- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

We all know “there’s no such thing as monsters,” but our imaginations tell us otherwise. From the mythical beasts of ancient Greece to the hormonal vampires of the Twilight saga, monsters have captivated us for millennia. Matt Kaplan, a noted science journalist and monster-myth enthusiast, employs an entertaining mix of cutting-edge research and a love of lore to explore the history behind these fantastical fictions and our hardwired obsession with things that go bump in the night.

Ranging across history, Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite tackles the enduring questions that arise on the frontier between fantasy and reality. What caused ancient Minoans to create the tale of the Minotaur and its subterranean maze? Did dragons really exist? What inspired the creation of vampires and werewolves, and why are we so drawn to them?

With the eye of a journalist and the voice of a storyteller, Kaplan takes readers to the forefront of science, where our favorite figures of horror may find real-life validation. Does the legendary Kraken, a squid of epic proportions, really roam the deep? Are we close to making Jurassic Park a reality by replicating a dinosaur from fossilized DNA? As our fears evolve, so do our monsters, and Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite charts the rise of the ultimate beasts, humans themselves.

Ranging across history, Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite tackles the enduring questions that arise on the frontier between fantasy and reality. What caused ancient Minoans to create the tale of the Minotaur and its subterranean maze? Did dragons really exist? What inspired the creation of vampires and werewolves, and why are we so drawn to them?

With the eye of a journalist and the voice of a storyteller, Kaplan takes readers to the forefront of science, where our favorite figures of horror may find real-life validation. Does the legendary Kraken, a squid of epic proportions, really roam the deep? Are we close to making Jurassic Park a reality by replicating a dinosaur from fossilized DNA? As our fears evolve, so do our monsters, and Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite charts the rise of the ultimate beasts, humans themselves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Monsters by Matt Kaplan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Giant Animals—Nemean Lion, Calydonian Boar, Rukh, King Kong

“Rodents Of Unusual Size? I don’t think they exist.”

—Westley, The Princess Bride

In the midst of the darkened jungle, it sniffs the wind and catches the scent of a lone human not more than a mile off. Saliva dripping from its sharp fangs, it eagerly sets off in search of its prey. There is but a sliver of a moon in the sky, but this doesn’t matter to the creature’s inhuman eyes. The scent grows stronger and the beast slows its movements to a crawl as it silently stalks its prey from the depths of the forest. Then, in a split second, it springs into action. Claws rend flesh in a single swipe. Blood gushes forth. Jaws sink deep into the shoulder, snapping bones as if they were twigs. In an instant, the human is dead.

A lion might not look particularly monstrous while sitting caged in a zoo, but make no mistake, a midnight encounter with one in the wild would change that perception in a hurry. For most people today, there is not much reason to worry about being hunted.4 Every now and again the story of a lone backpacker being eaten by a large predator makes its way across the media, but the reality is that predators capable of eating people are mostly endangered and often terrified of even coming close to us.

Yet it was not a long time ago when wild animals were a regular cause of death. In the 1800s, rain forests weren’t ecoholiday destinations where tourists could be found snapping photographs of toucans and orangutans. They were jungles where bloodthirsty beasts waited to eat the unwary. Explorers who entered such places often did not come back. And that was in the 1800s. Ancient humans had it much worse.

The Aché people of Paraguay hunt with bows and arrows to this very day and, unlike humans in most other parts of the world who sit alone at the top of the food chain, they are hunted. Jaguars share much territory with the Aché and eat many of the same small mammals that the Aché depend upon to survive. However, jaguars also readily kill the Aché themselves, inflicting an 8 percent mortality rate on males in the population. For comparison, consider the fact that in 2002 the World Health Organization calculated a 2.1 percent mortality rate from road traffic accidents, a 2.2 percent mortality rate from malaria, and a 9.6 percent mortality rate from strokes. It is mind-boggling to think that jaguars could bring a somewhat similar loss of life to males in a population as strokes do in the developed world today, but given that the Aché have the same sorts of rudimentary tools that most of our ancient ancestors had, we have to assume that this was the way life once was.

Yet far beyond the issue of not having advanced equipment for a journey into the wilderness, early humans first exploring the wild had precious little information on what to expect there. One of the first encyclopedic works on the natural world was written by the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, and he wasn’t even born until AD 23. Ancient adventurers would have had only tales passed by word of mouth to inform them of what to expect when they stepped beyond the safety of their town or village.

Let’s face it, word of mouth distorts, but that was not the only problem. In jungles, dense vegetation blocks most lines of sight and forces visitors to make sense of fleeting glimpses of movement, strange animal calls, and mysterious prints in the mud. There was also the thrill and fear. Adrenaline dramatically alters perceptions. Imagine the first reports: “The beast was as large as a house!” “Its teeth were as long as daggers!” “I once caught a fish this big!” You get the idea. It is not hard to see how otherwise ordinary animals transformed into monsters of legend.

With human exploration of the natural world in its infancy, the first environments of mystery encountered were the wild spaces just beyond town. Thus, it is unsurprising that some of the earliest monsters in human history are merely fierce animals with extraordinary characteristics.

Among these was the Nemean lion, a great cat born to Typhon, the godlike creator of monsters, which was later nurtured by the goddess Hera. A description of this beast as a fierce man-eater with skin that could not be harmed by mortal weapons has been attributed to the Greek scholar Apollodorus (180–120 BC). In his account, the monster is hunted by the hero Hercules, who must slay the beast as the first of his great labors. His tale reads: “And having come to Nemea and tracked the lion, he first shot an arrow at him, but when he perceived that the beast was invulnerable, he heaved up his club and made after him. And when the lion took refuge in a cave with two mouths, Hercules built up the one entrance and came in upon the beast through the other, and putting his arm round its neck held it tight till he had choked it.”

Exactly how big the lion actually was is not mentioned, but the mythic scene is well depicted on ancient pottery. In these works, the Nemean lion is shown to be as large as Hercules or slightly larger. Hercules was part god and known for being big and strong. So a lion matching him in size would, presumably, have been large too, but only slightly larger than lions that are alive today. To say that the lion was a giant would be wrong. It is never depicted as dwarfing either Hercules or any humans, so we can assume it was merely meant to be a mean and mostly invulnerable beast.

Herakles and the Nemean Lion, attributed to Kleophrades painter. Greek ceramic stamnos, c. 490 BC. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

But some monsters actually were giants. Homer, who lived around 850 BC, recounted a tale in the Iliad of a fierce boar that was unleashed upon humanity. According to the story, there was a king of a Greek city known as Calydon. He was a good king who looked after his people by making frequent sacrifices to the gods, but at one point he failed to properly honor the goddess of the hunt, Artemis. She became angry at this lack of respect and, in a temper tantrum, let her personal boar run wild in the king’s lands.5 Homer describes this boar: “The Lady of Arrows sent upon them the fierce wild boar with the shining teeth, who after the way of his kind did much evil to the orchards of Oineus. For he ripped up whole tall trees from the ground and scattered them headlong roots and all, even to the very flowers of the orchard.”

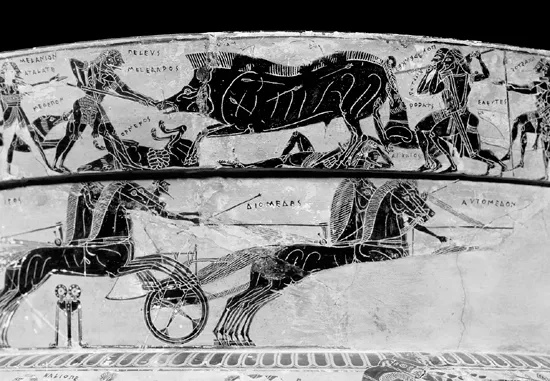

“Shining teeth” indicates that its tusks were large and sticking well out of its mouth, and to be able to uproot tall trees, it must have been enormous. Artwork supports this last claim with Greek pottery revealing a boar as long as more than two men were tall, suggesting that it would have been about a length of 11 feet (3.4 meters).

The Calydonian Boar Hunt, painted by Kleitias. Greek ceramic krater, c. 570 BC. Archaeological Museum, Florence. Scala/Art Resource, NY.

As monsters go, the Calydonian boar and the Nemean lion did not require much creativity. One was just a somewhat large lion with seemingly weapon-deflective skin, the other just a boar that differed from normal animals in its size, strength, and ferocity. All storytellers needed to do was point to the real lions and boars that most Greeks were familiar with and say, “The boar that Artemis released was like that, only bigger and meaner,” or “See that lion? The one that haunted Nemea looked the same, but its skin was invulnerable.”

And while it might not be easy for modern audiences to appreciate why such creatures would have been frightening, consider this: Male wild boars frequently grow to 5 feet (1.5 meters) in length, weigh over 440 pounds (200 kilograms), and their tusks are more than 4 inches (10 centimeters) long. Today, fatalities from boar attacks in Europe are extremely rare, but traumatic wounds are not. The wounds can be easily treated in hospitals, but a few thousand years ago blood loss and infection would cause many encounters with these animals to be lethal. Boars are exceedingly territorial, and before their habitats were significantly reduced, they were a serious menace. With fear of wild boars already present among ancient populations, it would not have taken much for a mysterious call heard in the woods and unexplained fallen trees to be tethered to the presence of a boar of mythic proportions.

As for lions, they were not just the inhabitants of the African savannas. European lions lived in and around ancient Greece.6 To the best of modern scientific knowledge, these were as fierce and as large as the African lions of today. They probably stayed well away from human settlements, but even so, if any lions hunted humans, the stories of such events would have spread like wildfire along trade routes and could have quickly led to the imagining of a terrible beast of legendary size. And the tendency for lions to hunt at night would have strengthened the myth. People living near lion dens would vanish in the night, leaving behind just a smearing of bloody remains. Many lion attacks would have had no eyewitnesses to describe what exactly did the killing. And even if there were witnesses, their eyes would have been mostly useless in the dark. They would have seen glimpses of action, heard roars and screams, and been overwhelmed by fear. An accurate report of what sort of predator had attacked would have been impossible. So the stage was set for normal lions to be transformed into supernatural monsters. This is probably where the concept of invulnerability set in. European lions would have been able to survive a number of wounds before being killed. It is not unlikely that watching a lion continue an attack after being stabbed or shot by an arrow led to the rumor that it was impervious to mortal weapons.7 Even so, could the ancients have actually been right? Could there have really been a lion or boar of mythic proportions?

Larger than life

Many land animals can get really big. The African elephant can reach over 25 feet (7.5 meters) in length, 11 feet (3.3 meters) in height, and can weigh more than 13,000 pounds (6,000 kilograms). Many dinosaurs were even larger. However, big animals leave behind big bones when they die and tend to be conspicuous in the fossil record. Some of these bones could have been interpreted as the bones of predators, particularly if they were found alongside the skull of an extinct saber-toothed cat or cave bear. It is also reasonable to believe that the fossil tusks of one animal, like those of a mammoth or mastodon, were mistaken by the Greeks to be the tusks of a giant boar. Adrienne Mayor’s book The First Fossil Hunters looks at the interactions between ancient people and fossils, and points out that some of these relatives of the modern elephant were once dwelling on the islands in the Mediterranean and that their remains ended up being labeled as having belonged to heroes, giants, Titans, and even the Cyclops.8 There are even some fossil tusks in the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea that are identified as having belonged to the Calydonian boar. Such discoveries no doubt played a part in the conjuring up of giant animal monsters, but what of living animals? Could a particularly large lion or giant boar species have actually been plaguing ancient humans? In the case of the Nemean lion, the answer is an intriguing yes.

The Eurasian cave lion was similar to the lions of Africa and the recently extinct European lions, but it grew as much as 25 percent larger. And it seems likely that it had interactions with ancient humans since it was alive when people were roaming around much of Europe and Asia. Evidence of the lion does not appear in the fossil record much after 11,000 BC, but numerous cultures that are widely thought to have mastered language and some degree of oral storytelling were already in existence at this time. It is possible that these people captured the essence of this great cat in their tales and passed along stories about it through the generations both to entertain and to warn fellow members of the population about dangerous animals in the surrounding environment.

Moreover, 11,000 BC may not have been the actual date when the cave lion vanished from the face of the earth. Just because nobody has found more recent fossils of the species does not mean it did not linger on. The fossil record is a fickle thing and it often does not provide a perfect snapshot of ancient history. Fossils form in regions where sediment can quickly fall on top of an animal after it has died. When lions were common in areas near lakes and rivers, their bones would readily get covered up and preserved. Preservation also tends to be good in caves, where lion fossils are often found. However, as humanity spread across the landscape, and freshwater sources along with caves were identified as valuable places to settle, lions would have been driven away from these places and forced into environments where they would be less likely to fossilize after death. They may have died out shortly after being displaced in this way, but it is possible that some small and isolated populations endured for several thousand years longer, particularly in more remote and less hospitable locations at higher altitudes where humans were not commonly spending time. If this was true, then the Mesopotamians of 6000 BC may well have tangled with some very big cats and had more than the stories of their ancestors to give them nightmares.

Moreover, if isolated populations of Eurasian cave lions did hang on in mountainous regions, this may have increased both their size and their resistance to weapons in some rather fascinating ways. To begin with, evolution drives mammal populations dwelling in colder environments to get larger over time. This has to do with the physics of heat. Small bodies have more surface area relative to their overall mass and lose heat from their cores much faster than large bodies. For this reason, big animals are much less resistant to heat loss and tend to better tolerate cold climates. This is why the Kodiak bears living on the frigid Alaskan islands are so much larger than their closely related grizzly bear kin dwelling in milder climates. It is also why the mammals that survived the various ice ages, like the woolly mammoth, giant sloth, and woolly rhinoceros, grew to such enormous sizes. They were extraordinarily resistant to heat loss.

Whether Eurasian cave lions were in fact driven into the mountains and whether natural selection actually did lead to the already large lions getting larger is of course speculation, but the evolutionary mechanisms that connect cold and size are well known, so the possibility is not mere fantasy. The presence of unusually large and powerful lions in remote mountain areas mixed with the adrenaline-influenced perceptions may well have been responsible for people coming to believe in a monstrous lion.

As for the Nemean lion’s invulnerability, for weapons to have bounced off of its body, as described in Apollodorus’s story, it must have had really tough skin. Is it possible that a lion had such skin?

There is a genetic disease called scleroderma that arises in humans and makes the skin thicken. It is, however, a disease. Those who suffer from it often develop kidney and lung problems that cause a lot of pain. Other animals can develop this condition, but it is hard to imagine scleroderma causing the skin of a lion to thicken to a point where it could deflect an arrow or a sword. Humans who suffer from scleroderma are more fragile than they are invulnerable. Thus, scleroderma as an explanation for the weapon-deflecting properties of the Nemean lion does not make sense. For its skin to have been able to do what Apollodorus said it could, the skin would have had to have been as thick as that of an armadillo.

Could some mutant lion with skin as thick as an armadillo have been around in ancient Greece? Anything is possible when it comes to genetic mutation, where the DNA in an animal spontaneously changes and leads to the expression of physical characteristics that are distinctly different from those of others, but such a lion would hardly have been a threat. A lion with thick armadillolike skin would...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Giant Animals—Nemean Lion, Calydonian Boar, Rukh, King Kong

- Chapter 2. Beastly Blends—Chimera, Griffon, Cockatrice, Sphinx

- Chapter 3. It Came from the Earth—Minotaur, Medusa

- Chapter 4. The Mysterious Fathoms—Charybdis, Leviathan, Giant Squid, Jaws

- Chapter 5. Of Flame and Claw—Dragons

- Chapter 6. Hauntings—Demons, Ghosts, Spirits

- Chapter 7. Cursed by a Bite—Vampires, Zombies, Werewolves

- Chapter 8. The Created—The Golem, Frankenstein, HAL 9000, Terminator

- Chapter 9. Terror Resurrected—Dinosaurs

- Chapter 10. Extraterrestrial Threat—Aliens

- Conclusion

- Sources

- About Matt Kaplan

- Index

- Copyright