- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

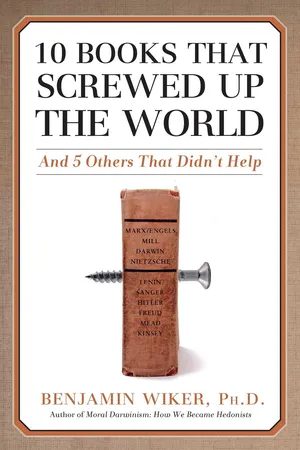

About this book

You’ve heard of the "Great Books"? These are their evil opposites.

From Machiavelli's The Prince to Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, from Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto to Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa, these "influential" books have led to war, genocide, totalitarian oppression, the breakdown of the family, and disastrous social experiments.

And yet the toxic ideas peddled in these books are more popular and pervasive than ever. In fact, they might influence your own thinking without your realizing it.

Fortunately, Professor Benjamin Wiker is ready with an antidote, exposing the beguiling errors in each of these evil books.

Witty, learned, and provocative, 10 Books That Screwed Up the World provides a quick education in the worst ideas in human history and explains how we can avoid them in the future.

From Machiavelli's The Prince to Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, from Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto to Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa, these "influential" books have led to war, genocide, totalitarian oppression, the breakdown of the family, and disastrous social experiments.

And yet the toxic ideas peddled in these books are more popular and pervasive than ever. In fact, they might influence your own thinking without your realizing it.

Fortunately, Professor Benjamin Wiker is ready with an antidote, exposing the beguiling errors in each of these evil books.

Witty, learned, and provocative, 10 Books That Screwed Up the World provides a quick education in the worst ideas in human history and explains how we can avoid them in the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 10 Books that Screwed Up the World by Benjamin Wiker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Literacy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Preliminary Screw-Ups

dp n="15" folio="6" ?dp n="16" folio="7" ? CHAPTER ONE

The Prince (1513)

“Hence it is necessary to a prince, if he wants to maintain himself, to learn to be able not to be good. . . . ”

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)

YOU’VE PROBABLY HEARD THE TERM MACHIAVELLIAN AND ARE AWARE of its unsavory connotations. In the thesaurus, Machiavellian stands with such ignoble adjectives as double-tongued, two-faced, false, hypocritical , cunning, scheming, wily, dishonest, and treacherous. Barely a century after his death, Niccolò Machiavelli gained infamy in Shakespeare’s Richard III as the “murdrous Machiavel.” Almost five hundred years after he wrote his most famous work, The Prince, his name still smacks of calculated ruthlessness and cool brutality.

Despite recent attempts to portray Machiavelli as merely a sincere and harmless teacher of prudent statesmanship, I shall take the old-fashioned approach and treat him as one of the most profound teachers of evil the world has ever known. His great classic The Prince is a monument of wicked counsel, meant for rulers who had shed all moral and religious scruples and were therefore daring enough to believe that evil—deep, dark, and almost unthinkable evil—is often more effective than good. That is really the power and the poison of The Prince: in it, Machiavelli makes thinkable the darkly unthinkable. When the mind is coaxed into receiving unholy thoughts, unholy deeds soon follow.

Niccolò Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy, on May 3, 1469, the son of Bernardo di Niccolò di Buoninsegna and his wife, Bartolemea de’ Nelli. It is fair to say that young Machiavelli was born into wicked times. Italy was not a single nation then, but a rat’s nest of intrigue, corruption, and conflict among the five main warring regions: Florence, Venice, Milan, Naples, and the Papal States.

Machiavelli witnessed the greatest hypocrisy in religion, including cardinals and popes who were nothing more than political wolves in shepherds’ clothing. He also knew firsthand the cold cruelty of kings and princes. Suspected of treason, Machiavelli was thrown into jail. To elicit his “confession,” he was subjected to a punishment called the strappado. His wrists were bound together behind his back and attached to a rope hanging from a ceiling pulley. He was hauled up in the air, dangling painfully from his arms, and suddenly dropped back to the ground, thereby pulling his arms out of their sockets. This delightful process of interrogation was repeated several times.

Machiavelli knew evil. But then, so did many others, in many other times and places. There is no shortage of wickedness in the world, and no shortage of witnesses to it. What makes Machiavelli different is that he looked evil in the face and smiled. That friendly smile and a wink is The Prince.

The Prince is a shocking book—artfully shocking. Machiavelli meant to start a revolution in his readers’ souls, and his only weapons of revolt were his words. He stated boldly what others had dared only to whisper, and then whispered what others had not dared even to think.

Let’s look at Chapter Eighteen for a taste. Should a prince keep faith, honor his promises, work above board, be honest, that kind of thing? Well, Machiavelli muses, “everyone understands” that it is “laudable . . . for a prince to keep faith, and to live with honesty.”1 Everyone praises the honest ruler. Everyone understands that honesty is the best policy. Everyone knows the countless examples in the Bible of honest kings being blessed and dishonest kings cursed, and ancient literature is filled with tributes to virtuous sovereigns.

But is what everyone praises truly wise? Are all good rulers successful rulers? Even more important, are all successful rulers good? Or does goodness, for a ruler, merely mean being successful, so that whatever leads to success—no matter what everyone may say—must be good by definition?

Well, says Machiavelli, let’s see what actually happens in the real world. We see “by experience in our times that the princes who have done great things are those who have taken little account of faith.” Keeping your word is foolish if it brings you harm. Now, “if all men were good, this teaching would not be good; but because they are wicked and do not observe faith with you, you also do not have to observe it with them.”

But keeping one’s word is not the only thing that should be cast aside for convenience. The whole idea of being good, Machiavelli assumes, is rather naïve. A successful prince must concentrate not on being good, but on appearing to be good. As we all know, appearances can be deceiving, and for a prince deception is a good thing, an art to be perfected. A prince must therefore be “a great pretender and dissembler.”

And so, one might ask, should a ruler be merciful, faithful, humane, honest, and religious? Not at all! It is “not necessary for a prince to have all the above-mentioned qualities, but it is indeed necessary to appear to have them. Nay, I dare say this, that by having them and always observing them, they are harmful; and by appearing to have them they are useful.” So it is much better, more wise, “to appear merciful, faithful, humane, honest, and religious,” but if you need to be cruel, faithless, inhumane, dishonest, and sacrilegious, well, then, necessity is the mother of invention, and you should invent devious ways to do whatever evil is necessary while appearing to be good.

Let me offer two examples of Machiavelli’s advice in action, the first taken from The Prince, and the other from our own day. A more wicked man than Cesare Borgia—whom Machiavelli knew personally—could hardly be imagined. He had been named a cardinal in the Catholic Church, but resigned so he could pursue political glory (and did so in the most ruthless way). Borgia was a man without conscience. He had no anxiety whatsoever about inflicting great cruelties to secure and maintain power. Of course, this gave him a bad reputation with his conquered subjects, creating the kind of bitterness that soon leads to rebellion. In Chapter Seven Machiavelli sets before his reader an interesting practical lesson on Borgia’s method of dealing with this problem.

One of the areas Borgia snatched up was Romagna, which Machiavelli notes was a “province . . . quite full of robberies, quarrels, and every other kind of insolence.” Of course, Borgia wanted “to reduce it to peace and obedience,” because it is hard to rule the unruly. But if he brought them into line himself, the people would hate him, and hatred breeds rebellion.

What did Borgia do? He sent in a henchman, Remirro de Orco, “a cruel and ready man, to whom he gave the fullest power.” Remirro did the dirty work, but of course this got him dirty. The people hated Remirro for his attempts to crush their rebellious and lawless spirit and make them obedient subjects. But as Remirro was obviously working as Borgia’s lieutenant, Borgia would be hated too.

But Borgia was an inventive man. He knew that he needed to fool the people into believing that “if any cruelty had been committed, this had not come from him but from the harsh nature of his minister.” And so, Borgia had Remirro “placed one morning in the piazza at Cesena [cut] in two pieces, with a piece of wood and a bloody knife beside him. The ferocity of this spectacle left the people at once satisfied and stupefied.”

Satisfied and stupefied. The angry people of Romagna were happy to see the agent of Borgia’s cruelty suddenly appear one sunny morning hewn in half in the town square. Borgia himself had satisfied their desire for revenge! But at the same time they were numbed into obedience by a completely unexpected spectacle of ingenious brutality.

The reader’s imagination gropes after an image of the horror. A man sawed in half. Lengthwise or crosswise? A bloody knife. Simply lying beside the body? Thrust into the block of wood? Could a mere knife hack a man in two? And why a block of wood? A butcher’s block?

One thing is certain: Machiavelli does not blame Borgia for his ingenious cruelty, but praises him. He very cleverly appeared to be humane by hiding inhumanity, to be merciful by concealing mercilessness. “I would not know how to reproach him,” Machiavelli says of Borgia’s lifelong career of similar dastardly actions. “On the contrary, it seems to me he should be put forward, as I have done, to be imitated by all those who have risen to empire through fortune.”

One does not always need to be as viciously picturesque as Borgia to follow Machiavelli’s advice. As anyone who watches our own political scene well knows, we quite often witness the less bloody (but no less well calculated) spectacle of an underling to a president or congressman immolating himself publicly to take the heat off his boss. Behind the elaborately staged appearances, the underling—like poor Remirro, who was merely carrying out the chief’s orders—is being sacrificed to satisfy and stupefy the electorate.

This brings us to our second example of Machiavellianism in action. “A prince should thus take care,” notes Machiavelli, returning to his list of virtues, “that nothing escape his mouth that is not full of the above-mentioned five qualities” so that “he should appear all mercy, all faith, all honesty, all humanity, all religion. And nothing is more necessary to appear to have than this last quality.” It is most important that rulers—and even more so, would-be rulers—appear to be religious. “Everyone sees how you appear,” but “few touch what you are,” and appearing to be religious assures those who see you that, because you appear to believe in God, you can be trusted to have all the other virtues. In politics, some things never change.

But duplicity isn’t the only patrimony of Machiavelli’s The Prince. The damage is much deeper than that. The kind of advice Machiavelli offers in The Prince is only possible for someone to give (and to take) who has no fear of hell, who has discarded the notion of the human soul living on after death as a foolish fiction, who believes that since there is no God then we are free to be wicked if it serves our purposes. That is not to say that Machiavelli ever advises being evil merely for its own sake. He does something far more destructive: evil is offered under the excusing pretext that it is beneficial. Machiavelli convinces the reader that great evils, unspeakable crimes, foul deeds are not only excusable but praiseworthy if they are done in the service of some good. Since this advice occurs in the context of atheism, then there are no limits on the kind of evil one can do if he thinks he is somehow benefiting humanity. It should not surprise us that The Prince was a favorite book of the atheist V. I. Lenin for whom the glorious end of communism justified any brutality of means.

Since this will remain an important connection in most of the subsequent books we cover, we must dwell on the deep connections between atheism and the kind of ruthless advice Machiavelli gives. It is a fundamental principle of Christianity—the religion that defined the culture into which Machiavelli was born, and the religion he rejected—that it is never permissible to do evil in the service of good. You can’t lie about your credentials to get elected to office. You can’t kill an innocent baby to advance your career. You can’t start a war to boost the economy or your approval ratings. You can’t resort to cannibalism to solve the hunger problem. You can’t commit adultery to get a job promotion.

The source of this prohibition is obviously the fact that some actions are intrinsically evil. No matter the circumstances or the alleged or even actual benefits, some acts cannot be committed. Unfortunately, this is not the way we generally think today. When you suggest to someone that there are some intrinsically evil actions—so foul, so unholy, that even to think of doing them leaves a black mark on the soul—the usual response is a smirk, followed by a wildly contrived example that is supposed to force you into choosing some horribly evil deed to avoid even more horrible consequences. “What if a terrorist gives you a choice: either shoot and skin your grandmother or we’ll blow up New York.” The hidden assumption of the smirker is that, of course, the moral thing to do is save New York by shooting and skinning your grandmother, and that goes to show that there are no moral absolutes.

Of course, smirkers are rarely logical. If there really are no intrinsically evil actions, then it is quite fine to have New York blown up in order to save your grandmother. But the real point, for our purposes, is that the smirker is using precisely the mode of reasoning that Machiavelli uses in The Prince. Machiavelli is the original ends-justify-the-means philosopher. No act is so evil that some necessity or benefit cannot mitigate it.

But how is this all linked to atheism? Again, we must use the religion that historically defines the beliefs Machiavelli rejected. For the Christian, no earthly necessity or benefit can be weighed against eternity. Committing an intrinsically evil act immediately separates us from the eternal good of heaven, whatever the benefit that might accrue to us in the here and now. No good we experience now can possibly outweigh having to suffer eternally in hell. Furthermore, as God is all-powerful, then no seeming necessity or benefit of an evil action in this life can really be necessary or beneficial to anyone from the perspective of eternity. To believe otherwise is only a temptation; in fact, the temptation.

As we shall see in subsequent chapters, yielding to the temptation to do evil in the service of good will be the source of unprecedented carnage in the twentieth century, so horrifying that to those who lived through it, it seemed hell had come to earth (even though it was largely perpetrated by people who had discarded the notion of hell). The lesson learned—or that should have been learned—by such epic destruction is this: once we allow ourselves to do evil so that some perceived good may follow, we allow ever greater evils for the sake of ever more questionable goods, until we consent to the greatest evils for the sake of mere trifles.

Remove God, and soon there is no limit on evil at all, and no good is too trivial an excuse. Consider a report from the British newspaper The Observer three years ago: in the Ukraine, suffering so long under the atheist Soviet foot, pregnant women were being paid about $180 for their fetuses, which the abortion clinics turned around and sold for about $9,000. Why? The tissue was being used for beauty treatments. Pregnant women were and still are being paid to kill their babies so aging Russian women can rejuvenate their skin with fetal cosmetics.

But to return to Machiavelli, our point is this: to embrace the notion that it is not only permissible but also laudable to do evil so that good might come, one must reject God, the soul, and the afterlife. That is just what Machiavelli did, and that is the ultimate effect of his counsel.

Here it might be objected that Machiavelli appeared to be religious in his writings, casting out pious phrases here and there, and speaking with a certain respect (however strained and peculiar) about things religious. So, it is argued, because he appears to be religious, then we must give him the benefit of the doubt.

It is difficult for me to deal with this all too common objection because it shows a frightening woodenness to the obvious (let alone to the subtle) in Machiavelli. Did he not just tell us how important it is to appear to be religious? Who informed us of the necessity, if one is to be a great prince, of being a great pretender and dissembler? Who contrives to be a greater prince—the temporal ruler of a piece of land, or the philosopher who seeks to inform all future princes, to found an entirely new philosophy?

And so we repeat: Machiavelli could not give advice to princes that would mean abandoning any notion of God, the immortal soul, and the afterlife if he himself had not already abandoned all three. That is why he can call evil good, and good evil.

This is seen clearly in the famous Chapter Fifteen. Machiavelli tells the reader quite matter-of-factly that he is departing from the way all others have spoken about good and evil. He w...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part I - Preliminary Screw-Ups

- Part II - Ten Big Screw-Ups

- Part III - Dishonorable Mention

- AFTERWORD

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright Page