![]() BOOK TWO

BOOK TWO

WALKING THE

PATH OF

POWER![]()

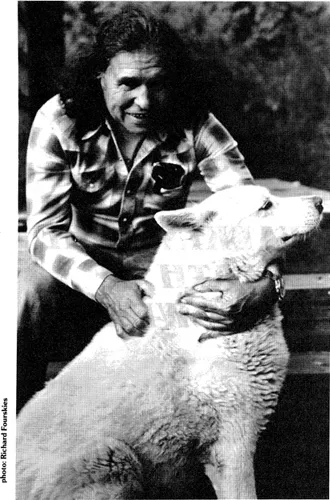

I say Shasta is a medicine dog because of the way we found him.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

FINDING

VISION

MOUNTAIN

We were back at Sun Valley, and the few folks who had followed us squeezed into whatever space they could make for themselves. There were times, I guess, when we felt we were packed in like sardines, in a couple of little trailers.

We had learned a few hard lessons about organization from the early Bear Tribe attempt; so starting up again, I think we knew a little bit better how to go about things. Personal responsibility would have to be a major issue. Controls would be a whole lot tighter, and as it turned out, it’s a good thing that we stuck to that philosophy. For one thing, the fellow who originally did the printing of Many Smokes on our press was really inventive. He had an idea that the press could be used for several different jobs simultaneously. One, of course, would be to turn out the issues of Many Smokes; the other, which he neglected to tell us about, was a very amateurish attempt to counterfeit twenty dollar bills.

We caught him at that, and we sent him on his way. The art work on his phony money was really a poor job; even a five year old kid, I think, could have told those bogus bills from the real McCoy.

In January of 1972, Marlise James came out to join the tribe. She’d finished writing THE PEOPLE’S LAWYERS, and we had a lot of plans for reorganization. She had come out at just the right time, I don’t mind telling you; it was during that winter that I was experiencing my first and only misgivings about the fulfillment of my vision. When I thought about the Bear Tribe of my vision, and I looked at the reality of the kind of people who had come to the first base camps, my spirit seemed to dampen. That first experience had cost me a lot of energy, as well as all of my money. Thanks to Marlise, though, and to all the other good people I had around me, we kept the dream going.

The preceding fall, we had an offer for the Sun Valley Trailer park. It came through that spring. I was glad to have a chance to get rid of it. I didn’t like running a business, chasing after people for rent money, keeping them from stealing my furniture. It was getting in the way of what I really wanted to do. I traded off my equity for eleven acres of land near Los Gatos, California. It seemed like a good move at the time, until we arrived at the new land and discovered that it sat on a major earthquake fault line.

I still had to spend most of my time up in Reno. We had kept a couple of trailers up there, and with Marlise, Nimimosha, and the others I mentioned, we printed Many Smokes at the trailer court.

After being with the Bear Tribe for a while, Marlise James was adopted as a full member in a ceremony at Pyramid Lake. Later, she would become my medicine helper with the Bear Tribe, and from this time on I’ll call her Wabun. Wabun, to the Chippewa people, is the Spirit Keeper of the East. Wabun is the spirit of wisdom and illumination; the messenger of spring and awakening growth.

It became apparent, at that point, that in order to get a firm financial base for the Tribe, we would have to be on the road again, this time selling an inventory of Native craft items.

So that spring, we set out on what is called the “pow wow circuit”, going around to the various Indian festivities, selling crafts, books, whatever we could get our hands on.

We didn’t have much to sell in the beginning; I had about $500 worth of inventory, a few rings, and mostly bows and arrows that we’d bought awhile back from the Cherokee people. We started out with practically nothing, hitting the Indian arts and craft shows, and, of course, while we were at them, selling copies of Many Smokes.

On the pow wow trail, we travelled all over the country again; we camped out, always moving. Most of the money that we took in we reinvested in more and better stock items.

We tried to hit all of the annual Indian festivities ... the dances, the ceremonials which were open to the public. Most tribal groups put on a pow wow once a year, and there are hundreds of different ones to go to, both in the country, and in a lot of the big cities. At a pow wow, traditional dancers dress up in their Native costumes. They travel themselves, sometimes thousands of miles, to get to the festivities. There are drummer groups from all over the nation: and dancers compete for prizes in a lot of different categories. There is traditional dancing, which is getting more popular all the time; there is Indian fancy dancing; fast dancing; slow and fast war dance categories; women’s traditional dancing; and dancing contests, even for groups of little children.

The pow wows are great things for the people. Whole families can get together and have a carefree time. It’s quite a change, for a lot of my brothers and sisters, from the bleak existence they live through day-to-day on the reservations or in the cities.

Going to the pow wows also helped me get over the bleakness that I felt in my soul because of the things that had happened to the Bear Tribe in California. For three years, on and off, Wabun and I rode the pow wow circuit. I knew, at first, that this was part of my hibernation period, but I felt that at least I was able to do something constructive. We were getting financial resources that would enable the tribe to re-emerge at a later date.

I know that this travelling also helped Wabun understand many facets of the Native culture today, and prepared her to take her place as my medicine helper. When Wabun joined the Tribe she knew very little about the Native culture ... and the pow wows, the shows, and the people that we met at them gave her a crash course that no college could ever offer.

As we travelled I met many old friends that I had not seen for awhile, and their acceptance helped me to feel better about life. We also made many new friends — people like Larry and Lee Piper of Seattle, and Joyce and Richard Rainbow of Tuolumne, California — who gave me new spiritual insights and ideas.

We even helped to sponsor a couple of Indian Shows in the Sacramento area, and that experience, though we didn’t know it at the time, would prepare us for other kinds of gatherings that we were to sponsor later on.

Some of the first pow wows we went to were near Los Angeles. While we were in the area we would always stay with Jeannie and Bob Babcock, who I had known from the old days of the Los Angeles Indian Center. It was real good to see them again. Bob, who we called “The Old Buzzard”, has always been like an uncle to me. He’s a real old-timer, with a great love for people, and for animals. They would always have dozens of cats in their home, and dozens of homeless cats that would hang around outside, eating the food that they provided. Uncle Bob has even had a couple of raccoons for pets there in the big city. Jeannie and Wabun became good friends, and Jeannie taught Wabun a lot about the hospitality that Native women always showed to guests. Native women serve their guests lavishly and unobtrusively, and I think Wabun, with her New York feminist background, would have had a hard time learning this from anyone who did not have the grace, understanding, strength and dignity that Jeannie did in her manner of living, and of service.

From the Los Angeles area we began to go to other California pow wows, then to some in Nevada, Montana, Oregon and Washington.

Since most of the pow wows were outdoors, we’d find ourselves a shady spot and spread a blanket on the ground. We’d display our merchandise on the blanket. Sometimes we’d get a spot for free, but most of the time we would have to pay a permit fee.

A lot of the pow wows had rodeos going on, and sometimes there’d be big Indian ceremonial shows to watch. At Indian arts and crafts shows in Los Angeles and other big cities there would be 100 to 150 dealers in Indian arts and crafts, and at those shows I would get myself a booth in exchange for an ad in Many Smokes. I’d sell the magazine to all the dealers, as well as the visitors who walked around. The magazine proved to be a boon for everyone involved; it brought in some money for me, and it listed all forthcoming pow-wows for the dealers.

We bought turquoise and silver jewelry, I remember, just before it became extremely popular; there were a few years there, when everybody wanted to buy it. So we got in on the ground floor; we had a really good supply. We managed to put away a bit of money from the sales.

One year, I remember, we spent every bit of our cash except twenty dollars on turquoise jewelry; we bought it from Native craftsmen down in Gallup, New Mexico. We set out on a selling trip, from Gallup to Washington D.C., with a credit card for gas, and that twenty dollar bill. We did so well on that trip, selling jewelry at the pow wows, that we actually came back with a nice profit.

The pow wow years were fun and exciting, even though it was hard work a lot of the time. In between shows we would stop in every book, novelty, and jewelry shop we came across, to try to wholesale some of our inventory. We almost felt like our car was home. We’d travel in it — often long distances in short periods — sleep in it and often eat in it. I was so tight with money during this time that Wabun nicknamed me El Cheapo. But I knew we had to build up a good reserve in order to eventually get land and allow the Bear Tribe to re-emerge.

There were many times when we were touched by the generosity of people we would meet at a pow wow who would take us into their homes and feed us, and treat us like true brothers and sisters. There were other times when the children who sold Many Smokes touched us deeply with their love and generosity. Wabun remembers one young man at the Oil Celebration in Poplar, Montana, who worked harder all weekend than any other kid. At the end, he used all the money he had earned to buy a gift for his mother. Wabun was so touched that she gave him a beautiful belt buckle for himself.

We met a lot of sharpies, too, who helped us develop our skills in bartering and trading. I learned in Navajo country to let Wabun do the dealing. It is the women there who make the financial decisions, and they seemed to have more respect if they were dealing with another woman trader.

Often during this time we encountered nature in all her beautiful, and powerful, aspects. We did one pow wow in Ft. Collins, Colorado, just at the foot of Pikes Peak. Every day at four in the afternoon, the thunder beings would come to visit. We were in a booth built for the occasion by the Army Corps of Engineers. At 3:30 we would begin to put all of our merchandise in boxes under the counter so it would not get wet. One day the wind was so strong it blew the whole booth over, with Wabun and the merchandise still in it. So much for Army engineering.

A couple of times, going across the Plains states, we outran tornadoes — a good thing, since we had a lot of the inventory on a rack on top of the car, with only a tarp for cover. We just missed flash floods a few times in the high desert. Our medicine was good.

Often we would just spend our drives marvelling at the beauty of the mountains, the deserts, the ocean, the clouds, the sunsets, and the sunrises. Seeing all of this beauty healed me as nothing else could.

All of the time, when travelling, we made an effort to meet my Native brothers and sisters, and to exchange our ideas. At the same time, in Many Smokes, we would cover local Indian stories wherever we went.

One Indian story we covered at that time was a very big one. It was the Native occupation of Wounded Knee, in 1973. The occupation took place on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, which is primarily a home for the Oglala Sioux. Although most people have heard about the takeover, not too many people really know what went on there. So, I’ll tell you some of it from my viewpoint.

In 1890, the U.S. Government slaughtered close to three hundred Sioux at Wounded Knee. That was a very famous, or infamous, massacre, which took place after the Sioux nation had signed three major treaties, each time losing more of their reservation land. In 1973, about the same number of Sioux, three hundred, went back to Wounded Knee to make another stand.

The Traditional Oglala, along with members of AIM, occupied a trading post area at Wounded Knee. Many of the people there travelled hundreds of miles in order to join what would soon be called the Independent Oglala Nation. The group, once established in Wounded Knee, were quickly surrounded and besieged by U.S. Government forces. U.S. Marshals, FBI people, State police ... all came heavily armed with automatic rifles, with armored personnel carriers, even helicopters. The government decided not to make an assault on the trading post; I guess they figured another massacre at Wounded Knee might be bad press. Instead, they decided, they would try to starve the renegades out. They barricaded the area and confiscated any food, fuel, or medical supplies from people who had reason to go past their blockades. In addition, they placed U.S. marshals on a hilltop above the trading post.

In spite of all this pressure, the people who had taken over at Wounded Knee managed to hold out until they finally came out to try for peaceful negotiations. For almost two months then, in 1973, the small patch of land known as Wounded Knee was Indian Territory.

There were a lot of reasons for the Native takeover, and they were very complicated. Since 1868, the land on the Sioux Reservation had been constantly whittled away by government manipulation. By the 1970’s, Pine Ridge, like so many other reservations, was a checkerboard of Indian and non-Indian land.

There are three million acres at Pine Ridge, and by the early 1970’s only half of that land belonged to Native people. A half-million acres were owned by the BIA-supported Tribal Government, and a million acres were owned by white ranchers and farmers.

Employment was practically nonexistent for Oglalas, and most of them were so poor that they were forced to lease their land to the white ranchers, at prices which were set by the BIA. Poverty and Tribal Government brutality had literally begun to force the traditional Indians to their knees, when they finally fought back.

The Tribal Government, which was formed by the 1934 Reorganization Act, was controlled by a group of people who were not acting in the best interests of all of the people. Jobs on the reservation were given out to favorites only. This group was backed by a goon squad comprised of Indians and whites who were armed with clubs, tear gas, and guns. Whenever anybody spoke out against policies, they were badly beaten.

Conditions became so bad that, by 1972, a lot of traditional leaders were making public protest speeches and in general, bucking the established system. They paid for their efforts; many of them were badly beaten. A lot of their families were threatened, and some homes were firebombed.

In February of 1972, an Oglala from the Porcupine Community named Raymond Yellow Thunder was murdered by two white men in Gordon, Nebraska. At first badly beaten, he was stripped naked and thrown into an American Legion building during a dance. The two men then dragged him back outside, beat him some more, then stuffed him into their car trunk. His body was found two days later. The two men responsible were charged only with second degree manslaughter, and both of them were released from jail without paying any bail.

When Yellow Thunder’s family protested to the BIA, they were told to keep their mouths shut. Both the BIA and the Tribal Government refused to help them find out why justice was not being done. So the family, angry and desperate, called in leaders from AIM to launch a full investigation.

From that time on the violence increased; there were more beatings, there were more murders. In January of 1973, another Oglala named Wesley Bad Heart Bull was murdered in Buffalo Gap, South Dakota. His alleged killer, Darald Schmitz, was arraigned on manslaughter rather than murder charges. When that happened, AIM led a protest demonstration in Custer, South Dakota.

Finally, in February of ‘73, things had reached a breaking point, with Indians being abused and nobody listening to them. The traditional Oglala leaders met at that time with leaders of AIM, in the community of Calico, and from there they moved to Wounded Knee, hoping to gain national recognition. Their major demand was that the U.S. Government honor the treaty of 1868, which they’d made with the Sioux Nation. That treaty, signed at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, had set up the Sioux Nation to include all of western South Dakota, and close to half of each of North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska. Compared to that amount of acreage, the Pine Ridge reservation was like a speck of dust. In addition to that designation of territory, the 1868 treaty promised that the Sioux would be the keepers of all of the animal, mineral, water and plant kingdoms on their land, and that they would be given the opportunity, by the government, to always maintain their self-sufficiency.

Let it be known, the manifesto of the Independent Oglala Nation read, during the 1973 takeover, that the Oglala Sioux people will revive the treaty of 1868 and that it will be the basis for all negotiations...

We are a sovereign nation by that treaty . . . We intend to send a delegation to the United Nations...We want to abolish the Tribal Government...

The traditional people were already a nation before the white man ever came...all we are doing is reminding the U.S. Government of that...

I travelled down to Wounded Knee, along with a writer friend of mine, Marcus Damien, to see what was really going on. The media, at that time, was portraying the takeover as a move by a bunch of hotheaded radicals. I knew that was not true.

When we reached Hot Springs, South Dakota, outside of Rapid City, we were told there were no motel rooms available. At ...