eBook - ePub

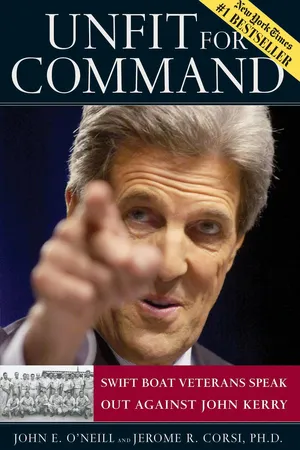

Unfit For Command

Swift Boat Veterans Speak Out Against John Kerry

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"What sort of combination of hypocrite and paradox is John Kerry?" asks this heated critique of the Democratic presidential candidate's Vietnam–era military service and antiwar activism. O'Neill, a lawyer and swift boat veteran, and Corsi, an expert on Vietnam antiwar movements, show how Kerry misrepresented his wartime exploits and is therefore incompetent to serve as commander in chief. Buttressed by interviews with Navy veterans who patrolled Vietnam's waters, some along with Kerry, readers will discover how he exaggerated minor injuries, self-inflicted others, wrote fictitious diary entries and filed "phony" reports of his heroism under fire—all in a calculated quest to secure career-enhancing combat medals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unfit For Command by John E. O'Neill,Jerome R. Corsi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

JOHN KERRY IN VIETNAM

ONE

DEBATING KERRY

John O’Neill

June 1971

In spring 1971, I was stationed at the Naval ROTC Unit at Holy Cross College in Massachusetts. After eight years away, I was desperate to return home to Texas. My father, a retired rear admiral, had suffered two heart attacks and was quite ill. Texas was also a place that I loved.

When I turned on the news that spring evening, I was sickened by what I saw—a broadcast of extracts from John Kerry’s testimony in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He compared those of us who served in Vietnam to the army of Genghis Khan, committing war crimes such as rape and baby-killing “on a day-to-day basis with the full awareness of officers at all levels of command.” I knew (as Kerry did) that he was lying about our Swift Boat unit and about the war in general. I was overwhelmed by the greatest sense of injustice that I had ever experienced—the memory of that night still haunts me today. I remembered my friends who served in Vietnam, living and dead, from the Naval Academy and from Swift Boats, and how hard we had tried to avoid civilian casualties under terrible conditions, at considerable risk to ourselves. I remembered those wounded and killed on the Dam Doi river, some of whom I watched die, because we broadcast messages of hope and freedom, urging villagers (many of whom were held in these villages by the Viet Cong against their will) to Chu Hoi. Moving at slow speeds, we were sometimes shot at—and some of us died. I remembered the fighter pilots who had been killed or were captured because we used small planes and opted for precision bombing in Hanoi, Haiphong, and the North Vietnam river dikes, rather than massive, indiscriminate bombing with B-52s, as we had done in World War II. That night, I resolved that I would refute Kerry’s lies.

John Kerry would like many people today to view his service in Vietnam as one of honor and courage. But the real John Kerry of Vietnam was a man who filed false operating reports, who faked Purple Hearts, and who took a fast pass through the combat zones. From the Revolutionary War to the present, politicians of both parties have attempted to garner political gain through association with wars and warriors. Kerry was another politician posing briefly as a warrior to acquire military credentials. His tour of Vietnam had been so very brief that he was disparagingly called “Quick John.” He was rarely talked about when I was in Vietnam, but I had heard that he wounded himself and others with M-79 rounds, but I had never fully investigated that until spring 2004.

If John Kerry had just been another politician punching his ticket in the military, I wouldn’t have cared. But for John Kerry to lie at the expense of his former comrades living and dead, in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, just so he could outbid other radicals in the antiwar movement and gain attention was something else. Even his own crew members who now (after long persuasion) support him for president were “pissed” at the time. They “knew he was dead wrong,” and their stomachs “turned” listening to Kerry speak and felt “disappointed and betrayed.”1 Millions of Vietnam veterans will never forget Kerry’s spinning of lies—lies so damaging to his comrades but so profitable to himself.

I wrote to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which at the time was headed by antiwar activists like J. William Fulbright. Since I spent far longer than Kerry in Vietnam and had seen far more combat, I asked in my letter for a few minutes to reply to Kerry’s lies and those of fellow purported antiwar Vietnam veterans. I received a letter in response, telling me that there was no room for another speaker. Nor was there room in most of the national media for any of the millions of us who felt differently from Kerry and his nine hundred radical “brothers”—many of them impostors who had never even been to Vietnam. Al Hubbard, the executive director of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, while Kerry was the group’s national spokesman, received far more coverage on all three networks as a “wounded fighter pilot” until it was revealed that Hubbard was a sergeant who had never served in Vietnam, claiming a back injury from basketball.

After Kerry’s testimony in May 1971, I read a short piece by Bruce Kesler, in the New York Times. In this article, Bruce, then a young ex-Marine just returned from Vietnam, maintained that Kerry was not speaking for the majority of Vietnam veterans in his speeches criminalizing our troops. Bruce was an enlisted Marine from one of the toughest parts of Brooklyn. When I finally reached him, he invited me to a press conference held by the Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace at the National Press Club. The purpose of the press conference was to counter Kerry’s war-crimes charges and challenge him to debate. I met Bruce the day before the press conference in the Washington, D.C., YMCA, where the group (given its limited finances) was staying. This was a stark contrast to the Georgetown townhouse in which Kerry the revolutionary stayed while in Washington.

Our press conference was surprisingly well attended. In it, I identified Kerry as a member of my unit, and I challenged him to a debate. We got some coverage, although far less than Hubbard and Kerry’s revolutionary band of VVAW activists did. I worked closely with Bruce and later spent a pleasant night or two with him and his gracious mother. Although our backgrounds could not have been more different, we share to this day a passionate love of human freedom, a dislike for totalitarian regimes of whatever stripe, and sickness and revulsion at the injustice of Kerry’s lies.

The media has recently attempted to paint our efforts to debate Kerry as a Nixon plot. The media relies on self-serving comments by Nixon aides taking credit for our group’s appearance. But the truth is that while we were supportive of Nixon’s “peace with honor” withdrawal from Vietnam (as opposed to a pullout that would leave our POWs behind), we were largely Democrats or apolitical, and our principal assets, other than a few contributions, consisted of the money I had set aside for law school and Bruce’s mother’s telephone.

While I delivered companion speeches alongside Kerry at the National Conference of Mayors, he turned down numerous debate offers from CBS’s 60 Minutes and many other forums. Finally, Dick Cavett offered his show, which Kerry accepted because Cavett was a friend and shared his antiwar position.2

Tour of Duty and Kerry’s spin machine have attempted to deflect attention from his disastrous performance in the Dick Cavett Show debate by claiming there was a plot by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Charles Colson, or Richard Nixon. This is ridiculous. Kerry performed disastrously because he was lying about his war-crimes claim, and it was obvious to anyone, including the audience, which, as Dick Cavett observed, was solidly on his side at the beginning but booing him at the end.

I did meet with Richard Nixon, and also with many Democratic representatives and members of Congress, such as Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson and Congressman Olin Earl “Tiger” Teague, who encouraged me not to give up and to do my best. Unknown to me at the time, an actual tape and transcript of my meeting with Nixon are available today. The meeting begins with me telling President Nixon that although my family and I were Democrats who voted for Hubert Humphrey, we supported Nixon on the issue of a phased withdrawal from Vietnam. And I remember even now the gasps at the meeting following my comment and my vague feeling that I must have done something inappropriate.

Since the debate was proposed by Dick Cavett, who was on Nixon’s “enemies” list and whose show was accepted by Kerry as a friendly forum, it is more than a little disingenuous to present Kerry’s debacle as a Nixon or a VFW plot. I obviously did not need any encouragement from Nixon, Colson, Senator Jackson, or anyone else. I had plenty of encouragement from the fifteen or so of my friends labeled “war criminals” by Kerry and whose names are carved today in the dark V of the Vietnam Memorial. I continue to think of them often as young men who had bright futures, not simply names on a dark wall. I also received encouraging calls from many Swiftees, like my closest friend, Elmo Zumwalt III. I’ve always been proud that while Kerry wanted letters of support for him from members of our unit to wave against me in the debate, he was only able to get one such letter.

I debated Kerry on June 30, 1971. The debate received high ratings, and Cavett has recalled it as one of the most memorable of his distinguished shows.

While Tour of Duty seeks to present the show as a victory for Kerry, citing the only known article so stating, it was in reality a debacle for him and his radical VVAW buddies. Our respective hometown newspapers, the Boston Globe (Kerry’s) and the San Antonio Express (mine), agreed that Kerry had suffered a heavy loss. And in the White House, people were thrilled.3 Much more important to me than politicos or newspapers were my fellow Vietnam veterans, Swiftees, and the widows and children of my friends who had died in Vietnam. All of them thought that I had won the debate. In 1977, I was particularly proud to be thanked by Lieutenant General John Flynn who learned of the debate after his release. A senior U.S. POW in Vietnam, he had been confronted while in captivity with Kerry’s war-crimes charges. To the audience that mattered to me, I won.

When the debate opened, I concentrated primarily on these war-crimes charges. They were far more important than the geopolitical opinions of two young vets, one of whom had been in Vietnam for only four months. I ended my opening statement by quoting Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol:

And all men kill the thing they love, . . .

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

For me, that quotation summed all I knew then and know now of John Kerry—a self-promoted war hero who in reality was the greatest moral coward I had ever met, willing to sell out friends and comrades for political fame. Kerry’s response was “Wow. Well, there are so many things really. . . .” I was surprised because I realized that Kerry was not insulted by my comments. For him, our debate was simply another game of political calculation. The questions of right and wrong, good and evil, played no real role in his thinking; he simply said whatever sounded popular. Lying about his friends on one hand, or being called a moral coward on the other, had little impact on a person whose only values were political or ideological calculations. Fortunately, a videotape of the debate survives. Anyone who wishes to understand John Kerry should view it. You won’t find it on Kerry’s website, but it is available at www.WinterSoldier.com (transcript), C-SPAN, and other websites.

That day, I repeatedly asked Kerry to list any war crimes or atrocities committed in our unit, Coastal Division 11.4 He named generalities such as harassment and interdiction fire zones (commonly known as “H&I fire zones”) and free-fire zones. A free-fire zone in Vietnam was an area in which one had discretion to fire if enemy were sighted, without first checking with headquarters. It required restraint and was not a war crime. Likewise, H&I meant firing at enemy positions in order to secure passage, or in the case of the Ho Chi Minh trail, interdict supplies. None of these activities would be regarded by any normal military expert as a war crime then or now.

Shockingly, when I directly confronted him about our small unit, Coastal Division 11, and his claims of war crimes there by our comrades, Kerry essentially collapsed and was unable to list a single “personal atrocity,” as he labeled it, that he had actually witnessed—a remarkable concession from the “King of the Vietnam Veterans as War Criminals.” When face to face across a table with someone from exactly the same unit, Kerry could not come up with a single instance of any atrocity in our unit or that he himself had actually seen in Vietnam. The reason that he could not describe any atrocities was because there were no atrocities.

Near the end of the debate, and in a rare moment of departure from Dick Cavett’s genuine effort to serve as an impartial moderator, Cavett asked whether either of us believed in the “cliché” that a bloodbath would occur if the United States were to withdraw from Vietnam. I answered that I thought that there would be a bloodbath, given the assassinations that we saw in the Can Mau region and the executions by the Viet Cong of South Vietnamese soldiers whose bodies we recovered in rivers and canals. Kerry answered in substance that it would never occur, that at most there might be five thousand people killed—a number so small that it was “lunacy” to talk about it. Some 3.5 million people are estimated to have died in the Communist purges at the end of the Vietnam War, including the 2.5 million in the killing fields of Cambodia. In Laos, whole peoples were eliminated. There were 1.4 million refugees, many of whom made it to the United States. Tens of thousands of “boat people” perished at sea trying to escape. I often wonder if Kerry is haunted (as I am) by his answer and by the thought of those lost souls, who once loved and lived and experienced the joys of life, but whom he so casually dismissed that day.

In the opinion of a recent biography of Kerry, that debate marked Kerry’s high-water mark for many years, and after the debate “as quickly as Kerry’s star had risen, it began to fade.” Other than a failed congressional run (a campaign that I had predicted in the debate and that Kerry had denied) in w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: John Kerry in Vietnam

- Part II: Antiwar Protester

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index