![]()

PART ONE (1864):

THE SETTING OF THE TERMS

If England is resolved upon a particular policy, war is not probable. If there is, under these circumstances, a cordial alliance between England and France, war is most difficult; but if there is a thorough understanding between England, France, and Russia, war is impossible.

Disraeli, House of Commons, 4 July 1864

![]()

Trouble in paradise

Britain in 1864 was as confident as America in 1994.FN7 The existential challenges of the previous decade were history: Russian ambition had been bloodily tamed in the Crimean War, India was once again firmly in British hands after the great trauma of the Mutiny and France’s brief technological edge in ironclad warships had been so comprehensively annulled that Lord Palmerston’s wildly over-engineered coastal forts (virtually indestructible, they may still be visited from Cork to Dover) were being called his follies before they were even finished.

There were problems on the peripheries, true: in Jamaica, General Eyre was putting down the rebellion with rather troubling zeal; the rambunctious Irish had bred a violent new group called the Fenians – or was it Feenians? Perhaps it derived from some classical Phenians? – and it seemed possible that the United States, now fully geared-up for war in body and mind, might be tempted to apply to the 49th parallel the same logic which it was remorselessly imposing upon the Mason–Dixon line.

But these were mere details, for mid-Victorian Britain was not only the richest and most potent country on Earth, it also had a matchless sense of how it had become so. Britons had a story about themselves like no one else had. The tale had been gloriously told them by Lord Macaulay, the great historian of British Progress.FN8 In 1864 they were, almost to a man, as convinced as Donald Rumsfeld in 2003 that humanity would soon universally choose the self-evidently superior British ways of personal liberty, constitutional reform and trade’s increase – prompted by a judicious dose of high-tech, low-risk military persuasion where necessary.

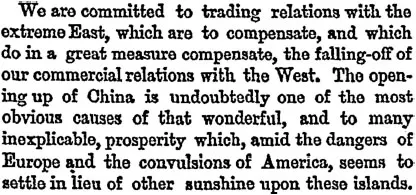

The finest proof of this muscular pudding lay in that vast new market which had been prised open by a short but fiery lesson in the reach of the British Empire and the inadvisability of trying to stem the inevitable march of free trade, even if it included opium.6

And what were the dangers of Europe in 1864? The answer is simple, though perhaps surprising to us, so lost has historical truth become in later myth: Britain was, as a speaker in the House of Commons put it roundly, ‘on the verge of a war with Germany’.7

The poor relations

It seemed ridiculous. Britain was used to looking at Germany as a sort of poor, backward and rather comic relation.

The word ‘relation’ is almost meant literally. Right up until 1914, the newspapers, essayists, cartoonists and even the topmost diplomats of Britain and Germany – men like Bismarck and Lord Haldane – often described the other nation in terms of more or less distant family. Terms like ‘cousins’ or ‘relations’ were common on both sides, even when – often, especially when – the subtext was by no means friendly. No one on either side ever spoke about the French or Russians in this way.FN9

The literal relatedness of the British and German royals was just the visible tip of this strange, deep and mutual feeling that Britons and Germans really ought to be like one another. This sounds very positive, but it also meant, of course, that if they weren’t, something was very wrong indeed: there is no fight like a family fight.

To Victorian Britons, Germany’s role in the future unfolding of the world was clear. She was to sort herself out, unite, and adopt the predestined British ways of her older, wiser and infinitely stronger relation. Protestant Prussia, Britain’s helpmeet in the epochal triumphs of 1759 and 1815, would presumably lead the way, but would then be peaceably merged into a new, British-style United Germany, run by a real parliament. This was the so-called Coburg Plan, beloved of the Prince Consort, himself, of course, a German. After his untimely death, the Queen clove to the Dear One’s vision.

At present, however, Germany remained a hopeless mess of tiny countries, like Thackeray’s comic Pumpernickel, scarce ten miles wide, with its absurd court, its gorgeous but entirely useless officers and its western frontier ludicrously bidding defiance to Prussia.8 This Prussia was the most go-ahead German state, but even Prussia was hardly respectable: The Times warned that marrying Albert’s and Victoria’s own daughter (another Victoria) to the Prussian Crown Prince was making a connection with ‘a paltry German dynasty’.9

If even the Prussian royal house was paltry, Henry Mayhew, co-founder of Punch, could only hope to make the poverty and backwardness of Germany in general imaginable to his readers by comparing it with that most irredeemably wretched of countries, Ireland:

Gadflies in summer never swarmed in such number about a dung-heap; nor vermin infested so profusely the rags of Irish beggars; such greedy parasitical animalcules were never seen in a magnified drop of dirty water; no insects at the time of a ‘great blight’ ever covered the land so thickly, or ravaged it so thoroughly, as the horde of petty swaggering bogtrotter potentates in this miserable, under-fed, and over-taxed – ground-down and used-up – ill-conditioned and well-plucked – luckless, lifeless, spiritless, hopeless, and penniless – befuddled, beleaguered, and benighted old Fatherland, or rather old Great-grandmother-land, of Germany.10

Many Britons, or at least many Londoners, saw the truth of this every day, because London was well supplied with Germans, drawn there by those simple but timeless dreams which still draw foreigners ceaselessly to London: freedom and money.

For most, then as now, it was simply money. Germans in 1864 were so much poorer than Britons that even if they were no longer sold en masse to the British Army, as they had been in the previous century (to the outrage of Irish and American patriots, in whose ballads the despised Hessian hirelings of King George III often figure), British employers could still draft them in another capacity: as cheap labour to keep costs down.

Karl Marx, himself of course a London German asylum seeker, and one kept from penury only by Friedrich Engels’s helpfully intimate connections to the evils of capitalism, fulminated against this example of mid-Victorian globalisation:

Defeated in England, the masters are now trying to take counter-measures . . . secretly they sent agents to Germany to recruit journeymen tailors, particularly in the Hanover and Mecklenburg areas . . . The first group has already been shipped off. The purpose of this importation is the same as that of the importation of Indian COOLIES to Jamaica, namely, perpetuation of slavery . . . No one would suffer more than the German workers themselves, who constitute in Great Britain a larger number than the workers of all the other Continental nations. And the newly-imported workers, being completely helpless in a strange land, would soon sink to the level of pariahs.11

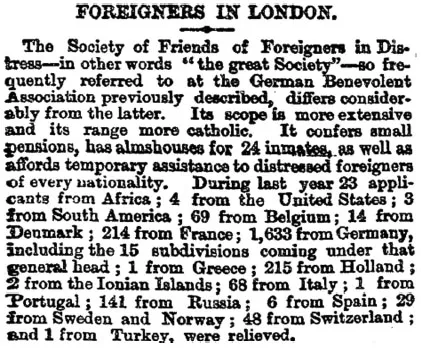

The idea that cheap German labourers outnumbered the workers of all the other Continental nations was not a fantasy of Marx’s. We can see this from a remarkable set of figures given in the Daily News:12

German girls, lured from grinding rural poverty by promises of respectable work in a London paved with gold, were always to be found selling themselves around Leicester Square. Ragged-trousered street-bands of German buskers were such an infestation that the authorities, besieged by complaints from Dickens and Carlyle among many others, tried to suppress them by means of the 1864 Street (Metropolis) Music Act. This failed to stop the impecunious brass players of Germany coming to Britain or entering – ultimate sign of assimilation – the unwritten dictionary of London rhyming slang (‘German bands’ = ‘hands’).

Britons at home thus came across Germans in various not very flattering ways and would have looked down with pity or irritation at yet another ‘thin, under-sized German lad such as we see every day in the streets’.13

These Germans, of course, had some attractive qualities. Their colourful, sentimental Christmas festivities, imported by the late Prince Regent, were just starting to really catch on. Some Londoners enjoyed watching, and even taking part in, their curious, quasi-military gymnastic displays. And they were the antithesis of the other great Victorian immigrant labour force, the Irish: though almost as cheap to hire, the Germans who came to London were good Protestants, famously sober, educated and respectful.

But the most agreeable thing to Britons about these poor, undersized, oppressed Germans was that they openly admired – adored! – the cousins who had so generously or conveniently found a place for them.

The Germans look up, the British look down

Everyone knew that the Good Germans longed simply to unite and to become like Britain. Their liberal politics was a direct import, stamped ‘Made in England’ for all to see, as was their progressive economics. The leading theoretical light of German liberalism was an old Etonian, John Prince Smith, who later embraced Bismarck as a Reichstag MP and who seems to have believed, in a way that put even Adam Smith to shame, that achieving universal free trade really was all that mattered in the world. Sometimes the imitation of Britain was literal and even illegal: Krupp, whose wares were later to become a byword for deadly German quality, at first tried to flog his inferior products by mendaciously labelling them ‘best English steel’.14

The greatest German novelist of the day, Gustav Freytag, a public liberal, had the hero of his Europe-wide bestseller Debit and Credit be a good man trying to become a British-style, English-speaking businessman, to the gratification of his decent boss, a man of ‘thoroughly English aspect’. Britain is the good foreign example in the book, which was a great favourit...