![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A GREAT,

SLOBBERING

LOVE AFFAIR

CONTINUED

Slate, the online magazine, has a laudable quadrennial tradition. Before each presidential election, its staffers disclose to the public how they intend to vote. The first year they did this, in 2000, Democrat Al Gore won 78.4

The first year they did this, in 2000, Democrat Al Gore won 78.4 percent of their support, and Republican George W. Bush won 10.8 percent.1 In 2004, John Kerry had the backing of 84.9 percent of Slate’s staff.2

In 2008, Barack Obama was backed by fifty-five staffers out of fifty-eight, and John McCain by just one. (Another respondent answered merely, “Not McCain.”)3 As you may recall, Obama got a bit less than 94.8 percent from the general population in that election. In 2012, Obama again received a much smaller share of the popular vote than the 83.8 percent that Slate’s staff gave him.4

I admire Slate for disclosing how its writers vote, providing a look inside the minds of political journalists whose work I enjoy. But obviously, what stands out here is their degree of ideological uniformity.

It isn’t just Slate. In 1981, academics S. Robert Lichter and Stanley Rothman, who later wrote The Media Elite, surveyed 240 journalists at some of the nation’s most prestigious national media organizations. They found that four in five, 80 percent, had voted Democratic in all four of the presidential elections between 1964 and 1976, including the Nixon landslide of 1972.5 Rothman followed up with a similar survey in 1995 and found that 91 percent of journalists had voted for Bill Clinton in 1992—a year when he received just 43 percent of the popular vote.6

When it comes to their political giving, journalists are even more slanted. In 2008, William Tate of Investor’s Business Daily found that twenty journalists gave to Obama for every one who gave to John McCain.7 Political Moneyline (now CQ Moneyline) found in July 2004 that ninety-three journalists gave to John Kerry for every one who gave to George W. Bush.8

It would be too much to expect newsrooms to look—politically speaking—like America does. But 90 percent voting Democrat? It’s difficult to get that many people in a poll to say they like apple pie.

Journalism is one of the most influential professions, and also one of the most thoroughly and consistently politically lopsided. The media have a political party, and they are far more loyal in their partisanship than many of the voter blocs that probably come to mind when you think of partisan loyalty: Evangelical Christians, union members, Mormons, atheists—all of those groups are bastions of independent thought compared to journalists when it comes to their political thinking and voting patterns.

It’s More Than Bias

Conservatives often overdo it when they criticize media bias. They find it in every unfavorable story and sometimes in places where it doesn’t matter. I’ll say it: they whine too much. But that doesn’t mean they’re wrong. Former CBS News reporter Bernard Goldberg put it this way in Bias (2001), his seminal and bestselling book:

Some right-wing ideologues do blame “the liberal news media” for everything from crime to cancer. But that doesn’t detract from another truth: that, by and large, the media elites really are liberal. And Democrats, too. And both affect their news judgment.9

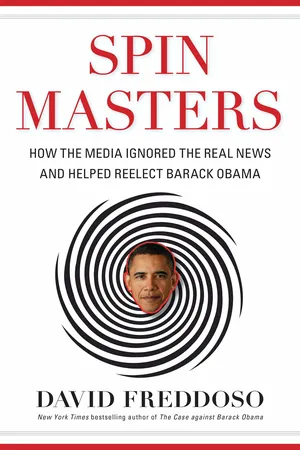

Bias was one of the first books I read after coming to Washington in 2001. There’s a reason it made number one on the New York Times bestseller list and stayed on the list for nineteen weeks, seven of them in the top slot. It provided an insider’s confirmation of a very real phenomenon—liberal media bias—that had irked conservatives for decades. Bias provided concrete examples of the subtle and overt ways that media bias affects coverage of the issues of the day.

Thanks to works like The Media Elite and Bias, and organizations like the Media Research Center, Americans aren’t really surprised anymore when they hear, say, a story about a room full of reporters at a presidential debate cheering at a good Obama debate line, as they did on October 17, 2012.10

A participant in one of Frank Luntz’s post-debate focus groups might have been a bit foul-mouthed but he was not alone when he complained about the media’s role in creating, promoting, and propping up the Obama presidency:

That’s why I voted for him [in 2008]. I bought his bull. And he’s lied about everything, he hasn’t provided, he hasn’t come through on anything, and he’s been bullsh--ting the public with the media behind him.11

Most journalists claim that they report the news as it is, and that they do not allow their personal political beliefs to influence how they report it. Objectivity, every aspiring reporter is taught, is a first principle of journalism. That is true even for opinion journalists and commentators, who also have a responsibility to present facts in a reasonable, honest way—and who, at their best, make a point of confronting facts that are inconvenient to the positions they take.

But no one is without biases. Any journalist, liberal or conservative, can report facts fairly. Even so, any journalist who thinks he’s perfectly unbiased is only deceiving himself.

The political coverage in 2012 was very biased. This book will explore many of the stories that bias prompted the media to ignore, and others that it prompted the media to tell ad nauseam despite their relative lack of importance.

Why does this happen? As Goldberg writes in both Bias and his 2009 book, A Slobbering Love Affair, it’s not that the heads of the media world are in some tall Manhattan building, consciously trying to slant the news and help the political party they like. They are more often prisoners to their own worldview, unable to recognize a good story (or its significance) if it falls outside of it. And this organic, institutional bias is further reinforced by their colleagues’ ideological uniformity. If they are exposed to any conservative arguments at all, they are usually weak and poorly grounded ones. As Goldberg put it:

The problem, in a word, is groupthink. There simply are too many like-minded people in America’s most important newsrooms, and like-mindedness has a way of reinforcing biases. . . .

. . .Yes, it is theoretically possible for journalists to be overwhelmingly liberal, and to overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates for president, and still be fair and objective in their journalism. But realistically, and in practice, there’s no way. That liberal bias seeps into just about everything the media touch. The problem is that life inside the liberal media bubble is too comfortable. It dulls the senses. It turns even well-educated journalists into narrow-minded provincial rubes. . . . It lulls journalists into thinking that they really are fair and honest brokers of information.12

If Goldberg’s talk of narrow-mindedness seems too strong, think back to the most spectacular journalistic failure of this century. Dan Rather’s downfall in 2004 came as a result of his instinctual willingness to believe anything negative about George W. Bush—anything! When a document of dubious provenance fell into his lap (it purported to document a backroom political deal that won Bush special treatment during the Vietnam War), he put it on the air with hardly a second thought.13 When you’re certain enough about your conclusion, any proof will do.

One can certainly fail without failing as dramatically as Rather did. An instinctual unwillingness to believe anything bad about a president results in journalistic failures, too—failures that don’t end careers, but that do result in important stories never being told, and in journalists bending over backwards to defend politicians they like in a way they never would for politicians they don’t like.

The flashy meltdowns on national television—the moments when overt bias spills over into coverage—have a very high entertainment value. They can be ridiculous and embarrassing for all involved. The 2012 election saw its fair share, and many will be discussed in this book.

But this book is not just about the awkward Obama cheerleading that occurred in some segments of the leg-tingling media. The deeper problem is the more subtle one. At the highest levels of journalism, editorial judgments are made about what matters and what deserves coverage. And yes, facts are facts, but their significance may not be obvious to someone whose view of the world is sufficiently one-dimensional.

In the coverage of the 2012 presidential race, news judgments generally sided with fluff, often coming straight from President Obama’s campaign, over substance. This made campaign coverage, in a word, stupider. It also made it a lot more helpful to Obama. The parade of bright shiny objects that distracts from the pain voters feel—of economic failure, of seeing their money wasted by a government that’s taking away their freedoms and claiming new, unprecedented powers every day—is exactly what an incumbent with a shaky record needs most.

On his trip to Poland in late July 2012, GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney visited the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw—a solemn site filled with more sorrowful and painful memories than Americans have at Arlington Cemetery. The American press, roped off at a distance, shouted out—or really, whined out—their profound questions after him. Here were three of the five:

CNN: “Governor Romney are you concerned about some of the mishaps of your trip?”

Washington Post: “What about your gaffes?”

New York Times: “Governor Romney do you feel that your gaffes have overshadowed your foreign trip?”14

Ladies and gentlemen, that was your media during Campaign 2012. The CNN journalist then shouted out a fourth question, noting that Romney hadn’t been taking many questions from the press during his trip to Europe. But if these were the kind of questions they were asking, it’s hard to see this as a big loss. How would Romney have even answered? “I am quite concerned about my gaffes”? Or perhaps: “My gaffes are the best gaffes; that’s what I like about them”?

Yes, there was good journalism done in 2012. There were keen insights and hard-hitting stories published. But on aggregate, the press let the public down. And the public noticed.

The Pew Center for Excellence in Journalism released its postelection scorecard poll on November 15. The press received a gentleman’s C-minus—the lowest of any entity graded, and a lower grade than either campaign. But that wasn’t the most significant finding. In 2008, 57 percent of respondents told Pew that there was “more discussion of the issues than usual” during the election. In 2012, only 38 percent thought so, and 51 percent thoug...