- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Other Stories

About this book

Scurry down the rabbit hole and step through the looking glass with this compilation of works from Lewis Carroll. Don’t be late--it’s a very important date!

Witty, whimsical, and often nonsensical, the fiction of Lewis Carroll has been popular with both children and adults for over 150 years. Canterbury Classics's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland takes readers on a trip down the rabbit hole in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where height is dynamic, animals talk, and the best solutions to drying off are a dry lecture on William the Conqueror and a Caucus Race in which everyone runs in circles and there is no clear winner.

Through the Looking Glass begins the adventure anew when Alice steps through a mirror into another magical world where she can instantly be made queen if she can only get to the other side of the colossal chessboard.

Complete with the original drawings by John Tenniel, this edition is a steal for new readers and Carroll fans alike.

Witty, whimsical, and often nonsensical, the fiction of Lewis Carroll has been popular with both children and adults for over 150 years. Canterbury Classics's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland takes readers on a trip down the rabbit hole in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where height is dynamic, animals talk, and the best solutions to drying off are a dry lecture on William the Conqueror and a Caucus Race in which everyone runs in circles and there is no clear winner.

Through the Looking Glass begins the adventure anew when Alice steps through a mirror into another magical world where she can instantly be made queen if she can only get to the other side of the colossal chessboard.

Complete with the original drawings by John Tenniel, this edition is a steal for new readers and Carroll fans alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Other Stories by Lewis Carroll,John Tenniel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Classics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SYLVIE AND BRUNO CONCLUDED

Dreams, that elude the Maker’s frenzied grasp—

Hands, stark and still, on a dead Mother’s breast,

Which nevermore shall render clasp for clasp,

Or deftly soothe a weeping Child to rest—

In suchlike forms me listeth to portray

My Tale, here ended. Thou delicious Fay—

The guardian of a Sprite that lives to tease thee—

Loving in earnest, chiding but in play

The merry mocking Bruno! Who, that sees thee,

Can fail to love thee, Darling, even as I?

My sweetest Sylvie we must say “Good-bye!”

PREFACE

Let me here express my sincere gratitude to the many reviewers who have noticed, whether favourably or unfavourably, the previous volume. Their unfavourable remarks were, most probably, well-deserved; the favourable ones less probably so. Both kinds have no doubt served to make the book known, and have helped the reading public to form their opinions of it. Let me also here assure them that it is not from any want of respect for their criticisms, that I have carefully forborne from reading any of them. I am strongly of opinion that an author had far better not read any reviews of his books: the unfavourable ones are almost certain to make him cross, and the favourable ones conceited; and neither of these results is desirable.

Criticisms have, however, reached me from private sources, to some of which I propose to offer a reply.

One such critic complains that Arthur’s strictures, on sermons and on choristers, are too severe. Let me say, in reply, that I do not hold myself responsible for any of the opinions expressed by the characters in my book. They are simply opinions which, it seemed to me, might probably be held by the persons into whose mouths I put them, and which were worth consideration.

Other critics have objected to certain innovations in spelling, such as “ca’n’t,” “wo’n’t,” “traveler.” In reply, I can only plead my firm conviction that the popular usage is wrong. As to “ca’n’t,” it will not be disputed that, in all other words ending in “n’t,” these letters are an abbreviation of “not;” and it is surely absurd to suppose that, in this solitary instance, “not” is represented by “ ’t!” In fact “can’t” is the proper abbreviation for “can it,” just as “is’t” is for “is it.” Again, in “wo’n’t,” the first apostrophe is needed, because the word “would” is here abridged into “wo”: but I hold it proper to spell “don’t” with only one apostrophe, because the word “do” is here complete. As to such words as “traveler,” I hold the correct principle to be, to double the consonant when the accent falls on that syllable; otherwise to leave it single. This rule is observed in most cases (e.g., we double the “r” in “preferred,” but leave it single in “offered”), so that I am only extending, to other cases, an existing rule. I admit, however, that I do not spell “parallel,” as the rule would have it; but here we are constrained, by the etymology, to insert the double “l.”

In the Preface to Vol. I. were two puzzles, on which my readers might exercise their ingenuity. One was, to detect the 2 lines of “padding,” which I had found it necessary to supply in the passage on p. 181. They are the 31st and the 32nd lines of p. 181. The other puzzle was, to determine which (if any) of the 8 stanzas of the Gardener’s Song (see pp. 190, 194, 196, 199, 203, 206, 223, 225) were adapted to the context, and which (if any) had the context adapted to them. The last of them is the only one that was adapted to the context, the “Garden-Door that opened with a key” having been substituted for some creature (a Cormorant, I think) “that nestled in a tree.” At pp. 194, 203, and 223, the context was adapted to the stanza. At p. 199, neither stanza nor context was altered: the connection between them was simply a piece of good luck.

In the Preface to Vol. I., at pp. 164, I gave an account of the making-up of the story of Sylvie and Bruno. A few more details may perhaps be acceptable to my Readers.

It was in 1873, as I now believe, that the idea first occurred to me that a little fairytale (written, in 1867, for Aunt Judy’s Magazine, under the title “Bruno’s Revenge”) might serve as the nucleus of a longer story. This I surmise, from having found the original draft of the last paragraph of Vol. II., dated 1873. So that this paragraph has been waiting 20 years for its chance of emerging into print—more than twice the period so cautiously recommended by Horace for “repressing” one’s literary efforts!

It was in February, 1885, that I entered into negotiations, with Mr. Harry Furniss, for illustrating the book. Most of the substance of both volumes was then in existence in manuscript: and my original intention was to publish the whole story at once. In September, 1885, I received from Mr. Furniss the first set of drawings—the four which illustrate “Peter and Paul”: in November, 1886, I received the second set—the three which illustrate the Professor’s song about the “little man” who had “a little gun”: and in January, 1887, I received the third set—the four which illustrate the “Pig-Tale.”

So we went on, illustrating first one bit of the story, and then another, without any idea of sequence. And it was not till March, 1889, that, having calculated the number of pages the story would occupy, I decided on dividing it into two portions, and publishing it half at a time. This necessitated the writing of a sort of conclusion for the first volume: and most of my Readers, I fancy, regarded this as the actual conclusion, when that volume appeared in December, 1889. At any rate, among all the letters I received about it, there was only one which expressed any suspicion that it was not a final conclusion. This letter was from a child. She wrote “we were so glad, when we came to the end of the book, to find that there was no ending-up, for that shows us that you are going to write a sequel.”

It may interest some of my Readers to know the theory on which this story is constructed. It is an attempt to show what might possibly happen, supposing that Fairies really existed; and that they were sometimes visible to us, and we to them; and that they were sometimes able to assume human form: and supposing, also, that human beings might sometimes become conscious of what goes on in the Fairy world—by actual transference of their immaterial essence, such as we meet with in “Esoteric Buddhism.”

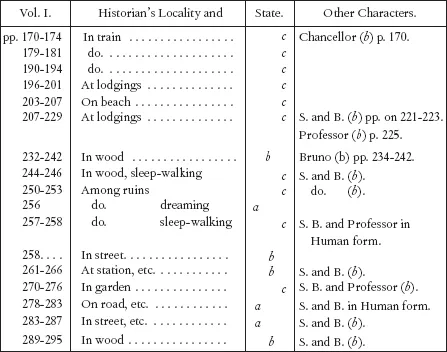

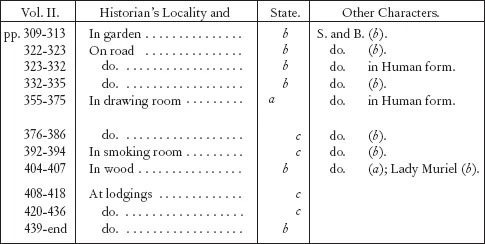

I have supposed a Human being to be capable of various psychical states, with varying degrees of consciousness, as follows:

(a) the ordinary state, with no consciousness of the presence of Fairies;

(b) the “eerie” state, in which, while conscious of actual surroundings, he is also conscious of the presence of Fairies;

(c) a form of trance, in which, while unconscious of actual surroundings, and apparently asleep, he (i.e., his immaterial essence) migrates to other scenes, in the actual world, or in Fairyland, and is conscious of the presence of Fairies.

I have also supposed a Fairy to be capable of migrating from Fairyland into the actual world, and of assuming, at pleasure, a Human form; and also to be capable of various psychical states, viz.

(a) the ordinary state, with no consciousness of the presence of Human beings;

(b) a sort of “eerie” state, in which he is conscious, if in the actual world, of the presence of actual Human beings; if in Fairyland, of the presence of the immaterial essences of Human beings.

I will here tabulate the passages, in both volumes, where abnormal states occur.

In the Preface to Vol. I., at p. 164., I gave an account of the origination of some of the ideas embodied in the book. A few more such details may perhaps interest my Readers:

I. p. 236. The very peculiar use, here made of a dead mouse, comes from real life. I once found two very small boys, in a garden, playing a microscopic game of “Single-Wicket.” The bat was, I think, about the size of a tablespoon; and the utmost distance attained by the ball, in its most daring flights, was some 4 or 5 yards. The exact length was of course a matter of supreme importance; and it was always carefully measured out (the batsman and the bowler amicably sharing the toil) with a dead mouse!

I. p. 255. The two quasi-mathematical Axioms, quoted by Arthur at p. 255 of Vol. I. (“Things that are greater than the same are greater than one another,” and “All angles are equal”) were actually enunciated, in all seriousness, by undergraduates at a University situated not 100 miles from Ely.

II. p. 310. Bruno’s remark (“I can, if I like, etc.”) was actually made by a little boy.

II. p. 311. So also was his remark (“I knows what it doosn’t spell”). And his remark (“I just twiddled my eyes, etc.”) I heard from the lips of a little girl, who had just solved a puzzle I had set her.

II. p. 325. Bruno’s soliloquy (“For its father, etc.”) was actually spoken by a little girl, looking out of the window of a railway-carriage.

II. p. 351. The remark, made by a guest at the dinner party, when asking for a dish of fruit (“I’ve been wishing for them, etc.”) I heard made by the great Poet-Laureate, whose loss the whole reading-world has so lately had to deplore.

II. p. 359. Bruno’s speech, on the subject of the age of “Mein Herr,” embodies the reply of a little girl to the question “Is your grandmother an old lady?” “I don’t know if she’s an old lady,” said this cautious young person; “she’s eighty-three.”

II. p. 372. The speech about “Obstruction” is no mere creature of my imagination! It is copied verbatim from the columns of the Standard, and was spoken by Sir William Harcourt, who was, at the time, a member of the “Opposition,” at the “National Liberal Club,” on July the 16th, 1890.

II. p. 414. The Professor’s remark, about a dog’s tail, that “it doesn’t bite at that end,” was actually made by a child, when warned of the danger he was incurring by pulling the dog’s tail.

II. p. 427–428. The dialogue between Sylvie and Bruno, is a verbatim report (merely substituting “cake” for “penny”) of a dialogue overheard between two children.

One story in this volume—“Bruno’s Picnic”—I can vouch for as suitable for telling to children, having tested it again and again; and, whether my audience has been a dozen little girls in a village school, or some thirty or forty in a London drawing room, or a hundred in a High School, I have always found them earnestly attentive, and keenly appreciative of such fun as the story supplied.

May I take this opportunity of calling attention to what I flatter ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Through the Looking-Glass

- Sylvie and Bruno

- Sylvie and Bruno Concluded

- A Tangled Tale

- Novelty & Romancement

- Photographer’s Day Out

- The Legend of Scotland

- Wilhelm Von Schmitz