- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

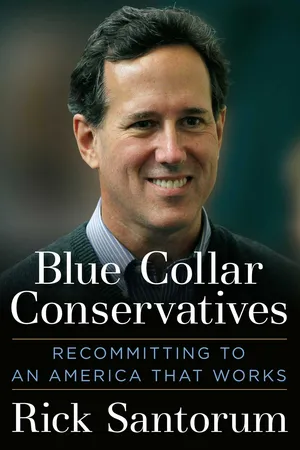

About this book

Before Donald Trump successfully mobilized millions of blue collar Americans with his campaign to reclaim America, Rick Santorum was trying to convince his fellow Republicans that it was time to return to the party’s original values: the values of “blue collar conservatives.”

In this powerful book that helped inspire President-Elect Trump’s winning message to voters, Santorum calls out Republican establishment leaders for pandering to business owners at the expense of everyone else. Republicans need to regain the trust of the hard-working members of every family, church, and community across America whose most immediate problems are lack of jobs and opportunity. No more pandering. No more ignoring those left behind by globalization. No more broken promises to the frustrated middle class.

We're entering a brand new era of conservative politics—and Rick Santorum's Blue Collar Conservatives shows us the way forward.

In this powerful book that helped inspire President-Elect Trump’s winning message to voters, Santorum calls out Republican establishment leaders for pandering to business owners at the expense of everyone else. Republicans need to regain the trust of the hard-working members of every family, church, and community across America whose most immediate problems are lack of jobs and opportunity. No more pandering. No more ignoring those left behind by globalization. No more broken promises to the frustrated middle class.

We're entering a brand new era of conservative politics—and Rick Santorum's Blue Collar Conservatives shows us the way forward.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blue Collar Conservatives by Rick Santorum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

BLUE COLLAR CONSERVATIVES REALLY DID BUILD IT

There was a time not long ago when Americans without college degrees could expect to earn a decent and steady income in exchange for hard work. This income and job stability provided a foundation for families and communities that, with their churches, Little Leagues, Boy Scout troops, and a hundred other civic organizations, fostered the strong values and the work ethic that underpinned American life. Millions of Americans came of age in these communities and took those values with them as they started their own families and thanked God for his blessings. With good incomes, Americans could afford new cars, kitchen appliances, and trips to Disneyland. Demand for such new goods kept others working and employment strong. With stable marriages, children enjoyed the gift of security and neighborhoods where values were taught at home and in church and enforced by parents.

This is how I grew up. My grandparents came here from Italy in 1930, fleeing fascism and settling in a coal town in the hills outside of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. That’s where they found freedom and the opportunity to earn decent pay for hard work in the mines. They found a gritty but overall wholesome place to raise their kids and taught them that in America there was no limit to what they could become. I know the American Dream was real because my grandparents lived it.

Their son Aldo, my father, was seven when his family left Italy for America. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in the South Pacific in World War II, and when he came home from the war, he earned advanced degrees in clinical psychology. He worked for the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) counseling World War II, Korea, and Vietnam vets for almost forty years. At his first post, in Martinsburg, West Virginia, he met and married my mother, Catherine, an administrative nurse. I was born in 1958, the second of three children. Unlike most mothers at that time, my mother continued to work as a nurse. It was a great setup because the hospital where she worked was a stone’s throw from our house. My siblings and I spent our childhoods living in various rented World War II–era buildings, including the post jail that had been converted into apartments. When I was seven, we returned to western Pennsylvania and settled in Butler, among the mines and steel furnaces that were the economic bedrock of that part of the country.

I went to Butler Catholic Grade School and then Butler High School. Like other kids, I played (but not well) both baseball and basketball, and I saw my first major league game, between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Cincinnati Reds, at Forbes Field. As in most small towns in America back then, families kept their doors unlocked. Kids roamed neighborhoods freely, but there was always a parent nearby, and they didn’t hesitate to enforce the values of the community. And though I wasn’t aware of this at the time, this world was possible in part because Butler made stuff. While my dad didn’t work in the mill, almost all of my friends’ dads did. That and numerous school field trips to local plants drove home the importance of manufacturing to our community. We had thriving manufacturers like the Pullman-Standard Company, which made railroad cars (it was shuttered in the 1980s and demolished in 2005), and an Armco steel plant, which is now AK Steel. There was a job for virtually anyone out of high school who was willing to work an honest day. And those jobs carried benefits and security that formed the core of the community. Looking back, it’s not a very complicated equation.

Those field trips and conversations with my friends’ dads were extra motivation for me, and many others, to hit the books in school. It was clear then that change was afoot with automation and global competition, so I headed off to Penn State University, where I fell in love with Penn State Nittany Lions football, drank my share of Rolling Rock beer (after I turned twenty-one, of course), and found my vocation in politics and public service. I worked on campaigns and ended up founding the College Republicans club on campus.

After Penn State, I got an MBA degree from the University of Pittsburgh, worked for a couple of years, went back to law school, and became an attorney in Pittsburgh. Three years later, I met my future wife, Karen Garver, who was a neonatal nurse and law student. In 1990, at age thirty-one, I left my law firm to run for Congress, serving two terms in the House of Representatives before running for the U.S. Senate. In all, I represented Pennsylvania in Congress for sixteen years, from 1991 to 2007. And during those years, Karen and I had eight children. We gave them the basics: the security of a good marriage, our time schooling them at home, and faith in our Lord and Savior.

I’ve gone pretty far on the steel-town values of education, working hard, loving your family, and living your faith. That doesn’t mean that we’ve never had problems. We’ve had more than our share, but my family, and our neighbors, schoolmates, teammates, and church members, has shared a common belief that we needed to look out for one another and be there when we were needed. Getting help from the government wasn’t something you wanted—or wanted anyone to know that you had—and you took it only when you absolutely needed it. And even then, you didn’t take it for very long.

There are remnants of that America in some small towns and tight-knit neighborhoods. But my travels during the presidential campaign have sadly reminded me that many of the jobs that were once the basis of those communities for the 70 percent of Americans who don’t have college degrees are all but gone. Over the past few decades, bad corporate and labor leadership, a growing regulatory burden, and competition from low-wage countries have made America less competitive and jobs harder to come by. Economists turn this reality into statistics and tell us that we’re moving from a manufacturing to a service economy and that while the old jobs are gone, new ones will come. But with those old jobs gone, the toll has been more than economic; its effect on families and communities has been devastating.

Much has been made of a January 2014 study by a group of distinguished economists from Harvard and the University of California at Berkeley that appears to refute the common perception that it’s harder to get ahead in America than it used to be.1 Examining forty years of data on economic mobility and inequality, the Equality of Opportunity Project found that “[c]hildren entering the labor market today have the same chances of moving up in the income distribution (relative to their parents) as children born in the 1970s.”2 Republicans, however, should resist the temptation to dismiss all the talk about declining mobility as another hyped-up crisis—like global warming—and settle back to our old economic policies. For one thing, upward mobility varies greatly from community to community in America. Not surprisingly, it’s the lowest in rural and depressed areas. The poorest kids in San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Salt Lake City, for example, are more than twice as likely to reach the highest income percentiles as those in Dayton, St. Louis, and Charlotte. And while our economic mobility rate has not changed substantially over time, it is lower than in other developed countries. Think about that—in upward mobility, the Land of Opportunity is falling behind the rest of world.

Digging a little deeper, the study reveals that globalization and automation in manufacturing and the breakdown of families and communities—circumstances that contribute to economic inequality—have been counterbalanced by a healthier environment, technological advancements that produce better living standards, and more opportunities for women and minorities. But ever-increasing automation and the additional loss of jobs to global competition are without question steepening the incline for lower-educated and lower-skilled workers, particularly men, and their families.

When I campaigned for president in 2012, I was pigeonholed by the media as the “social conservative” candidate who only talked about abortion, marriage, and, of all things, contraception. Anyone who actually bothered to show up to one of those 381 town hall meetings in Iowa or any of my hundreds of other talks around the country would know what an inaccurate characterization that was. But my coming out of nowhere with no money to win the Iowa caucuses, where social conservatives make up a large percentage of the vote, reinforced that caricature. What the uninformed “experts” sitting in New York and Washington didn’t realize was that my stance on moral issues didn’t differentiate me from the field. It was how I integrated those issues into the central discussion of improving our economy.

In a debate at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, I got the chance to take that message to a national audience. I explained that the word “economy” comes from “oikos,” the Greek word for family. The family is the first economy, and healthy marriages lead to financial success and stability in an overwhelming percentage of cases. It’s no coincidence that the Equality of Opportunity Project concluded that family structure was the most important determinant of upward mobility. Children raised in single-parent households are the least likely to climb the ladder of success, followed by children raised in two-parent families who live in communities of mostly single parents.

Today, marriage rates are at a historical low while illegitimacy is at a historical high.3 And just as marriage—an institution older than any government and the foundation of a stable society—has fallen into this crisis, activist courts are redefining it in a way that extinguishes whatever meaning it had left. Let me be clear—I am not blaming the breakdown of marriage and the family on the same-sex marriage movement. The sexual revolution has been taking a jackhammer to that foundation for fifty years. No one would be talking about same-sex marriage if we had not lost the real meaning and purpose of marriage years ago.

Working Americans are now finding fewer and fewer of the opportunities that we once took for granted. Sure, they might find a good job in the lumber department at Home Depot or driving a delivery truck for FedEx, but long-term, steady employment opportunities—the kind that can support a family—appear to be gone for many Americans. In too many towns, the disappearance of quality jobs has brought not only economic hardship but a host of social pathologies, from alcohol and drug abuse to petty crime, obesity, and dependence on welfare. The teenage mother, the drug addict, or the convicted felon who emerges from these circumstances will find few opportunities to escape a life of poverty. It’s a vicious circle that is shattering American communities.

The folks I grew up with deserve better than the choices either party has offered in the past couple of elections. Liberals promise a big, intrusive, and all-providing government that sucks the life and faith out of families and communities. But conservatives give the impression that they are unconcerned about the millions of hurting and vulnerable Americans. No wonder so many people stayed home on Election Day 2012. Our country needs opportunities for all, not just the financiers on the East Coast or the high-tech tycoons on the West. And that means focusing on what will strengthen the families and communities of ordinary Americans who want to work.

When I ran for president, I noticed that what stuck in people’s minds was not my policy pronouncements but images (not the ones that political consultants contrive, but something as simple as a sweater vest) and stories like the one I told the night I won the Iowa caucuses. I recalled kneeling next to my grandfather’s coffin, where all I could do was look at his hands. They were the powerful hands of a miner, thick and scarred. It struck me then that those hands dug freedom for me.

In the last few years, a lot of us have realized that we can lose that freedom. In fact, we may be perilously close to losing it right now. America should be a land of opportunity and its people full of hope. But I saw firsthand the hopelessness in the eyes of thousands of our countrymen. Who is going to help them? There are things we can do, but we’ll need the resolve of heroes. This country, thank God, has never been short of heroes.

In the chapters to follow, I’ll explore what went wrong and what killed opportunity for so many Americans. And I’ll share my ideas about how we can rebuild this economy and our communities. If running for president teaches you anything, it’s that no one has all the answers. But there’s one thing I know with absolute certainty—we Americans have always met the challenges that history has thrown at us, and we can meet them again.

CHAPTER TWO

RESTORING THE AMERICAN DREAM FOR WORKERS

All of us have a picture in our head of what the American Dream looks like. It probably includes owning your own home, having a family and a good job, being active in your church and community, sending your kids off to college or technical school, and then retiring comfortably and spoiling your grandkids. Whatever variation each of us has of this vision, the American Dream is always the dream of a better life for us and for our children, of leaving our little corner of the world better than we found it.

If you ask people what trait is most characteristically American, many of them will answer “rugged individualism.” It’s true that this country’s respect for the dignity and freedom of the individual is unique in the history of the world, and it’s at the heart of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Blue Collar Conservatives Really Did Build It

- Chapter 2: Restoring the American Dream for Workers

- Chapter 3: A GOP That Stands Up for Everyone

- Chapter 4: Holes in the Boat

- Chapter 5: Renewing the Pursuit of Happiness

- Chapter 6: Government Cannot Read You a Bedtime Story

- Chapter 7: Replace Obamacare Before It’s Too Late

- Chapter 8: Innovating and Personalizing Education

- Chapter 9: Giving the American Worker a Fighting Chance

- Chapter 10: Raising Hope instead of Taxes

- Chapter 11: Believing in America’s Future

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index