![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Beginning of Our Voyage and the Properties of Data

“It has been said that data collection is like garbage collection: before you collect it you should have in mind what you are going to do with it.”

—Russell Fox, Max Gorbuny, and Robert Hooke in The Science of Science

If I had to pinpoint the moment when the idea for this book struck me, it was while walking the convention floor at the 2011 International CES in Las Vegas. After any show, tech writers love debating the best new products and technologies. At the 2011 CES they had plenty to choose from. Over four short days, a plethora of new technologies and innovations had been launched. Ford introduced its first all-electric car and Verizon unveiled its 4G LTE network. Samsung showed off its newest SmartTV technologies, and MakerBot displayed some of the earliest 3D printers. We saw the introduction of a profusion of tablet computers laying the groundwork for 2011 to fast become the year of the tablet. There were first-generation PC ultrabooks, extremely lightweight but powerful laptops, and Microsoft’s Xbox Kinect had just entered the market on its way to becoming the fastest-selling consumer electronics device on record, according to Guinness World Records.

It wasn’t any particular product or technology that turned on the proverbial light bulb for me back in 2011. It was all the technologies and devices at CES coming together. I was reminded of futurist writer Arthur C. Clarke, who is perhaps best known for the third law in his 1961 book Profiles of the Future, which states: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”1 As I looked around the halls of CES, I saw magic. I had the immediate realization that a trend once novel and groundbreaking was suddenly quite ordinary and unremarkable—and that made it all the more remarkable.

The digital conversion, underway for more than a decade, was nearly complete. There were few analog products on display. What had been revolutionary in the 1990s, when CES was the birthplace of the first digital cameras and digital televisions, had now become commonplace. And these digital products were now colliding at an increasing rate—creating entirely new devices and services. It’s not that this thought hadn’t occurred to me before. My job is to watch technology trends and interpret their implications. And I had had plenty of pithy, brilliant things to say about the tablet PC craze or the revolutionary 4G network. I could pontificate all day on the economic impacts of mobile devices or the future of television. Taken individually, these products and technologies are each special and deserving of economic study. And that’s what usually happens when you find yourself in the middle of a civilization-altering moment: you take things individually. It’s the future historians who are supposed to connect the dots, find the paradigm-shifting trends, and explain what it all meant. It’s much harder to do that in the present, and explain what all of these things add up to.

Overcome by this rather simple observation—that the world had gone completely digital—I asked myself the question that led to the book you are reading: What does it mean for us—for human beings—when everything is digital? Is it just a curious trend, like a fashion, changing the way things look, but having little real impact on how we live? Certainly it is more than that. Could it be like the invention of the telephone or the television—game-changing products that forever altered the way human beings receive and provide information? We’re getting close, but those are only two products. Of course their impact was revolutionary, but also isolated: you could step away from the television or hang up the phone.

My thinking was still too narrow. Remember, I told myself, everything will be digital, not just a few products. So, really, we’re talking about something on a larger scale . . . something like the advent of electricity . . . ah-ha! I finally felt like I was getting to the essence of the change before us. My simple question had begun to open horizons I hadn’t considered. The truly immense scope of digital began to unfold. Digital technology wasn’t only going to change what we did and how we did it. It was evolving in a way that would completely transform how cultures are structured and redefine societal norms.

When Thomas Edison invented the world’s first light bulb, it was an extraordinary moment. But we’re talking about just a single light bulb. How would that change civilization? Were people’s homes suddenly wired? Did power stations just spring up over night? Could anyone have had any realistic notion that one day everything would be electric? Indeed, as my CEO Gary Shapiro noted in his best-selling book Ninja Innovation: The Ten Killer Strategies of the World’s Most Successful Businesses, Edison’s true revolutionary innovation was the Pearl Street power station in Manhattan, which provided the current needed to power the light bulbs: “The reason the Pearl Street station was so important—and why Edison would have failed had he not created it—is that the electric light bulb couldn’t replace the gas lamp as the primary source of lighting until the entire electrical system was created to sustain it. Otherwise, Edison would have been just the guy who had created a cool, but useless, gadget. In other words, inventing the light bulb was not the end for Edison; it was only the beginning.”2

The first truly digital consumer product—the CD player—debuted at CES in 1981. It was a big moment, but it did not mark the beginning of the Digital Age. One product cannot do that. Computers go back fifty years. But only a select few of us had one in our homes before the 1980s. Even in the early 80s there wasn’t much of a home market for computers, aside from a few niche devices that functioned more as large gaming systems. It was not until Apple brought to market one of the first truly consumer-friendly, cost-efficient Macintoshes in 1984 that personal computers became a mass market. That marked a paradigm shift; that’s the story everyone remembers; that’s why Steve Jobs would have earned a place in human history had he done nothing else. It was not the invention of the computer; it was the computer’s adoption by the masses.

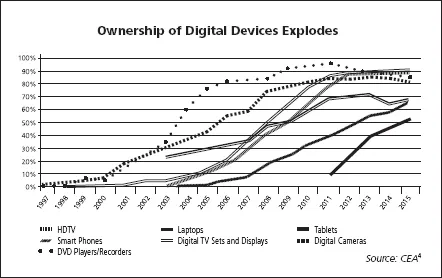

Twenty years ago, no one owned a smartphone and only the richest few had a mobile device. Today, smartphone penetration is roughly 70 percent in the United States, and people check their devices 150 times a day. The invention itself didn’t immediately lead to the end of the phone booth. The era of the phone booth ended only when, decades later, everyone had a cell phone.

Let’s go back even further. Quick: Who invented the automobile? It’s perhaps one of the most important inventions in human history, yet most don’t know who is actually credited with inventing it. German engineer Karl Benz (as in Mercedes-Benz) is generally regarded as the inventor of the first automobile powered by an internal combustion engine. That was in 1886. Who owned a car in 1886? Or 1896? Or 1906? Almost no one.

You could be forgiven for thinking Henry Ford invented the automobile. He might as well have. It was Ford, not Benz, who brought the automobile to the masses. Before Ford, the car was just a luxurious alternative to the horse and buggy. After Ford, the car was a necessity. As every school child knows, it was Ford’s revolutionary manufacturing techniques that made the automobile a mass market product. In 1909, its first year of production, a Ford Model T cost $850 (nearly $23,000 in today’s dollars). By the 1920s, its price had dropped to $250 (about $3,000 in today’s dollars) and with its affordability improving dramatically, adoption went up drastically. In November 1929, Popular Science Monthly reported, “Of the 32,028,500 automobiles in use in the world, 28,551,500, or more than ninety percent, it is stated, were produced by American manufacturers. . . . There is, according to these figures, one automobile for every sixty-one persons in the world, an average accounted for by the high ratio in the United States of one automobile for every 4.87 persons.”3

The automobile age didn’t begin when Benz fired up the first car in 1886. It began in 1914 when a Ford assembly-line worker could afford the very product he was making on just four months’ salary.

It goes without saying that without Benz, Ford might not have made his first Model T, and had Edison not invented the first light bulb, he would have had no reason to build the Pearl Street power station. Rather, my point is that the existence of a product—its creation—does not transform the world. It’s only when that product or technology reaches a critical mass of users or adopters that the human experience changes and a new age is born. Indeed there are countless ingenious inventions that might have fundamentally altered our way of life, but for whatever reason failed to reach a mass market. Either they disappeared or they evolved into something that could reach a mass market.

In short, economics plays as large a role in the progression of human technology as design, engineering, and mathematics. In many cases, it is the dominant role. I can’t tell you how many products I’ve marveled at on the show floor of the International CES that their makers, industry insiders, and critics were sure was The Next Big Thing. Maybe they were right; maybe it would have been. But until it’s in the hands of the middle class family of four with two working parents, it’s just a novelty.

Digitization of data and devices is today at that inflection point. Digital devices are broadly accessible and becoming increasingly widely adopted. Digital’s impact on the world will be more consequential than even the impact of electricity. I recognize that is a bold declaration. In the next chapter we’ll explore in greater depth the reasons that the impact of our transition to digital will be so pronounced and significant. For now, let me offer some general observations.

1. Unlike other technologies, including electricity and analog devices, digital technology is subject to Moore’s Law. Named after Gordon Moore, whose 1965 paper in Electronics Magazine explained the phenomenon, Moore’s Law states that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles every two years. This leads to two major results: first, processing power continually increases and thus technological innovations continually occur; second, digital devices become very cheap very quickly.

2. Digital devices and technologies have far exceeded the ownership rates of a wide range of things—from the automobile to many major appliances. A quick look at a few select products tells the story: mobile phones, DVD players, digital televisions, computers, and digital cameras have all achieved an 80 percent penetration rate in the United States:

3. Digital products have found their way into nearly every corner of human society. Much of this book is devoted to exploring both the well-known corners and the ones most of us never imagine. However, digitization will go far beyond what we can see today. Electrical applications start and end with “what needs power,” but digital devices start and end with data—and data, we are about to learn, is infinite.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DATA

To understand digital technology’s near-limitless potential we first need to understand its primary function: in its most basic form, digital is simply zeros and ones. But these zeros and ones come together to inform a myriad of things. Digital’s ability to process and transfer enormous amounts of data—and I’m referring to amounts that simply dwarf anything that came before it—is what sets it apart from nearly every other human technology. Nothing comes close.

By and large human technology has followed a mechanical progression. First, we invented the wheel, then we made tools, then machines. The Industrial Revolution after all was a revolution in mechanical engineering, first in agriculture, then in manufacturing. We found ways to build better mousetraps. But that progress basically left data untouched.

Indeed, throughout the entire course of human history, revolutions in data transmission and reception have been exceedingly rare. So rare, in fact, that we can recount a brief his...