![]()

“BUY THIS 24-YEAR-OLD AND GET ALL HIS FRIENDS ABSOLUTELY FREE”

We Are the Product

IF YOU’RE LIKE MOST PEOPLE, YOU THINK THAT ADVERTISING HAS NO INFLUENCE on you. This is what advertisers want you to believe. But, if that were true, why would companies spend over $200 billion a year on advertising? Why would they be willing to spend over $250,000 to produce an average television commercial and another $250,000 to air it? If they want to broadcast their commercial during the Super Bowl, they will gladly spend over a million dollars to produce it and over one and a half million to air it. After all, they might have the kind of success that Victoria’s Secret did during the 1999 Super Bowl. When they paraded bra-and-panty-clad models across TV screens for a mere thirty seconds, one million people turned away from the game to log on to the Website promoted in the ad. No influence?

Ad agency Arnold Communications of Boston kicked off an ad campaign for a financial services group during the 1999 Super Bowl that represented eleven months of planning and twelve thousand “man-hours” of work. Thirty hours of footage were edited into a thirty-second spot. An employee flew to Los Angeles with the ad in a lead-lined bag, like a diplomat carrying state secrets or a courier with crown jewels. Why? Because the Super Bowl is one of the few sure sources of big audiences—especially male audiences, the most precious commodity for advertisers. Indeed, the Super Bowl is more about advertising than football: The four hours it takes include only about twelve minutes of actually moving the ball.

Three of the four television programs that draw the largest audiences every year are football games. And these games have coattails: twelve prime-time shows that attracted bigger male audiences in 1999 than those in the same time slots the previous year were heavily pushed during football games. No wonder the networks can sell this prized Super Bowl audience to advertisers for almost any price they want. The Oscar ceremony, known as the Super Bowl for women, is able to command one million dollars for a thirty-second spot because it can deliver over 60 percent of the nation’s women to advertisers. Make no mistake: The primary purpose of the mass media is to sell audiences to advertisers. We are the product. Although people are much more sophisticated about advertising now than even a few years ago, most are still shocked to learn this.

Magazines, newspapers, and radio and television programs round us up, rather like cattle, and producers and publishers then sell us to advertisers, usually through ads placed in advertising and industry publications. “The people you want, we’ve got all wrapped up for you,” declares The Chicago Tribune in an ad placed in Advertising Age, the major publication of the advertising industry, which pictures several people, all neatly boxed according to income level.

Although we like to think of advertising as unimportant, it is in fact the most important aspect of the mass media. It is the point. Advertising supports more than 60 percent of magazine and newspaper production and almost 100 percent of the electronic media. Over $40 billion a year in ad revenue is generated for television and radio and over $30 billion for magazines and newspapers. As one ABC executive said, “The network is paying affiliates to carry network commercials, not programs. What we are is a distribution system for Procter & Gamble.” And the CEO of Westinghouse Electric, owner of CBS, said, “We’re here to serve advertisers. That’s our raison d’être.”

The media know that television and radio programs are simply fillers for the space between commercials. They know that the programs that succeed are the ones that deliver the highest number of people to the advertisers. But not just any people. Advertisers are interested in people aged eighteen to forty-nine who live in or near a city. Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, a program that was number one in its time slot and immensely popular with older, more rural viewers, was canceled in 1998 because it couldn’t command the higher advertising rates paid for younger, richer audiences. This is not new: the Daily Herald, a British newspaper with 47 million readers, double the combined readership of The Times, The Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Telegraph, folded in the 1960s because its readers were mostly elderly and working class and had little appeal to advertisers. The target audience that appeals to advertisers is becoming more narrow all the time. According to Dean Valentine, the head of United Paramount Network, most networks have abandoned the middle class and want “very chic shows that talk to affluent, urban, unmarried, huge-disposable-income 18-to-34-year-olds because the theory is, from advertisers, that the earlier you get them, the sooner you imprint the brand name.”

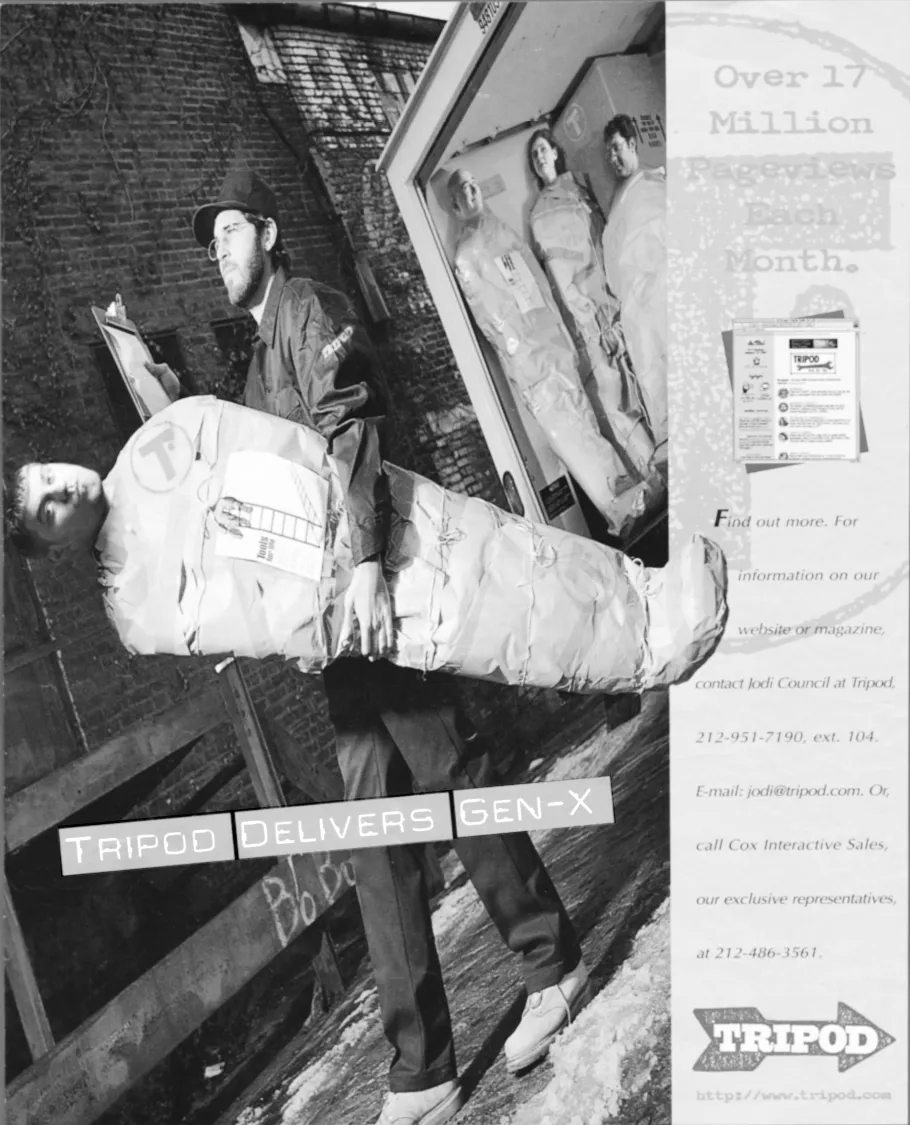

“Tripod Delivers Gen-X,” proclaims a sinister ad for a Website and magazine that features a delivery man carrying a corpselike consumer wrapped from neck to toe in brown paper. Several other such “deliveries” are propped up in the truck. “We’ve got your customers on our target,” says an ad for financial services that portrays the lower halves of two people embedded in a target. “When you’ve got them by the ears their hearts and minds will follow,” says an ad for an entertainment group. And an ad for the newspaper USA Today offers the consumer’s eye between a knife and a fork and says, “12 Million Served Daily.” The ad explains, “Nearly six million influential readers with both eyes ingesting your message. Every day.” There is no humanity, no individuality in this ad or others like it—people are simply products sold to advertisers, of value only as potential consumers.

Newspapers are more in the business of selling audiences than in the business of giving people news, especially as more and more newspapers are owned by fewer and fewer chains. They exist primarily to support local advertisers, such as car dealers, realtors, and department store owners. A full-page ad in The New York Times says, “A funny thing happens when people put down a newspaper. They start spending money.” The ad continues, “Nothing puts people in the mood to buy like newspaper. In fact, most people consider it almost a prerequisite to any spending spree.” It concludes, “Newspaper. It’s the best way to close a sale.” It is especially disconcerting to realize that our newspapers, even the illustrious New York Times, are hucksters at heart.

Once we begin to count, we see that magazines are essentially catalogs of goods, with less than half of their pages devoted to editorial content (and much of that in the service of the advertisers). An ad for a custom publishing company in Advertising Age promises “The next hot magazine could be the one we create exclusively for your product.” And, in fact, there are magazines for everyone from dirt-bike riders to knitters to mercenary soldiers, from Beer Connoisseur to Cigar Aficionado. There are plenty of magazines for the wealthy, such as Coastal Living “for people who live or vacation on the coast.” Barron’s advertises itself as a way to “reach faster cars, bigger houses and longer prenuptial agreements” and promises a readership with an average household net worth of over a million.

The Internet advertisers target the wealthy too, of course. “They give you Dick,” says an ad in Advertising Age for an Internet news network. “We give you Richard.” The ad continues, “That’s the Senior V.P. Richard who lives in L.A., drives a BMW and wants to buy a DVD player and a kayak.” Not surprisingly, there are no magazines or Internet sites or television programs for the poor or for people on welfare. They might not be able to afford the magazines or computers but, more important, they are of no use to advertisers.

This emphasis on the affluent surely has something to do with the invisibility of the poor in our society. Since advertisers have no interest in them, they are not reflected in the media. We know so much about the rich and famous that it becomes a problem for many who seek to emulate them, but we know very little about the lifestyles of the poor and desperate. It is difficult to feel compassion for people we don’t know.

Publications and programs that target minorities are also only interested in the affluent. “At $446 billion, African American buying power is more than the GNP of Switzerland,” says an ad in Advertising Age. Another, for a “Black-owned agency,” implies it can “get you inside the soul of the African American consumer.” “Are You Skirting a Major Market?” asks an ad for a local Florida television station picturing a Latina in a very short skirt. It concludes, “Channel 23. Because South Florida spends a lot of dinero!” An ad for Latina magazine says, “She’s Latina. She spends more.” And the Hispanic Network tells advertisers that “Hispanic families are more responsive to advertising. And ads in Spanish are 5 times more persuasive.”

This persuasiveness seems pernicious in an ad placed by an advertising agency in Advertising Age after the 1998 reelection of George W. Bush as governor of Texas. “If you have high ambitions, hire us. He did,” says the ad opposite a full-page picture of Bush. The ad continues, “If we can create advertising that persuades Hispanic Democrats to vote Republican, we can get them to buy your product.” Although most of us know that politicians are sold like beer or soap these days, it is chilling to see this bragged about in an ad.

Early in 1999 William Eisner, head of an advertising agency in Milwaukee, began a multimillion-dollar campaign designed to repackage Republican presidential candidate Steve Forbes just as he once repackaged Mrs. Paul’s fishsticks. “We’re trying to resuscitate brands all the time that lost their luster with consumers,” said Mr. Eisner. “We’re doing the same with Steve.” To make the candidate look presidential, some commercials were shot in black and white with backdrops resembling the Oval Office.

Ethnic minorities will soon account for 30 percent of all consumer purchases. No wonder they are increasingly important to advertisers. Nearly half of all Fortune 1000 companies have some kind of ethnic marketing campaign. Nonetheless, minorities are still underrepresented in advertising agencies. African-Americans, who are over 10 percent of the total workforce, are only 5 percent of the advertising industry. Minorities are underrepresented in ads as well—about 87 percent of people in mainstream magazine ads are white, about 3 percent are African-American (most likely appearing as athletes or musicians), and less than 1 percent are Hispanic or Asian. As the spending power of minorities increases, so does marketing segmentation. Mass marketing aimed at a universal audience doesn’t work so well in a multicultural society, but cable television, the Internet, custom publishing, and direct marketing lend themselves very well to this segmentation. The multiculturalism that we see in advertising is about money, of course, not about social justice.

The same is true for the increased visibility of gay men and lesbians in advertising. The gay media have provided the lucrative market of gay men to advertisers, such as IBM, Benetton, Johnson & Johnson, and United Airlines, for years. Hartford Financial Services Group launched a 1998 campaign aimed at gays that not only appeared in the gay media but crossed over to mainstream media. Ads picturing pairings of pink and blue cars promoted Hartf...