![]()

1

Stress: The Twentieth-Century Disease

A strange new disease has found its way into the lives of Americans and into the lives of people in other highly industrialized nations of the world. It has been steadily growing, affecting more and more people with ever more serious consequences. It is now reaching epidemic proportions, yet it is not transmitted by any known bacterium or other microorganism. The range of symptoms is so broad as to bewilder the casual observer and to send the typical physician back to the textbooks. The symptoms range from minor discomfort to death, from headache to heart attack, from indigestion to stroke, from fatigue to high blood pressure and organ failure, from dermatitis to bleeding ulcers. This disease is exacting a steadily increasing toll of human health and emotional well-being. It is not really a disease in itself but, rather, a runaway condition of a normal body physiological function, namely, stress. We now know that chronic stress causes diseases of various sorts, complicates others, and induces discomfort and misery in those who suffer from it.

Although stress as a chemical process within the body is a normal manifestation of the body’s adaptation to the demands of its environment and can be caused by physical stressors such as severe injuries or bacterial invasions, most of the chronic stress experienced by twentieth-century Americans comes from anxiety. Apprehension, conflict, crowding, upheaval in personal life, rapid and unrelenting change, and the pressures of working for a living are inducing stress in people at levels that threaten their health and well-being.

In a broad sense, this book is about human wellness—what it is, how and why we’ve been steadily losing it, and how we can get it back.

THE EXPONENTIAL CENTURY

The period from 1900 until the present stands apart from every other period in human history as a time of incredible change. Mankind, at least in the so-called “developed” countries, has lost its innocence entirely. The great defining characteristics of this period—the first three-quarters of the twentieth century—have been change, impermanence, disruption, newness and obsolescence, and a sense of acceleration in almost every perceptible aspect of American society.

Philosophers, historians, scientists, and economists have given various names to this period. Management consultant Peter F. Drucker (1968) has called it the Age of Discontinuity. Economist John Kenneth Galbraith (1977) has called it the Age of Uncertainty. Media theorist Marshall MacLuhan (1964, 1968) called it the Age of the Global Village. Writer and philosopher Alvin Toffler (1970, 1975) called it the Age of Future Shock. Virtually all thoughtful observers of America, Americans, and American society have remarked with some alarm about the accelerating pace with which our life processes and our surroundings are changing within the span of a single generation. And this phenomenon is spreading all over the industrialized world. I call this the Age of Anxiety.

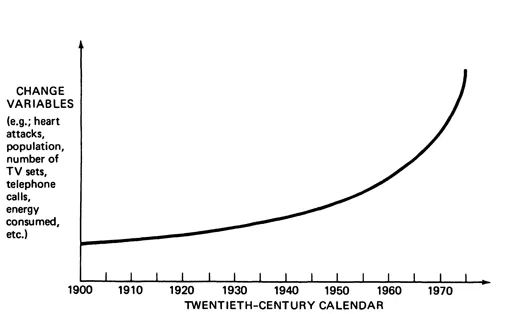

Not only are our lives changing, but most of the variables that define the change are moving at ever-increasing speeds. We not only have change, we have acceleration. A large portion of the change has occurred within recent history, largely since World War II. This suggests that the next 25 years will see even greater changes if this trend continues. The quickening pace of these change variables describes what mathematicians call an exponential curve, illustrated in Exhibit 1-1. Just looking at such a curve, showing for example the number of new inventions or processes, or the number of people in the world, or the rate at which consumer products come into being and die, gives one a feeling of apprehension. The intuitively felt questions are: “Can this continue indefinitely?” “Where are the limits?”

EXHIBIT 1-1. Many aspects of American life follow this exponential change curve.

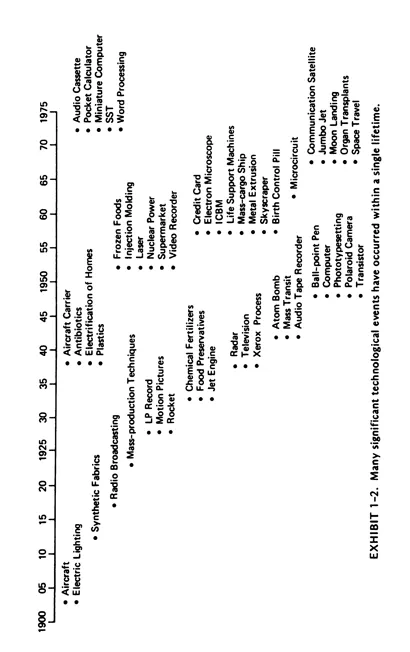

EXHIBIT 1-2. Many significant technological events have occurred within a single lifetime.

Exhibit 1-2 shows a number of selected events of the first three-quarters of the century, each of which has touched off shock waves of social, technological, and economic change throughout American society and indeed the world. With the events arrayed on a linear time scale as in Exhibit 1-2, we can grasp the awesome intensity of the change process that is underway. The more significant new arrivals include:

| Aircraft | Metal extrusion |

| Aircraft carrier | Microelectronic circuit |

| Antibiotics | Miniature computer |

| Atom bomb | Moon landing |

| Audio recording cassette | Motion pictures |

| Ball-point pen | Nuclear power |

| Birth control pill | Organ transplants |

| Chemical fertilizers | Phonograph record |

| Communication satellite | Phototypesetting |

| Computer | Plastics and other synthetic materials |

| Credit card | Polaroid photography |

| Electric light | Radar |

| Electrification of all homes | Radio broadcasting |

| Electron microscope | Rockets |

| Electronic calculator | Skyscrapers |

| Food preservatives | Space travel |

| Frozen foods | Supermarket |

| Injection molding | Supersonic transport plane |

| ICBM (Intercontinental Ballistic Missile) | Synthetic fabrics |

| Jet engine | Audio tape recorder |

| Jumbo aircraft | Television |

| Laser | Transistor |

| Life-support medical machines | Video tape recorder |

| Mass-cargo ship | Word processing machines |

| Mass-production techniques | Xerox process |

| Mass transit | |

Although these changes have had far-reaching noticeable effects, it may be that some of the most important effects have so far gone undetected. For example, we know of the fantastic power of the computer and its omnipresent influence in many areas of our lives, but you may find it a challenging mental task to list as many direct influences as possible that the advent of the computer has had on your own life. You’ll surely find the idea of the computer so intimately interwoven with many other aspects of society that it will be impossible to separate it out as a single distinct influence. Similarly, sociologists still argue about the influence on our society of television as a cultural communication mode. All agree that the impact has been enormous, but not all agree on the exact form of the impact.

We know that many of these change modes have served to put people into closer contact with one another by transferring information faster, with greater density, and with greater psychological impact. Rapid long-distance travel by jet aircraft has fostered a “mobicentric” society in which many people relocate about the country but stay in physical contact with families and friends. The airplane, as well as long-haul trucking and to some extent railroads, has made commerce a nationwide process. Goods manufactured in one corner of the country travel to all other areas for retail distribution. Multibillion-dollar food distributing corporations such as Safeway Stores, Incorporated move the products of American farms and factories about the entire country. A national telephone system puts Americans in electrical contact with one another across the continent, and indeed around the world, within seconds and at an amazingly low direct cost. Abundant electrical power for lighting keeps people active and busy much later at night than was the case in 1900.

The chronicle of these changes could go on and on. Suffice it to say that we are surrounded by change, we are imbedded in change, and change permeates virtually all of our lives as members of this exploding society. Truly, this has been so far the exponential century, and it shows no signs of stabilizing or coming to equilibrium. The disconcerting facts are that we simply do not know where we are going as a society or what will happen next. To try to predict with any confidence the developments of the last quarter of the century is a laughable exercise in fantasy which, if set down on the record, would probably prove to be ridiculously conservative when viewed from the perspective of the year 2000.

For example, take a moment to review the previous list of new events and count those that people foresaw before the beginning of the century. Only a few were even dreamed of in wildest speculation. Leonardo da Vinci and Jules Verne forecast heavier-than-air flight, but most of their contemporaries considered them hopeless visionaries. Just before Orville and Wilbur Wright demonstrated their airplane at Kitty Hawk, the U.S. Army had cut off all funds for the development, on the conviction that it was theoretically impossible.

Charles Babbage’s “calculating engine,” a contraption of gears and shafts, foreshadowed the digital computer, but no one predicted the development of the electronic technology that made it more than a curiosity. Nuclear power, television, electronics, radar, space flight, motion pictures, the Xerox process, the Bomb—all these revolutionizing changes burst into existence in a relative flash along the time scale of the twentieth century. The present-day profession of technological forecasting is more an exercise in logical possibilities, with a strong philosophical flavor, than an attempt to say what will be.

This is the nature of our world as we enter the last quarter of the twentieth century—bewildering change, ever-increasing demands on us as creatures to adapt to newness, and a growing sense of awe and apprehension about what it all means and where it all is leading us. Whether we like or not, we are all citizens of the exponential century.

THE NEW AMERICAN LIFE STYLE

Americans have become exponential creatures forced to adapt to exponential change. And, as we see later, it is taking its toll of their psychological well-being and their physical health.

One consequence of the bewildering variety of changes taking place within this exponential century has been a complete metamorphosis in the typical American life style. Most Americans living at the three-quarter mark of the twentieth century are no more like their turn-of-the-century ancestors than those ancestors were like their own ancient cave-dwelling forebears. A citizen of the 1900s suddenly transplanted into the 1970s would find himself utterly bewildered by that world. He would encounter so many things, processes, and social norms entirely beyond his imagining that he would probably remain confused and disoriented for months or even years. Similarly, a citizen of the 1970s taken back to the world of 1900 would surely find himself groping for familiar things and processes in a world that would seem incredibly primitive and decentralized.

To understand the psychological impact of the changes that have taken place within a single lifetime and to appreciate the vastly increased levels of stress that Americans now experience, we must look at the major changes in life style that have transformed 1900 man into 1970s man. Five areas of change seem to me most significant in assessing what has happened to the American creature. Although these categories may not cover all significant changes within this century, nevertheless I believe they constitute the primary reason why this period has become the age of stress.

The five significant areas of change are as follows:

-

From rural living to urban living.

-

From stationary to mobile.

-

From self-sufficient to consuming.

-

From isolated to interconnected.

-

From physically active to sedentary.

Let’s look at each of these changes in turn to see what kinds of pressures and demands for adaptation they have placed on the typical American.

In 1900 most Americans lived on farms or in rural areas. Only 40% of them lived in urban areas. However, with the rapid development of technology, transportation, and big corporations, as well as the concentration of large manufacturing operations in the cities, a steady migration brought most Americans to the cities. By 1975 almost 75% of Americans lived in urban areas. And of the remaining rural 25%, only about 4% could be classified as farmers. Many of the others made their livings by working in cities or urban areas. This has revolutionized the style of living for a large fraction of the American population, making them much less self-sufficient and much more dependent on the logistic systems that serve the cities.

The city dweller usually eats, sleeps, and lives within a few yards of other people whom he knows only casually. He is usually confined to a small plot of territory, with the necessities of life carefully condensed into living quarters and storage spaces. In some ways, the typical city apartment or condominium is reminiscent of the ancient cave. The primary difference is electricity, hot and cold water, and indoor toilet facilities. City dwellers usually spend a large fraction of their waking hours in fairly close proximity to other people, especially if they work for organizations.

A typical city worker will get up at a fixed time in the morning, drive a car to work on a crowded freeway or busy street, go into a densely populated building, ride up a crowded elevator, and work all day as a member of a social unit. He may eat lunch in a crowded restaurant and walk to and from lunch along a crowded, busy street. Living in the presence of large numbers of people induces a relatively high level of alertness in the city dweller. Everyday activities such as sprinting across the street to avoid oncoming traffic, or jamming on the brakes to avoid a scurrying pedestrian, all require the city dweller to stay alert and act quickly.

And, of course, crime and violence are frequently on the mind of the city dweller. He wonders from time to time what the chances are of being robbed, mugged, or assaulted by those who lurk insanely at the edges of the social structure, unable to meet their needs in socially acceptable ways. Larger and older cities, which some politicians like to term “our ‘mature’ cities,” generally have fairly large slum areas, which tend to breed crime and antisocial behavior as well as continued poverty. Former Mayor Lindsay is said to have listened to astronauts Borman, Lovell, and Anders describing the moon by saying, “It’s a forbidding place … gray and colorless … it shows scars of a terrific bombardment … certainly not a very inviting place to live or work,” and to have remarked that for a chilling moment he thought they were talking about New York City.

The entire setting of the city as a sociologistic operation demands a much higher level of alertness and responsiveness than the quiet, rural setting in which challenging events come much less often and with much less severity. This combination of crowding and reactivity seems to induce a much higher nominal level of stress in the city dweller than that experienced by the rural person. We can readily understand the effects of the on-your-toes orientation in keeping a person aroused for a full working day, but the effects of crowding have not been so widely recognized.

Although people vary in their tolerance and appetite for contact with other humans, every person has a comfort level that can be exceeded. Having even one person within your “near zone”—a spatial area surrounding your body out to a radius of three to five feet—will make you somewhat more aroused than simply being alone. As a creature, you react in a very basic biological way to the presence of others in your near vicinity. Prolonged close contact, without means for retreat and relaxation, can be extremely stressful for most people.

From time to time, I have noticed in myself a “crowded” feeling when I have had to drive my car on a busy Los Angeles freeway during the rush period. Sometimes, while waiting for a traffic jam to clear on the “world’s biggest parking lot,” I have looked around at the surrounding sea of cars and drivers and have begun to feel a vague sensation of imprisonment. I often watch other drivers as they hunch forward, hands gripping their steering wheels, faces fixed in expressions of intense concentration and anticipation. I watch as they “jack-rabbit” away as soon as an opening clears. Moving along at 55 miles an hour in a small steel and glass conveyance and seeing four others surrounding me at a distance of less than 10 feet away is for me a somewhat stressful experience. I believe city driving induces a low-grade level of anxiety in all drivers, although many of them have been driving for so many years they have come to see themselves as being perfectly calm. When tempers flare in very heavy traffic, the stress of driving shows through dramatically.

These two key factors, crowding and pace, induce an almost unremitting arousal within the body of the typical city dweller. This form of stress was almost completely unknown to the rural dweller of 1900, and it is to a great extent unknown even to today’s farmer or resident of a tiny out-of-the-way American town. Clearly, the migration from farms to cities was a migration from tranquillity to anxiety. Although most city dwellers seem to have learned to live in the city environment, and even to prefer it, nevertheless it has been taking its gradual toll of their health and well-being.

Second, Americans have become the most “mobicentric” people on earth. The automobile and the airplane have extended the reach of virtually all people and have cut them loose from their places of birth. Large numbers of people travel about the country on business and on vacations. They change jobs much more frequently than ever before. Some estimates hold that the typical professional person changes jobs on the average of every three to five years. Other estimates suggest that the typical family relocates to another home on the average of every six or seven years.

The typical pattern for 1900 was to be born in a community, to grow up there, to work there, to marry and raise a family there, and to grow old there. The typical late-twentieth-century style is to be born somewhere, to grow up in several different somewheres, to be educated somewhere else, to move from place to place as part of one’s career, and to get married and divorced and remarried. The American of the 1900s who could afford a vacation to Europe would have had to be quite wealthy indeed, b...