- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

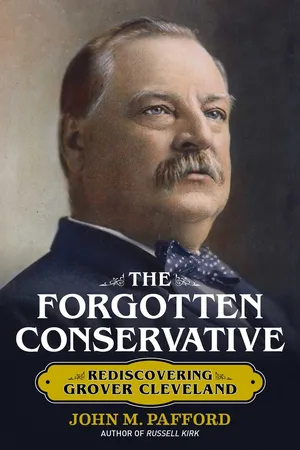

Grover Cleveland is truly the forgotten conservative: a man of dignity, integrity, and courage often overlooked by the history books. Historian and author John Pafford reveals a president who deserves more attention. Cleveland might not have presided over deeply troubled times, but he set a standard for principled leadership in office that is especially relevant today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

BEGINNINGS

STEPHEN GROVER CLEVELAND WAS born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey, the son of Richard F. Cleveland, a Presbyterian pastor, and Ann Neal Cleveland, the daughter of a Baltimore law book publisher. Named after a clergyman his father had admired and succeeded, he was the fifth of nine children. When he was nineteen, he started signing his name “S. Grover Cleveland”; about two years later, he dropped the initial.

Richard Cleveland had graduated from Yale with honors in 1824 and then moved on to Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1828, he was ordained, married Ann Neal, and moved to Windham, Connecticut, where he served as pastor of the First Congregational Church. Problems with his health provoked a move in 1832 to the milder climate of Portsmouth, Virginia. His health had improved by 1834, and he accepted a call from the Presbyterian Church in Caldwell. A kindly, studious man who was neither a brilliant intellectual nor a great preacher, Richard Cleveland struggled to support his large brood, but he reared them faithfully on the Bible and the Westminster Confession. Integrity and hard work were expected in this stern yet loving Calvinistic household, and Grover’s Christian faith became deeply rooted. Years later, shortly before his death, he would write: “I have always felt that my training as a minister’s son has been more valuable to me as a strengthening influence and as an incentive to be useful than any other incident of my life.”1

The family moved to Fayetteville, New York, in 1841, and later to Clinton and Holland Patent, all in the central part of the state. During his boyhood years in these communities, Cleveland grew into a hearty, fun-loving young man with a strong constitution and an equally strong sense of responsibility. As a student at Fayetteville Academy and Clinton Liberal Institute, he showed himself a diligent, solid student and looked forward to attending nearby Hamilton College. In 1853, though, his father, who had been in declining health for several years, died. It now was necessary for the sixteen-year-old Grover to set aside his college plans and work to support his mother and the four siblings still at home. Although his formal schooling had ended, nineteenth-century academic standards ensured that Cleveland was well educated. For example, though not an exceptional student, he had studied Latin, working on translating Virgil’s Aeneid. The caliber of his adult writings and speeches would be creditable for a college graduate today.

Cleveland first worked as a bookkeeper and assistant teacher in the literary department at the New York Institute for the Blind in New York City, a position suggested to him by his older brother William, who had gone to Hamilton College and had taught at the institute himself. The state-supported school taught children from poor families, and the conditions were grim. The living quarters were cold, the food was poor, and the children suffered from a lack of love and attention. Cleveland left after a year and never looked back fondly on his time at the institute. He did, however, begin a life-long friendship with another teacher, Fanny Crosby, the blind hymnist who composed such evangelical standards as “To God Be the Glory,” “Blessed Assurance,” and “All the Way My Savior Leads Me.” Cleveland, still in his teens, impressed her with his maturity, hard work, kindness, and determination to improve himself.

Cleveland first returned to Holland Patent. Unable to find a job there, he decided to move on to Cleveland, Ohio, a city whose name seemed to call him.2 On the way, he stopped in Buffalo to visit an uncle, Lewis Allen, a prosperous cattle breeder with a farm at Black Rock, just outside the city.

Cleveland’s decision to stop in Buffalo proved providential. The city, says H. Paul Jeffers, was a perfect match for the young man:

Bustling, uncouth, materialistic, hardworking Buffalo stood on the cusp of the rugged Western frontier and the conservative, refined East. It offered little in the way of surface graces but brimmed with people of common sense, tenacity, and stubborn character. These traits harmonized with Grover Cleveland’s spirit of independence, conscientiousness, efficiency, and, above all, honesty....3

Situated on the shores of Lake Erie and the second-largest city in New York, Buffalo was still rough around the edges—not much in the way of museums and classical music, but plenty of bars and brothels. It was developing, though, with churches and impressive homes going up. The Erie Canal, which opened in 1825, was the key to the city’s prosperity. Running from Buffalo to Albany, it connected the Great Lakes with New York City and the Atlantic Ocean. This water route flourished until later in the century, when the growing railroad network superseded it.

Lewis Allen urged his nephew to stay in Buffalo and found him employment with the law firm Rogers, Bowen & Rogers. Beginning in December 1855, Cleveland performed routine tasks like copying documents while studying in the firm’s law library and learning from its attorneys in preparation for the bar examination. His diligence and intelligence impressed his employers. In 1859, he earned his license to practice law. Cleveland remained with the firm until 1862, when he was appointed to his first public office, assistant district attorney for Erie County, a post in which he served for three years. He distinguished himself with his integrity, hard work, mastery of his cases, and his ability to argue persuasively before judge and jury. This was a young man with a promising future.

Cleveland was still too young to vote in the presidential election of 1856, but he supported James Buchanan, considering John Fremont, the first Republican nominee, too flamboyant. His political sympathies were a source of tension between himself and Lewis Allen, an early and ardent Republican, for whom Cleveland retained affection and appreciation in spite of their partisan differences. The young man was influenced by the memory of his father’s distaste for the radicalism of many abolitionists, and his employers and professional associates favored the Democratic Party. Most important, Cleveland’s conservative beliefs and temperament were more at home in the Democratic Party of that time.

The new Republican Party opposed slavery in principle, campaigning for “Free Speech, Free Press, Free Soil, Free Men, Fremont and Victory.” Although their abolitionist principles were clear, the Republicans focused on simply preventing the extension of slavery. The party’s first presidential nominee, John Charles Fremont, had attracted the attention of the country as a dashing, adventurous explorer of the West, as an army officer in the war with Mexico, and as a U.S. senator from the new state of California.

The Democrats alleged that a Republican victory in the national election would cause the South to secede and engulf the country in civil war. The Democratic Party straddled the issue of slavery, keeping both anti-slavery and pro-slavery elements within the fold. The party’s 1856 presidential nomination went to James Buchanan, who had served in both houses of Congress, represented the United States in Russia and in Great Britain, and had been secretary of state during the Polk administration.

Complicating the election that year was the American Party—the so-called “Know-Nothings”4—which took a strongly nativistic stance, opposing immigration and Roman Catholicism. The Know-Nothings favored a requirement that holders of public office must be born in the United States and included a prohibition on office-holding by Roman Catholics. The party avoided the issue of slavery in its platform and nominated former president Millard Fillmore.

Victory in the November election went to Buchanan thanks primarily to the solid South. With 45 percent of the popular vote, he carried nineteen states (fourteen of them in the South) with 174 electoral votes. Fremont was the choice of 33 percent of the voters and carried eleven states with 114 electoral votes. Although Fillmore received only the eight electoral votes of Maryland, he was one of the most successful third-party candidates in U.S. history, winning 22 percent of the popular vote. As the national conflict over slavery deepened, the American Party ceased to be relevant. Its anti-slavery members moved into the Republican Party, and those who favored slavery supported the Democratic Party in the South and then secession from the United States.

dp n="23" folio="6" ?In 1860, Cleveland voted for Stephen A. Douglas, the presidential candidate of the northern Democrats. The victory of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican president, led to the secession of eleven southern states. Although not enthusiastic about the war that began in the spring of 1861, Cleveland was firmly anti-slavery, and he supported the administration’s effort to defeat the South and restore national unity.

The Enrollment Act of 1863—the Civil War draft—permitted men to avoid conscription by supplying a substitute. One of Cleveland’s brothers was a clergyman making little money, and two others were in the army, so his income was needed to support his mother and two sisters. This was the very hardship that the policy of substitution was intended to alleviate, and Cleveland took advantage of the exemption from military service by hiring a substitute.

It is not indisputably clear, but it is likely that the Democrats’ support of a negotiated settlement that would leave the South independent led Cleveland to vote for Lincoln’s reelection in 1864. The Democratic platform called for “peace without victory.”5 It also criticized the Lincoln administration for enlisting blacks in the army. The party made a gesture for unity by nominating General George McClellan for president and Representative George Pendleton of Ohio for vice president. McClellan had broken with Lincoln over the conduct of the war (Lincoln considered him too dilatory), but he did favor winning the war, one of a minority of Democrats who supported that stance. Pendleton stood with the majority of Democrats who wanted to end the bloodshed even if that meant the loss of the South.

As the Democrats adjourned their national convention in August 1864, their prospects for victory in November appeared bright, and Lincoln feared the worst. Although the blockade of southern ports was strangling the Confederacy and the Union’s control of the Mississippi had cut the South in two, it nevertheless appeared to many voters in the summer of 1864 that the war had stagnated. In Virginia, Ulysses S. Grant’s army could not crush the Confederates under Robert E. Lee, and casualties were mounting rapidly. William Tecumseh Sherman’s invasion of northern Georgia was being parried skillfully by Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, who inflicted heavy losses on the invaders. But the tide eventually turned, just in time for Lincoln’s electoral fortunes. On August 5, Admiral David Farragut seized the Mobile Confederates’ last major port on the Gulf of Mexico, and on September 8, Sherman’s army occupied Atlanta. McClellan received a mere 45 percent of the popular vote in November, carrying only New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky. The war would end before the middle of the following year.

Cleveland was the Democratic nominee for Erie County district attorney in 1865. He lost a close race in the Republican county and returned to his law practice, which prospered as his reputation for integrity and ability spread. In 1869, he entered into a partnership with Albert P. Laning and Oscar Folsom, the father of his future wife.

In 1870, Cleveland accepted the Democratic Party nomination for Erie County sheriff and won the general election. The position offered plenty of free time during which he continued his studies, making up for his limited formal education. During his three-year term, Cleveland had to hang two convicted murderers. He did not oppose capital punishment, but he found the duty of execution unpleasant. By the end of his term, Cleveland’s reputation for honesty, ability, and strength had grown. Content with the experience gained, he declined to run for reelection, recognizing, in all likelihood, that the opportunities for growth and advancement in a second term were limited. Once again he returned to private practice.

dp n="25" folio="8" ?Cleveland did not see the legal profession simply as a way to earn a living but rather as a calling. He certainly had no objection to prosperity, but his sense of justice was preeminent. He would not accept a client unless he believed him to be in the right. In time his reputation for ability, honesty, and hard work made him one of the most successful lawyers in Buffalo.

Cleveland’s capacity for work was impressive. After a full day in the office, he could work through the night, take a bath, drink some coffee, and be back in the office at eight o’clock the next morning. Still, the jovial, fun-loving bachelor could play as hard as he worked, and he enjoyed the social life of Buffalo’s beer halls. With one important exception, however, women seem not to have figured in his social life.

That exception was Maria Halpin, an attractive, educated widow of thirty-three who moved to Buffalo from Jersey City in 1871. She worked as a clerk and then as the manager of the cloak department at Flint and Kent, a department store. She was involved with a number of men, including Cleveland. In 1874, Maria gave birth to a son and claimed that Grover Cleveland was the father. Curiously, she named the infant Oscar Folsom Cleveland. Cleveland’s law partner had a notoriously wandering eye, but he was married, as were other men with whom Maria had been involved. Considering the number of men in her life, a definitive identification of her child’s father was impossible. Cleveland, a financially successful bachelor, was an attractive target. It is clear that Cleveland had an affair with Maria. The judgment of historians about his paternity of her child usually reflects their favorable or unfavorable opinion of him in general. The truth about the paternity of Maria Halpin’s child probably will never be ascertained.

Perhaps to protect his partner Folsom, Cleveland agreed to provide for the child. He soon learned that Maria was drinking heavily and not caring for the baby, so he took steps to have her admitted temporarily to an asylum and the boy placed in an orphanage at Cleveland’s expense. The child was eventually adopted by a prominent family in western New York and grew up to be a doctor. After her release, Maria married and settled in New Rochelle, New York. If Cleveland believed that the affair was now behind him, however, he was mistaken.

In 1875, Oscar Folsom was killed in a carriage accident. He left his wife and one daughter well provided for financially. The girl, eleven years old, had been named “Frank” after an uncle. Understandably, she later adopted the more feminine “Frances.” Acting as the young girl’s guardian, Cleveland took an avuncular interest in her (she called him “Uncle Cleve”) until she grew up, whereupon his interest developed in another direction.

In the meantime, Cleveland’s law practice continued to flourish, setting the stage for his extraordinary political career. Although he was active in the local Democratic Party, he had betrayed no ambitions beyond obtaining a judgeship. But in 1881, the corruption and ineptitude of Buffalo’s municipal government sent Democratic leaders in search of a strong, honest candidate for mayor who could attract broad support. Corruption was prevalent in both parties. Recent mayors, both Republican and Democratic, had been personally honest but incompetent and weak. Some men from both parties had considered forming a third party, committed to clean, efficient government. Democrats, detecting the opportunity to capitalize on this widespread disgust, approached Grover Cleveland, a man who could attract votes across party lines. At the same time, there were important Democrats who were content with the status quo. They believed the reformers were weak and ineffective. If Cleveland were the nominee for mayor, they calculated, he would lose, and the cause of reform would be dead. This proved to be a serious miscalculation.

The Democrats nominated Cleveland, and he was elected in November with the support of reform-minded Republicans who were unhappy with their party’s nominee. Cleveland’s reputation for honesty, courage, and knowledge of the law made him the logical choice for all who wanted Buffalo to be a better place to work and raise their families.

Soon after he took office on January 1, 1882, an enormous sewer and water project gave Cleveland the opportunity to demonstrate not only that he was honest, but also that he had the courage and fortitude to vanquish corruption. The new mayor blocked a bid that involved kickbacks to aldermen. Pressure from the press and the public forced the aldermen to reverse themselves and accept a lower bid from an honest firm.

Cleveland’s vigorous exercise of the veto eliminated taxpayer funding of projects that might have been praiseworthy but that he considered beyond the legitimate bounds of government action. He objected, for example, to giving municipal funds to the Firemen’s Benevolent Association, and to the Grand Army of the Republic (a Civil War Union veterans’ organization) for celebrating the Fourth of July. This type of reform activity spread through the municipal government and attracted the attention of those scouting talent for a larger stage.

The governor of New York was the Republican Alonzo B. Cornell. Chester Alan Arthur, who had succeeded to the presidency after the assassination of James Garfield, sought tighter control over his home state in preparation for his own run for the White House and pressed his secretary of the Treasury, Charles J. Folger, to challenge Cornell for the 1882 Republican gubernatorial nomination. Folger won, but he alienated Republican reformers, who resented President Arthur’s ties to Senator Roscoe Conkling’s political machine.

On the Democratic side, the leading candidates were Roswell P. Flowers, a wealthy former U.S. Representative and the upstate favorite, and Henry W. Slocum, a Civil War general and the choice of the New York City party. Samuel Tilden, the former governor and Democratic nominee for p...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 - BEGINNINGS

- CHAPTER 2 - GOVERNOR

- CHAPTER 3 - TO THE WHITE HOUSE

- CHAPTER 4 - THE FIRST TERM

- CHAPTER 5 - DEFEAT AND INTERREGNUM

- CHAPTER 6 - BACK INTO THE ARENA

- CHAPTER 7 - SECOND TERM

- CHAPTER 8 - TRANSITION

- CHAPTER 9 - TWILIGHT

- EPILOGUE

- AFTERWORD

- APPENDIX - THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE EXECUTIVE

- Acknowledgments

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Forgotten Conservative by John M. Pafford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.