- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

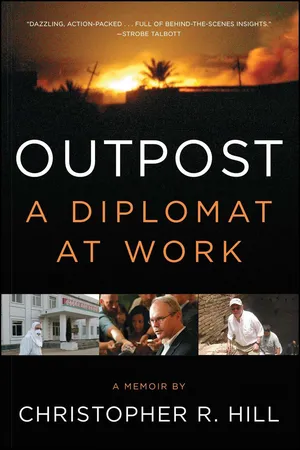

A “candid, behind-the-scenes” (The Dallas Morning News) memoir from one of our most distinguished ambassadors who—in his career of service to the country—was sent to some of the most dangerous outposts of American diplomacy.

Christopher Hill was on the front lines in the Balkans at the breakup of Yugoslavia. He participated in one-on-one meetings with the dictator Milosevic and traveled to Bosnia and Kosovo, and to the Dayton conference, where a truce was arrived at. He was the first American Ambassador to Macedonia; Ambassador to Poland, in the cold war; chief disarmament negotiator in North Korea; and Hillary Clinton’s hand-picked Ambassador to Iraq.

Outpost is Hill’s “lively, entertaining…introduction to the difficult game of diplomacy” (The Washington Post)—an adventure story of danger, loss of comrades, high stakes negotiations, and imperfect options. There are fascinating portraits of war criminals (Mladic, Karadzic), of presidents (Bush, Clinton, and Obama), of vice presidents including Dick Cheney, of Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, and of Ambassadors Richard Holbrooke and Lawrence Eagleburger, among others. Hill writes bluntly about the bureaucratic warfare in DC and expresses strong criticism of America’s aggressive interventions and wars of choice.

From the wars in the Balkans to the brutality of North Korea to the endless war in Iraq, Outpost “is a personal story, filled with the intricacies of living abroad, coping with the bureaucracy of the huge US foreign-policy establishment, and trying to persuade some very difficult people that America really does want to help them” (Providence Journal).

Christopher Hill was on the front lines in the Balkans at the breakup of Yugoslavia. He participated in one-on-one meetings with the dictator Milosevic and traveled to Bosnia and Kosovo, and to the Dayton conference, where a truce was arrived at. He was the first American Ambassador to Macedonia; Ambassador to Poland, in the cold war; chief disarmament negotiator in North Korea; and Hillary Clinton’s hand-picked Ambassador to Iraq.

Outpost is Hill’s “lively, entertaining…introduction to the difficult game of diplomacy” (The Washington Post)—an adventure story of danger, loss of comrades, high stakes negotiations, and imperfect options. There are fascinating portraits of war criminals (Mladic, Karadzic), of presidents (Bush, Clinton, and Obama), of vice presidents including Dick Cheney, of Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, and of Ambassadors Richard Holbrooke and Lawrence Eagleburger, among others. Hill writes bluntly about the bureaucratic warfare in DC and expresses strong criticism of America’s aggressive interventions and wars of choice.

From the wars in the Balkans to the brutality of North Korea to the endless war in Iraq, Outpost “is a personal story, filled with the intricacies of living abroad, coping with the bureaucracy of the huge US foreign-policy establishment, and trying to persuade some very difficult people that America really does want to help them” (Providence Journal).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

EARLY DIPLOMATIC LESSONS

There is a bleakness to Belgrade in the winter months, when snow instantly turns gray from the soot-filled air. So even on a clear day like that day in January 1961, everything seemed to have a dirty dampness to it.

The school bus that took me to and from the International School of Belgrade was a two-tone, pale blue and white VW Microbus with gray vinyl benches. Along with its dirt and grime and black ice clinging to its undercarriage, it fit in well with the winter landscape. The best part of the bus was the turn indicators. Incredibly, whenever the driver flipped the turn signal next to the steering wheel, an eight-inch, ruler-shaped stick would obediently snap to attention, flipping up and out from its hidden perch in the pillar just behind the front doors on whichever side the vehicle was to turn. I never tired of seeing that mechanical turn signal operate. As soon as Mrs. Brasich’s class was over, I would race outside from the huge, old stone mansion that served as the school for children of diplomats to find the bus in the driveway and secure my seat behind the driver to have the best view of the indicator. The driver, Raday, a small man who was usually, though not always, in a good mood, sometimes would let me inspect the flipper up close while he would operate it from inside. One time the driver’s side flipper wouldn’t work and Raday started to pull it with his hand. “My dad,” I said, “always tells me never to force something. If it isn’t working, there’s a reason.” Raday, who by this time was pounding the side of the vehicle, didn’t seem to appreciate the advice coming from an eight-year-old. I don’t know if Raday ever remembered my dad’s advice, but it stuck with me the rest of my life. Things work or don’t work because of something else, so try to find out, if possible, what that something else is.

The school bus drive to my home from the International School was fifteen minutes at most. When we turned from Topcidarsko Brdo Circle onto Tostoljevska Street, I gathered up my books and papers, knowing I was only a minute away from home. Our house was located on a small cul-de-sac, Krajiska Street, opposite a wooded area. But that afternoon, as Raday turned to pull the microbus off the road and into the small woods on the left, I could see that everything was not quite right. As I got out and Raday began the careful exercise of backing the vehicle into Tostoljevska, I saw immediately that the sidewalk and high fence surrounding my house were covered with graffiti that included (in English) “Yankee go home” and “Lumumba,” and something that ended with “CIA.” I looked around, a little confused and concerned, as Raday drove the vehicle off, evidently not noticing what I had seen, because he presumably was focusing all his energies on backing out into the busy Tostoljevska Street. Two policemen in their long gray coats were talking to each other nearby, not an unusual sight for this area of town that housed many senior Communist Party functionaries. I hurried over to the rusted iron gate and pressed the doorbell, anxious to get inside to something more familiar and out of the January cold. But as I stepped back from the gate I could see the front of the house, the main floor of which sat up like a second floor with the basement and garage level underneath. Most of the front of the house—my house!—had almost all its windows broken, as if it were abandoned and no one was living there anymore.

When nobody came out, I shoved the gate with my shoulder and despite its rusty resistance it somehow opened. I stood there and stared into the cobblestone driveway below the house. I could see shattered glass everywhere. Instead of turning to my left to make my way up the stone staircase to the main entrance, I walked farther along the driveway and could see that not just some, but almost all the windows on the right side of the house were broken and the driveway littered with rocks that had bounced back off the stone siding of the house. Now far more scared than surprised, I ran up the stone stairs to the big, wooden front door and pounded on it to get inside. My mother, holding one of my two-year-old twin brothers in one arm, opened the door with the other. “What happened here?” I asked. And she responded calmly: “Chris, you won’t be playing outdoors today.”

What had happened on that day in January 1961 was that the Congolese leftist leader Patrice Lumumba had been killed at the hands of the CIA—a suspected targeted assassination that was finally confirmed as such years later. His assassination was a cause célèbre throughout the world, especially in communist countries, where he was seen as the vanguard of a new wave of communist expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. And what happened at 2 Krajiska Street in that heavily wooded suburb of Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where my father, the embassy’s political officer, lived with his wife and five children was that an angry Yugoslav student mob, presumably with the knowledge of the Yugoslav communist government under Tito, had marched to a house they (somehow) knew to be occupied by an American diplomatic family, chanted epithets, scrawled chalk slogans, and threw rocks until the police, who had apparently stood by, finally chased them away.

But what did not happen was any sense of panic in the Hill household that afternoon. My father came home to see how we were doing. As if to explain that nothing much had really happened at our house, he told me what had been going on at the Belgian embassy that day. A mob broke into the Belgian compound, located just a few blocks down from the American Embassy, and threatened to come up the main stairway inside the building before the Belgian ambassador, wielding a pistol, yelled to the crowd from the top of the stairs: “Ça suffit!” That’s enough! They left. My father enjoyed telling that story that night as he sat in the living room next to the fire, making his way through his usual evening pack of cigarettes. I’d often sit with my parents at night, getting my dad to tell me about the embassy while they both had their martinis, and I wondered how anyone could drink such a thing (though I did always lay claim to the olives).

My father had a special affinity for Belgians, having served his first assignment in Antwerp immediately after World War II, and admired them for the suffering they had endured in that conflict. Dad explained to me who Lumumba was, and why the connection with the Belgians, and for that matter the connection with Tito’s nonaligned Yugoslavia. “Everything has a reason,” he always explained. “Our task is at least to try to understand what that reason is, even if we don’t agree with it.” I couldn’t understand why a Yugoslav mob was attacking our home over something we obviously had nothing to do with. “Well, not everything has an easy explanation,” he said, as if to negate what he had just explained. “We’d probably have to talk to them.”

“Talk to them?”

“Of course. How else would you find out what they are thinking?”

I don’t remember my father ever telling the story about the pistol-wielding Belgian ambassador again. It just wasn’t that big a deal. Stories like that had a short life span in the Hill household. We would get on to the next issue quickly.

Late that afternoon my mother was still dealing with some remaining shards of glass that had become stuck in her hair-sprayed hair when she had dropped to the glass- and stone-littered floor of the living room to shield Jonny and Nick. Embassy carpenters came the next afternoon to repair the windows (with my assistance in the form of passing them their cigarettes). Apart from those two policemen, who had seemed more interested in their own cigarettes than in protecting our home, there was no additional security and no routines altered or created. My father went to work the next day. I went to school, after the usual argument with my mother about what to wear to my third-grade classroom. I do not remember my parents ever talking about the incident again. It never became part of family lore. I talked to them years later, but it fell to me to jog their memories with my own.

Just two and a half years later, in May 1963, the seven Hills were living in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. François Duvalier had just declared himself president for life, and from our second-floor porch, which had a view overlooking much of the city, I could see fires and hear gunshots. As luck would have it, my dad, the embassy’s economic officer, was the duty officer that week, meaning that he would make frequent trips to the embassy in the dead of night to check on telegram traffic that required immediate attention. This night he had gone to the embassy at 11 P.M., but now at 1 A.M. had still not returned. My mother radioed the marine guard (there were no phones) and was told he had left an hour earlier to make the twenty-minute drive home in an embassy car. She woke up my older sister, Prudy, and me to explain the situation, and we sat on the upstairs porch, our mother with her cigarette, and I with my worries.

He soon returned, to our great relief. He explained that he had been ordered out of the car at gunpoint by Duvalier’s not-so-secret police, the dreaded Ton Ton Macoutes, and held there for some thirty minutes while the TTMs decided what to do with him and his embassy driver. The next evening Mother and Dad told me the situation was deteriorating, that we all might be evacuated, but wanted me—I was ten years old—to know that we had a revolver (with five shots) in the event it was needed. Dad showed me how to aim and fire, while I focused on the fact it had only five chambers and not the six that I assumed every revolver had. “Don’t use it unless you have to,” my mother helpfully told me.

Just a day later my dad came home to tell us that all families were being evacuated and that we needed to pack. “Where are you going to be?” I asked him anxiously. “I’ll be fine,” he told us.

The next morning we were at the airport, boarding a chartered Pan Am flight bound for Miami. My dad, and other Foreign Service dads, stood on the tarmac as we made our way up the stairs. He was waving at us, telling us all to take care of our mother, who was holding on to Nick and Jonny, now four years old, while my two sisters, Prudence and Elizabeth, and I followed. He was still waving at us when the plane pulled away. I was so struck by the fact that if he was worried about anything, he sure didn’t show it.

2

PEACE CORPS

Eleven years later, in 1974, during my senior year at Bowdoin College, I knew I wanted to serve my country. The military draft was over. I decided to join the Peace Corps. Many Foreign Service officers trace their first jobs in diplomacy to their decision to answer President John F. Kennedy’s challenge to spend part of their lives working in the developing world. In October 1960, at 2 A.M., in what he called the “longest short speech” he had ever made, one given to a University of Michigan crowd of five thousand, President Kennedy told students that on their willingness to perform such service would depend “whether a free society can compete.” Generations of Americans joined the Peace Corps filled with a sense of Kennedy’s idealism and many returned with an even stronger dose of realism about what we encountered, and how we needed to manage—and sometimes not—other people’s problems. Whenever I am asked what my favorite Foreign Service job was, I invariably answer that it was my time as a Peace Corps volunteer, the position from which I entered the Foreign Service.

I waited a few weeks before receiving an offer to join a credit union project in Cameroon, West Africa. A few weeks after graduation I was in a credit union accounting training course in Washington, D.C., and on August 11, a day after my twenty-second birthday, with twenty other nervous and excited volunteers I boarded a flight from New York City to West Africa. The Pan Am Boeing 707 stopped at every coastal capital on its way to Central Africa. On the fifth stop, we arrived in hot and steamy Douala, Cameroon. We staggered down the stairway off the airplane into sheets of warm rain and headed to the terminal, where we collected our bags and went through customs, all the while wondering whether we could get a flight the next day to go home. A rented bus whisked us off to a hotel for late-night briefings by an endlessly cheerful Peace Corps staff. The next morning we got on that same dripping-wet bus and headed to a small airstrip in the town of Tiko to board a Twin Otter aircraft. It groaned audibly as it somehow managed to lift off the dirt and muddy runway and begin the one-hour trip to Bamenda in the highlands of the Northwest Province of Cameroon, where the temperatures were far more comfortable than in the coastal south. Our three-week training took place in a Catholic mission where we were housed in a two-room, whitewashed, cinder-block building, ten cots jammed into each room. We had our meals in a similarly austere cafeteria, where we received tips in Cameroonian culture and the basics for communicating in Pidgin English. At the end of the program I was assigned to supervise the credit unions of Fako Division in the Southwest Province, so I packed my bags for the trip to the town of Buea.

Buea had been an administrative capital in the latter half of the nineteenth century, during Germany’s ill-fated colonial era, which came to an abrupt end at the conclusion of World War I, when Germany lost its entire colonial empire to the French and the British. The town is located some 3,500 feet up on the slopes of Mount Cameroon, a volcanic peak that rises from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, the Bight of Biafra, to reach 13,270 feet. With its cool and pleasant weather, albeit with a long rainy season, it is easy to see why the Germans chose Buea at the turn of the century as an administrative capital for its vast plantation system in “Kamerun.” The plantations, which were mostly within one hundred miles of the Cameroon coast, produced rubber, palm oil, bananas, and, in one plantation along the side of the mountain, tea.

Signs of the Germans’ fifty-year stay were visible throughout the town, but especially in the form of the occasional two- and even three-story terraced stone buildings with red metal roofs that seemed so out of place in the lush green natural scenery.

Another volunteer, Jim Wilson, and I arrived there on the first day of September, having survived an eight-hour trip in a Peace Corps Land Rover. The roads in Cameroon would be familiar to anyone who has been to West Africa: a laterite clay, hard almost to the point of feeling like cement in the dry season, but soft like tomato soup during the rainy season. Four-wheel-drive vehicles used in rural Cameroon in the mid-1970s bore no relation to those parked in front of hotels today in Vail or Aspen, Colorado. The shock absorbers seem to have been left out of the undercarriage and a ride of longer than an hour made one feel like a jackhammer operator. Our driver seemed to be in constant road races with the “bush taxis,” Peugeot 404 station wagons that seated nine passengers—two in the front, four in the second seat, and three people stuffed in the rear—and would carry them between towns. Luggage on those taxis (which included live goats and chickens) was stored on roof racks made locally of crude metal and covered with garish signage to encourage repeat customers. The names of the taxis painted on the front of the roof racks were quite varied, often a line from the Bible, or a movie character (“007”), or sometimes just a philosophical expression that the proud driver may have been inspired to make up himself, such as (my favorite) “Man Must Die.”

Getting out of our Peace Corps vehicle was a welcome moment indeed. The driver helped pull our bags out of the back of the vehicle, wished us good luck and told us not to drink the water, and sped off. Jim and I looked at each other and then at our house and our waiting motorcycles sitting against the side of the house. A neighbor who had been watching over the property since the last volunteers had left a few months before emerged from a nearby house with our keys. Our house was made of cinder block and cement and sat incongruously in the midst of a patch of five-foot-high grass off a dirt road. With occasional running water, it was the lap of luxury for a Peace Corps volunteer, a cheerful thought I conveyed to Jim as we surveyed the mauve interior walls and the ubiquitous spiderwebs and, a first for me, a two-inch-wide ant column that had effortlessly marched its way under the front door to what presumably had been a feast of insects inside. Groups of small children started emerging from the tall grass to stare at us, a sight they never lost interest in during the two years we were there. There wasn’t any furniture, but Jim and I used our Peace Corps allowance to build wooden bed frames for our foam rubber mattresses (which we both decided we didn’t want to place directly on the floor) and to buy a few chairs and straw mats.

The best part of the house was its roof. Made of corrugated tin, it stubbornly, albeit loudly, withstood the pounding monsoon rain. Buea had 265 inches of annual rainfall, most of which fell during the summer months through the end of September. That first night in September, with the dry season still a few weeks away, the rain came down on the tin roof in a deafening torrent that I thought would punch holes through it. In the morning, however, a bright sun was up in a cloudless sky, the grassland slopes of Mount Cameroon had become an emerald green, and every insect in the world, it seemed, along with a few newly formed columns of ants, seemed hard at work on the cement stoop or nearby in the thick, green tall grass.

I was assigned to the Department of Cooperatives, under the Ministry of Agriculture, with duties to serve as a credit union field-worker. Catholic priests from the Netherlands had introduced credit unions about a decade before. They had studied the local “Njangi” savings societies, a system of monthly savings against an eventual payout of everyone’s savings. Thus if each person saved a dollar a month and there were twenty persons in the group, that person would, every twentieth month, receive twenty dollars, which, less the funding for food and drink for the monthly party, was a substantial payout, almost like winning the lottery. The priests, carefully building on the Njangi system, created a rudimentary but effective standardized bookkeeping system that allowed people to take loans against their savings or those of a cosigner. The Cameroonian government supported the program and had asked the Peace Corps to send volunteers to help supervise the credit unions.

Credit unions were often the only access to credit that anyone had. And even though the word microcredit had not yet become the subject of Nobel Peace Prizes, loans from tiny credit unions in places were instrumental in helping people create small businesses (foot-pump sewing machines were a popular loan request), buy schoolbooks for their children, and replace thatched roofs (the smells and sight of which bore no relation to thatch roofs in the English countryside) with shiny corrugated metal.

My job was to get to each credit union over the course of the month to check the loan balances, tie up the individual accounts with the general accounts, meet the board of directors, and otherwise make sure that nothing unusual had taken place. The Peace Corps gave me a Suzuki 125cc dirt bike. It was large by local standards, and with its four gears and another four lower gears, activated with the click of one’s heel, it could climb the steepest trails even with Mr. Timti, my Cameroonian credit union trainee, holding on to the rear seat for dear life.

In some villages, especially those up on the mountain, my arrival on a motorcycle was not so much an important event as it was the only event happening in the village that day or even that week. While most adults had at some point been down the mountain to the market towns of Tiko and Muyuka, most of the children had not. Thus dismounting the motorcycle also involved clearing a path to escape the circle of kids that would form around the bike, some interested in the machine, others simply fascinated by my white skin and determined, for a start, to cure me by rubbing it off my hands.

After a meeting w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Prologue

- 1. Early Diplomatic Lessons

- 2. Peace Corps

- 3. First Mentor

- 4. A Force of Nature

- 5. Frasure

- 6. A Peace Shuttle

- 7. Unfinished Business

- 8. On to Geneva

- 9. “Your Beautiful Country”

- 10. Kosovo: “Where It Began and Where It Will End”

- 11. Unfinished Peace

- 12. The Safe Room

- 13. Patterns of Cooperation

- 14. Calling an Audible

- 15. Plastic Tulips

- 16. Heart of Darkness

- 17. Showing Up

- 18. Breakfast with Cheney

- 19. “That’s Verifiable”

- 20. Global Service

- 21. Taking the Fifth

- 22. The Longest Day

- 23. Winding Down the War

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Outpost by Christopher R. Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.