eBook - ePub

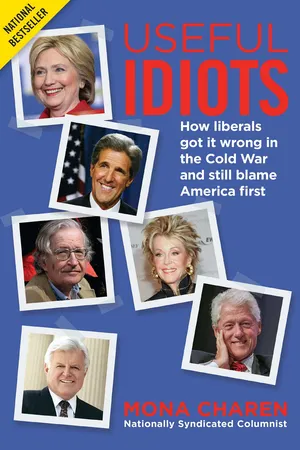

Useful Idiots

How Liberals Got It Wrong in the Cold War and Still Blame America First

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The original BESTSELLER from nationally syndicated columnist Mona Charen! Who's on the wrong side of history? The liberals who are always willing to blame America first and defend its enemies. They've tried to rewrite history, but Mona Charen won't let them as she calls out liberal hypocrisy during the Cold War and afterward; from DC elites like Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, and Jimmy Carter to Hollywood celebs like Woody Allen, Jane Fonda, and Martin Sheen to academic snobs like Noam Chomsky, Susan Sontag, and many more. Charen's devastating critique of the left's philosophical incompetence is a must-read for Americans on both sides of the aisle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Useful Idiots by Mona Charen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Biografías políticas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Brief Interlude of Unanimity on Communism

It is better to be a live jackal than a dead lion—for jackals, not men. Men who have the moral courage to fight intelligently for freedom have the best prospects of avoiding the fate of both live jackals and dead lions. Survival is not the be-all and end-all of a life worthy of man . . . . Man’s vocation should be the use of the arts of intelligence in behalf of human freedom.

—SIDNEY HOOK

IN MARCH OF 1983, PRESIDENT Ronald Reagan, speaking to the National Association of Evangelicals, used words that would resonate throughout the remainder of his presidency and beyond. Speaking of the “arms race,” he said, “I urge you to beware the temptation of pride—the temptation blithely to declare yourselves above it all and label both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong, good and evil.”1

The use of the term “evil empire” provoked a fusillade of contempt from the American liberal Left. Many news reports characterized Reagan’s language as “strident” (or found observers who would). The Associated Press quoted Lord Carrington, former British foreign secretary, as condemning “megaphone diplomacy,” and calling for “dialogue, openness, sanity, and a nonideological approach to the dangerous business of international affairs.”2

Henry Steele Commager, then a professor of history at Amherst, was quoted in the Washington Post a few days later, identified only as a “distinguished historian,” not as what he was: a well-known liberal intellectual. He condemned Reagan’s speech as “the worst presidential speech in American history, and I’ve read them all. No other presidential speech has ever so flagrantly allied the government with religion. It was a gross appeal to religious prejudice.”3

Time magazine’s Strobe Talbott, who would later serve as deputy secretary of state in the Clinton administration, made his disapproval clear. “When a chief of state talks that way, he roils Soviet insecurities.”4

Hendrik Hertzberg, a former speechwriter for President Carter and later the editor of the New Republic magazine, was beside himself. “Reagan’s speeches are much more ideological and attacking than any recent president’s speeches,” he told the Washington Post. “Something like the speech to the evangelicals is not presidential; it’s not something a president should say. If the Russians are infinitely evil and we are infinitely good, then the logical first step is a nuclear first strike. Words like that frighten the American public and antagonize the Soviets. What good is that?”5

The notion that that harsh criticism of the Soviet Union had to be stifled because it would lead to nuclear war was rarely stated as bluntly as Hertzberg did, but it was widely believed on the Left, and resulted in a tendency—evident until the day the Soviet Union closed its doors forever—to excuse, airbrush, and distort the aggressive and despicable acts of that regime.

Mary McGrory, a columnist for the Washington Post, never quite got over her amazement at Reagan’s obtuseness. Months later, writing on a related matter, she noted that “The president . . . embarrasses them [members of Congress] with his talk of the Soviets as the ‘evil empire,’ but they think he has convinced the country that the communists are worse than the weapons.”6

It was obvious to liberals that the exact reverse was the case. It made some observers almost panicky to think that Reagan actually believed what he said. George W. Ball had been undersecretary of state in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. He, too, referred to the “evil empire” speech as proof that Reagan was dangerous and simplistic on foreign policy. Writing of events in the Middle East, he condemned Reagan for “obsessive detestation of what you call the ‘evil empire.’ . . . Mr. President, you have set us on a dark and ominous course. For God’s sake, let us refix our compass before it is too late.”7

“Primitive, that is the only word for it,” fumed Anthony Lewis, of the New York Times. “Believers, Mr. Reagan said, should avoid ‘the temptation of pride’—calling both sides at fault in the arms race instead of putting the blame where it belonged: on the Russians. But there again he applied a black and white standard to something that is much more complex. One may regard the Soviet system as a vicious tyranny and still understand that it has not been solely responsible for the nuclear arms race. The terrible irony of that race is that the United States has led the way on virtually every major new development over the last thirty years, only to find itself met by the Soviet Union.”8

Of course, even if Reagan had said that the Soviet Union was “infinitely evil,” and we, “infinitely good,” as Hertzberg recalled the speech (Reagan had not said that), it hardly follows logically that the “next step” would be a nuclear first strike. Hertzberg is a Harvard educated editor and certainly capable of understanding this, but fear distorted liberal thinking.

Sovietologist Seweryn Bialer of Columbia University disapproved of Reagan’s rhetoric. Yet he provided evidence that it had hit home among the aged bosses of the Kremlin:

President Reagan’s rhetoric has badly shaken the self-esteem and patriotic pride of the Soviet political elites. The administration’s self-righteous moralistic tone, its reduction of Soviet achievements to crimes by international outlaws from an “evil empire”—such language stunned and humiliated the Soviet leaders . . . [who] believe that President Reagan is determined to deny the Soviet Union nothing less than its legitimacy and status as a global power . . . status . . . they thought had been conceded once and for all by Reagan’s predecessors.9

In retrospect, it is clear that denying legitimacy to the Soviet Union was a stroke of brilliance—a moral challenge that resonated from Berlin to Vladivostok. The Soviet Union did not deserve legitimacy. But at the time it was heresy. In 1983, Communism was regarded by everyone to the left of center in American politics as either a fact of life to be accepted or a genuine humanitarian impulse that had, perhaps, gone a little too far. Reagan’s rhetoric profoundly disturbed the status quo because it made the moral case for anticommunism, whereas the conventional wisdom held that the “mature” and “realistic” approach to Communism was accommodation, not confrontation. Liberals thought they had convinced everyone who mattered that anticommunism was the thing to be feared, not Communism itself. And then along came Reagan suggesting that the Cold War was really a matter of good versus evil. Liberals who sought to deny the moral dimension of the conflict were blindsided by Reagan’s assertive anticommunism and responded with calumny and contempt.

By 1983, Communism ranked far below many other evils most liberals could name. Communism was certainly not worse than nuclear war—and this conviction would form the scaffolding of many a liberal position, from opposition to the MX missile to support for the nuclear freeze and unilateral disarmament. Fear of nuclear war would also form the unstated subtext of many liberal responses to Cold War challenges in other realms as well. The desire to soft-pedal criticism of the USSR or China, for example, sprang in part from secret sympathy with the collectivist states, but also from fear of provoking them to anger.

Communism was not nearly as evil, most liberals believed, as the false charge of being a Communist. And, though they would probably never admit this openly, the clear implication of liberal/left-wing solidarity behind Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Alger Hiss was that it was more distasteful to make a true charge of communism than actually to be a secret Communist. In Anthony Lewis’s fulmination against Reagan’s evil empire speech, he paused over Reagan’s kind words for Whittaker Chambers, noting with incredulity that “he cites Whittaker Chambers as a moral arbiter!”

It was not always this way.

THE ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR

When the Bolsheviks hijacked the Russian Revolution in 1917, most Americans responded with dismay. It was understood that while the Russian Revolution had been a mass uprising with multifarious leadership, the Bolsheviks were thugs who used force to silence and eliminate the more democratic elements in the coalition of which they were a part.

But by the 1930s, when the U.S. and other industrialized nations were enduring the Great Depression—a crisis that many believed marked the “death throes” of capitalism—sympathy for Communism and Soviet Russia expanded markedly. Leftist writers like Beatrice and Sydney Webb and New York Times reporter Walter Duranty offered rosy assessments of Communism under Lenin and Stalin. (Years later, it was revealed that Duranty was actually being blackmailed by the Soviets throughout his stint in Moscow.) Journalist and Lenin admirer Lincoln Steffens famously pronounced in 1921, “I have seen the future and it works.”10

Membership in the Communist Party USA reached its peak in 1939, at 66,000 registered members.11 William Z. Foster, the Communist candidate for president in 1932 earned 102,785 votes.12 But just when Communism was enjoying its golden age in America, word of Stalin’s purges began to filter out of the Soviet Union. Thousands of loyal Communists, many of whom had performed leading roles in the October Revolution, were paraded before rigged tribunals. The most prominent victims went through the degrading spectacle of “confessing” to a list of errors and crimes against the state. The prisoners were assured that their own lives, or those of their families, would be spared if they confessed to these trumped up charges. Stalin pocketed the confessions—and then had them shot anyway.

Along with the purge trials came word of widespread repression and slaughter dwarfing anything visited upon the Russians by the tsars. Knowledge of the terror-famine, which took the lives of some ten million people, did not become widespread until many years later (in part due to Walter Duranty’s dishonest reporting). In 1939, when Stalin signed a nonaggression pact with Hitler, carving up Poland and giving Hitler a free hand to attack the West, most Americans became firm anticommunists.

By the early years following World War II, a rough consensus had jelled about what was then unselfconsciously labeled the “communist threat.” Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives alike believed that the United States must resist the expansion of Communist tyranny. Though many on the left continued to make excuses for Stalin—notably Lillian Hellman, Owen Lattimore, Corliss Lamont, and I. F. Stone—the lesson of the century, mainstream policymakers agreed, had been Munich. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s naive 1938 pronouncement after meeting Hitler that he had achieved “peace in our time” was viewed, in light of the terrible war that followed, as the most foolish and indeed cowardly act of diplomacy imaginable. In the postwar period, leading Americans were certain that appeasement of an aggressor was foolish and immoral and they were determined to avoid that mistake with the Communists.

Though the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had been wartime allies against Hitler, America had not forgotten the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, which had made World War II possible. (When Ribbentrop traveled to Moscow to negotiate the deal, he reported feeling as comfortable with the Communists “as among my old Nazi friends.”)13 Nor did the conduct of the Communist Party USA and its fellow travelers evoke sympathy. Fully in lockstep with Kremlin policy, the American Communists had faithfully pushed the antifascist line until the Hitler-Stalin Pact. They then pivoted 180 degrees to denounce Britain’s “imperialist war” only to turn about again after Hitler invaded the USSR in 1941. They were not a true American party, but marionettes, dancing to a tune called in Moscow.

During the Soviet occupation of Poland, 15,000 Polish officers surrendered to the Russians. Their fate was the subject of considerable dispute for forty years. In 1943, 4,400 officers, found with their hands tied with wire behind their backs and bullets in the backs of their heads, were discovered by the Nazis at Katyn Forest. The Soviets denied the massacre and blamed the Nazis (who were certainly capable of the atrocity).

With time, the Soviets’ lie was uncovered. In 1990, just before the fall of the Soviet Union, two more mass graves of Polish officers were found, bringing the death toll to more than 15,000. When the Soviet archives were opened fifty years after the massacre, a document ordering the executions was found. It contained the signatures of every member of the Politburo.14

In 1941, the Nazis surprised the Soviets by turning on them and invading Russia. The peoples of Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, and other Soviet captive nations at first welcomed the Germans as liberators. But the savagery of the Nazis soon persuaded them that it was better to stick with the devil they knew. Later when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and brought America into the war, the U.S. and the USSR became temporary allies.

While the U.S. under FDR’s leadership took this alliance to heart, warming to “Uncle Joe” Stalin and condemning anticommunist sentiments as unpatriotic, Stalin took a different view. Even before the war’s conclusion, the Soviet Union had activated a huge network of spies among its allies, principally the U.S. and Great Britain, in preparation for the time when they would revert to being enemies.

After the war, Stalin invited the free Polish government in exile, whose members had been patiently awaiting the war’s end in London, to visit Moscow. When they arrived, they were arrested. At Yalta, Stalin had promised Roosevelt and Churchill that Poland would have free elections. But at war’s end, he rigged the election to ensure a Communist victory. Roosevelt went to Warm Springs, where he died in April 1945, surprised that his famous charm had failed to work on Uncle Joe.

Truman entered the presidency naive and somewhat ignorant. He had absorbed the soft Roosevelt administration view of the Soviets. Confiding in a Missouri friend toward the end of the war, Truman said, “You are needlessly worried about Russian communism. I am worried about British imperialism.”15 But he was a quick study and soon took the measure of Stalin, coming to a more realistic view of him than his predecessor had.

Soviet troops were dispersed throughout Eastern Europe. Unlike the Americans, who rapidly demobilized as soon as hostilities ceased, the Soviet troops remained in order to install friendly governments throughout the region. Reports reached the West of mass arrests and liquidations. One such was the Swede Raoul Wallenberg, a saint of the war years. He had left a comfortable life with a banking family in Stockholm to risk everything to save Jews, and succeeded in saving the lives of thousands. (It was he, not Oscar Schindler, who deserved a major movie about ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Introduction: None Dare Call It Victory

- Chapter One: The Brief Interlude of Unanimity on Communism

- Chapter Two: The Consensus Unravels

- Chapter Three: The Bloodbath

- Chapter Four: The Mother of All Communists: American Liberals and Soviet Russia

- Chapter Five: Fear and Trembling

- Chapter Six: Each New Communist is Different

- Chapter Seven: Post-Communist Blues

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright