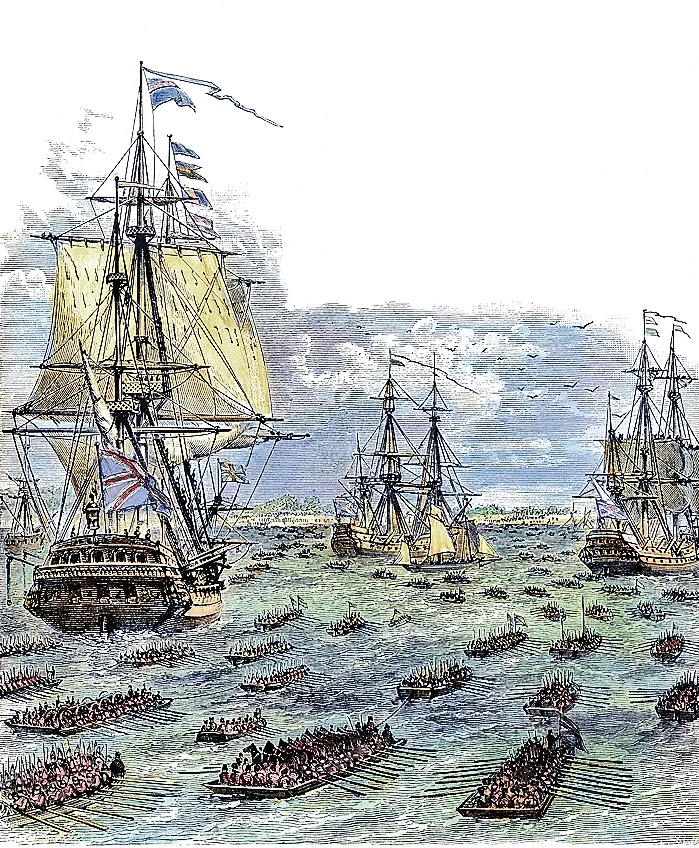

In August 1776, 20,000 British and Hessian battle-hardened veteran, fully equipped soldiers, under the command of General William Howe, were landed from Royal Navy warships at Gravesend, Long Island.

Royal Navy ships land Howe’s army of British and Hessian troops.

They attacked and smashed through the American Force stationed on Long Island by Washington to repel any attempt by the British to take New York City. Before the overwhelming English assault, the Colonial army was forced to fall back.

The Continental Army on Long Island retreats from the British and Hessian army’s overpowering attack.

General William Howe.

A valiant rearguard delaying action by Delaware and Maryland Continentals, commanded by General William Alexander, Lord Stirling, allowed the retreating Americans enough time to safely reach General Washington’s entrenchments at Brooklyn Heights.

General William Alexander, Lord Stirling. Lord Stirling leading his brave troops in battle against the British and Hessians at Long Island.

The British continued their assault on the Americans. With his back to open water and outnumbered, Washington was in danger of losing his whole army. He ordered his men to gather all the boats they could find and bring them to the East River at dusk. Colonel John Glover’s regiment of Massachusetts fishermen began the enormous task of transporting the American troops at night in a rainstorm to Manhattan Island. It was done so quietly the enemy never knew it was happening. The Americans got away with all their guns, horses, food, and ammunition. Washington took one of the last boats to cross as the foggy dawn lifted, and Howe and the Redcoats found Brooklyn empty.

British troops climb the Jersey Palisades to successfully attack and seize Fort Lee.

The British pressed their assault on the Americans, forcing General Washington to retreat from his positions in Manhattan, leaving Fort Washington, on the New York shore, and Fort Lee, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, to defend themselves against the entire British army and navy. The two forts fell to the Redcoats in quick succession with the loss of large quantities of valuable supplies and 2,600 American officers and men taken prisoners.

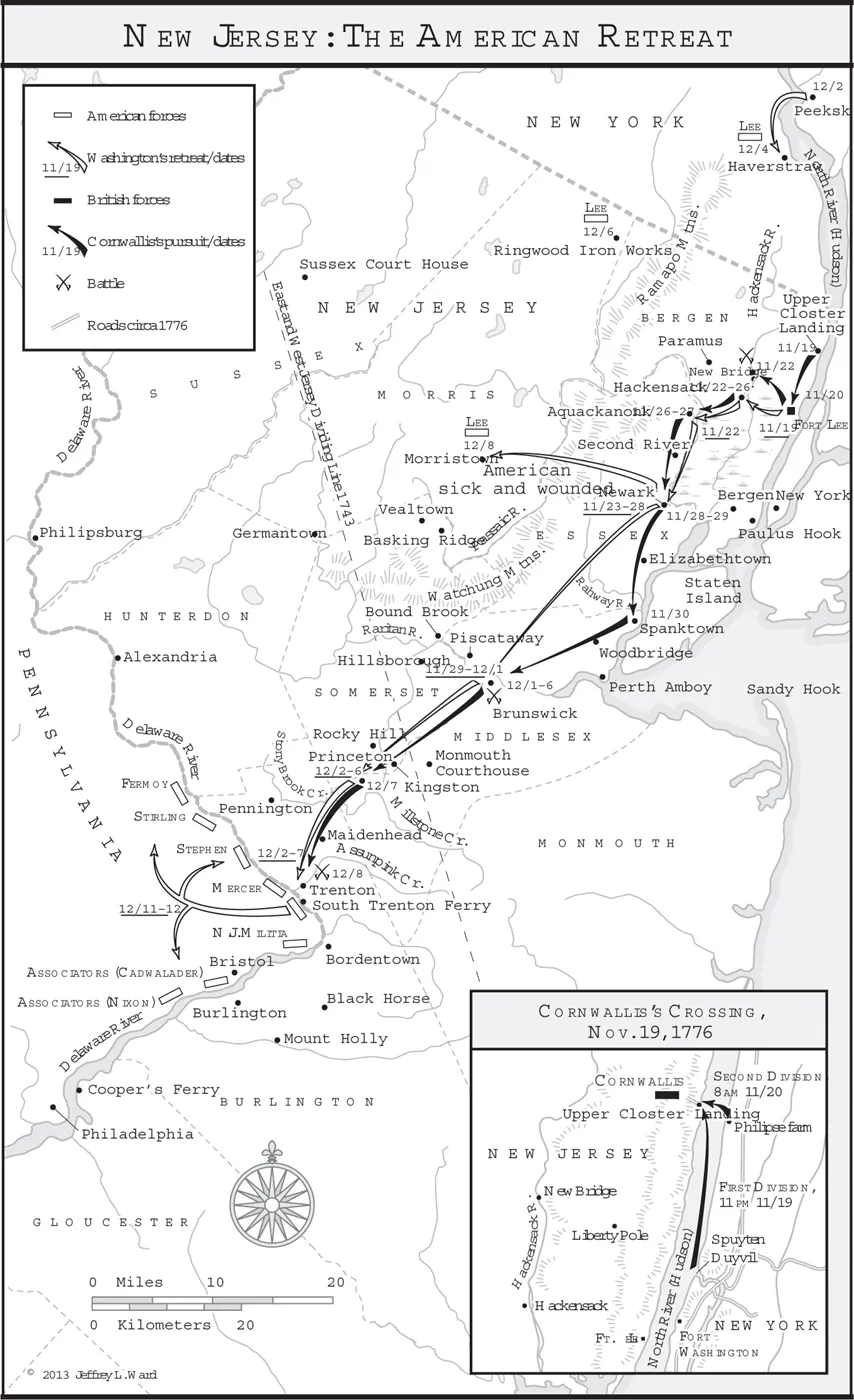

Map showing the area of General Washington’s retreat through Long Island, Manhattan, and New Jersey.

Having lost Long Island, Brooklyn, and Manhattan to the enemy, Washington realized General Howe’s next target would be the capital of the Revolution, the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His plan called for reaching Pennsylvania before the British.

On November 12, 1776, Washington led 3,000 men across the Hudson River into New Jersey. General Lord Cornwallis, commanding 10,000 British and Hessian troops, quickly followed, confident they’d catch and destroy the Americans in a short time. Pursuing the rebels relentlessly, they did not allow them to rest.

The weather turned cold and a steady chilling rain fell heavily. Weary, disheartened, sick, poorly equipped, with losses from death and desertion growing daily, Washington’s little army retreated westward across New Jersey. A pursuing British officer wrote, “Many of the Rebels who were killed were without shoes and stockings, and several were observed to have only linen drawers, also in great want of blankets, they must suffer extremely.” They did. But still they struggled onward.

General Washington and his army retreating across New Jersey.

Charles Cornwallis, British general, on November 25, 1776, set off across New Jersey with 10,000 men, determined to catch Washington, he said, as a hunter bags a fox.

Barely keeping his exhausted army ahead of the onrushing British, Washington reached the Delaware River on December 8, 1776. He ordered his troops to seize and destroy all the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Preface

- Epigraph

- Foreword

- The Crossing

- Author’s Note

- Photo Credits

- About Jack E. Levin and Mark R. Levin

- Copyright