- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

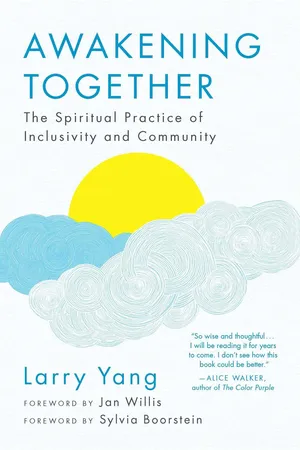

About this book

“Awakening Together combines the intimately personal, the Buddhist and universal into a loving, courageous, important work that will benefit all who read it. For anyone who longs to collaborate and create a just and inclusive community, Larry provides a brilliant guidebook.”

—Jack Kornfield, author of A Path With Heart

How can we connect our personal spiritual journeys with the larger course of our shared human experience? How do we compassionately and wisely navigate belonging and exclusion in our own hearts? And how can we embrace diverse identities and experiences within our spiritual communities, building sanghas that make good on the promise of liberation for everyone?

If you aren’t sure how to start this work, Awakening Together is for you. If you’ve begun but aren’t sure what the next steps are, this book is for you. If you’re already engaged in this work, this book will remind you none of us do this work alone. Whether you find yourself at the center or at the margins of your community, whether you’re a community member or a community leader, this book is for you.

—Jack Kornfield, author of A Path With Heart

How can we connect our personal spiritual journeys with the larger course of our shared human experience? How do we compassionately and wisely navigate belonging and exclusion in our own hearts? And how can we embrace diverse identities and experiences within our spiritual communities, building sanghas that make good on the promise of liberation for everyone?

If you aren’t sure how to start this work, Awakening Together is for you. If you’ve begun but aren’t sure what the next steps are, this book is for you. If you’re already engaged in this work, this book will remind you none of us do this work alone. Whether you find yourself at the center or at the margins of your community, whether you’re a community member or a community leader, this book is for you.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Awakening Together by Larry Yang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Buddhism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Suffering into Freedom

OVER THE YEARS I have come to a deep commitment to and faith in the teachings of the Buddha. These are teachings that have fed and nurtured my spiritual needs and development as a human being. In this life that has been given me, the Dharma of the Buddha has been transformative.

It might be an easy assumption to make (or maybe a stereotype) that an Asian American, born to rather traditional parents who emigrated from the outskirts of Shanghai in northern China, would gravitate to a Buddhist spiritual practice. Indeed, my mother was raised in a household whose members were devotionally Buddhist, and my father, who was a Confucian Taoist, was not unfamiliar with Buddhist temples and practice. However, the cultural equation of connecting my own Asian heritage to the Buddhist tradition (or any spiritual tradition at all, for that matter) was not so direct or simple.

Much of my early childhood was spent in Levittown, Pennsylvania — the epitome of those postwar suburban developments of affordable, homogenous homes of the late 1950s and early 1960s, the ones that Pete Seeger sang about. For me at the time, though, Levittown did not seem to have the monotonous, uninspired uniformity Seeger’s lyrics evoked. After all, it was the world of my childhood. And as for most children, even this most mundane environment was exciting and interesting.

Levittown was a place with a hill for shooting down on a bike whose weight and design would be embarrassing in today’s sophisticated choices of racing, recumbent, mountain, touring, and BMX models: a “Schwinn-built” American Flyer. And in bright maroon, it was the coolest thing to show off on as a seven- or eight-year-old.

Levittown was a place with a creek — though English being my second language, I remember having trouble with whether the word should be pronounced “creek” or “crick.” That creek provided an illusion of wilderness for a young, wide-eyed, mock scientist who dissected bugs, poked at frogs, and tried to catch minnows with awkward little fingers. My scientific methodology was undeveloped, but the intention of curiosity was already well into formation.

It was in Levittown on November 22, 1963, that I remember running up the front lawn (it wasn’t that big, but to my short, stubby legs it seemed like a track field) telling my mother that President Kennedy had been shot. My mom had not been listening to the news that day, but I had been listening to the radio in the carpool coming home from my Quaker elementary school. I knew that it was an event that was really important and really sad. We sat in front of our RCA black-and-white TV set transfixed by the unfolding tragedy along with millions of other Americans that day.

And it was in Levittown where I had my first experience of racism.

I can remember running up the same lawn with different news for my mom. Instead of bursting inside without a care in the world, I carefully opened the screen door. I turned the brass knob of a front door painted as red as my Radio Flyer wagon, and let the screen door gently close without the typical crash that followed me.

I guess I didn’t look too happy: my mom came up and knelt so that her face was at the same level as mine. We weren’t a physically affectionate family; that hasn’t been my experience of the Asian or Chinese way of doing things. Love and other emotions were shown through behavior, rather than gesture or verbal expression. But this time, she reached out to my shoulder, “What’s the matter, Larry?”

I almost didn’t want to answer.

“Ma, what does chink mean?”

My mother’s prolonged pause reinforced what I already knew — that this, like the news of Kennedy’s assassination, was a life experience that was really sad. It was a lightning bolt that illuminated for me how people perceive each other and treat each other badly based upon how different they seem. I didn’t know the words race, culture, or ethnicity, but I could still feel the nausea and tension in my little body. It was one of those aha moments that children can have, and it came in a flash.

It wasn’t an experience of understanding — as a kid, I couldn’t understand what was happening — but I did recognize that it was something important. It simply was what it was: a moment of awareness — awareness of suffering in my life. And that is what my mother reflected back to me.

She said after a moment, “Sometimes that is just the way things are in the world.”

It was an unsatisfactory response to the racism of which I was just beginning to become conscious. But it was also the best she could offer at the time in a world rife with the cultural complexities of post-McCarthyism and the Vietnam War. I was too young to grasp anything beyond the immediate experience of my own suffering and pain.

Much later in life I read a passage in James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son that resonated very deeply with me. At the end of his description of the experience of being refused service at a diner because they didn’t serve “Negroes” there, Baldwin writes, “And I felt, like a physical sensation, a click at the nape of my neck as though some interior string connecting my head to my body had been cut.”

In hindsight of my own string being cut, I appreciate that I recognized some part of my experience as a moment when cultures intersect. I was fast-tracking out of childhood, and I was losing my innocence.

My childhood home was a place where my everyday companions and best friends were the kids of our immediate neighbors on both sides of our house. A pair of brothers, Steven and Burton, lived to the left of my house, and another pair of brothers, Buddy and Randy, lived to the right. There was about three years’ difference between the two pairs, enough at that age to completely separate them into different interests and different preadolescent worlds. I was exactly in the middle age-wise, allowing me to hang out with either pair of boys.

It was a confusingly tender time for me — the naive simplicity of rolling down freshly mowed lawns, hiding from grownups in the hedges, and plotting not to be seen by the “nerdy” girls — because I was hiding one more secret from everyone else, a secret kept hidden in the safe recesses of my own mind where I thought I could control and manage it. My secret was that I was a boy who felt the need for more connection and relationship with other boys.

As with the racism I encountered, I didn’t even have a word for this feeling, much less comprehend terms like sexual orientation, homosexuality, or gay. I just knew that I felt even more different from other kids around me, beyond my skin color, the shape of my eyes, and the details of my cultural background. I felt different from those whom I felt I belonged to — my family. And I knew almost as soon as I had the feelings, whatever it was called, that people did not treat it with acceptance, kindness, or love. The cultural worlds I found myself torn between began to expand in number.

In the balance of things, for me life usually felt more painful than not back then. There was tremendous pain in not knowing where I belonged and not feeling that I belonged anywhere with anyone. I imagine some version of this arises in many people during adolescence, regardless of culture, race, or sexual orientation, but those issues simply heightened the angst of a young person who had yet to develop any life skills that would be of guidance or support. And it created in me a tremendous desire to get rid of the pain and suffering. I became determined to become a person who I was not.

I lost interest in my language of origin, my cultural heritage, and some of the deep sources of my identity — even in my childhood friends who were Asian. Family history and lineage became quaint stories that I tolerated to humor my parents and relatives over holidays, but they did not concern me in my “real life” in the “real American” white world.

I measured myself against the achievements of others who looked as if they belonged to the American mainstream and who seemed successful in the dominant culture. I wanted to assimilate without condition — to be accepted by them. The feelings of unmitigated separation produced a craving for connection, a desperation to belong. In a determined exertion of willpower as I came of age, I remember having the fixed conviction that if it is this difficult to be a racial minority in this world, there is no way that I will be gay — thereby adding another padlock to an already hidden closet door.

But the locks wouldn’t hold; the closet and the closet door were rotting from the inside out.

I was deeply unhappy even though I had no idea why. My attempts at assimilation into a white, heterosexual culture took me further away from my identity as a gay Chinese man. This gap between realities became deeper as the internal dissonance lengthened in duration. The void was filled repeatedly with excessive amounts of alcohol, drugs, caffeine, and nicotine — anything at all but the real feelings emerging from my experience with my life.

When I encountered the Buddha’s teachings, I was a deeply tortured soul.

Though I might have had many elements in my life (including, at the time, a partner) that might have looked good from the outside, inside my psyche was ruptured. Even during my recovery from substance abuse, the pain did not abate.

When the Dharma entered my life, I realized that my life was deeply unhappy because I was turning away from who I was. I was trying to be who I was not. In turning toward all of the aspects of myself that I had denied and repressed earlier, I was beginning my path of mindfulness, of being aware of who is living this human life as “me.”

I turned toward the familiar stranger within myself. I turned my attention to the pieces of my personality and history, my successes and failures, my dreams and depressions, I was afraid to get to know, much less become intimate with. I turned toward my sexual orientation and identity and my racial and cultural background.

This path of Dharma was the beginning of the healing process, of recovering who I saw myself to be in this world and who I could become. From that deeply tortured soul, this path has shown me greater and greater amounts of ease, peacefulness, and — dare I say — freedom. What more can I ask for? This path of Dharma has shown me where to start, where to continue, and how the path has no end to possibilities of freedom — even amid the myriad forms of suffering.

2

Finding a Spiritual Path

WE ARE all seekers.

We are seekers regardless of which spiritual tradition we affiliate with. We are seekers even if we do not espouse any religious faith at all. We all search for meaningful experiences, satisfying objects, compatible people, useful knowledge, fulfilling activities, well-being — and more. Seeking is part of our humanity. When we seek, inquire, and explore, we open up to our own life and to the world. This openness is a tender place for both our minds and hearts. From this tender place, we look for things that we hope will create more happiness and contentment for ourselves.

This begins so early in our precious lives.

We are on this earth for such a short period of time. It’s no wonder that moments after we enter this life we start looking, learning, and seeking that which will make the best of this life. Even before we have any words to describe it, there is the message implicit in a baby’s cry of “What will satisfy me?” “How do I get my mother’s milk?” “What is that flashing color?” “Look at this thing that is a ‘foot.’ I don’t even know the word foot, but look at what it can do!”

As we are parented, cared for, and nurtured, we reach further into the world, recognizing the pleasant sensations of a pillow or blanket or favorite stuffed animal, and, later, begin to wonder “why?”

Why is the sky blue?

I remember lying on the grass in the warmth of a sunny day — daydreaming or maybe day-wondering — simply staring into the sky with amazement and openness. I was content to watch the clouds, looking on as scenes and objects and beings appeared, dissolved, and reappeared amid the ever-shifting curves and wisps of white billowing puffs. Those early memories are the first time I had a sense of presence, of peace — even if it was fleeting, or not fully recognized by me in that moment. We all dream as children.

In the Buddhist tradition, there is a story of a prepubescent boy having a similar childhood experience. Even though the story is specifically set in a distant culture, in a distant time more than 2,500 years ago, in what is now northeastern India and southern Nepal, I feel a connection to the tenderness of this child — and indeed any child who is seeking. That boy was named Siddhartha and was the son of a local king. At the age of seven, Siddhartha attended a celebratory festival and party over which his father was presiding. His attendants (whom we would perhaps now call his daycare providers) got attracted to the party themselves and left the youth to his own resources in a vast field under a great tree.

As with many cultures and human traditions, the tree has tremendous significance in what it represents. Even in those times of ancient India, one association was the tree of life — the feet of which are anchored with roots deep into the earth with a summit reaching into the heavens in all directions. This image is embedded in our collective psyche, regardless of whether our cultural origins are from Asia, Africa, the Americas, or Europe. The Great Tree encompasses and shelters all experiences in our life, just like it was protecting the youthful Siddhartha. Indeed, that tree echoes Siddhartha’s birth into the world beneath the boughs of another ancient tree and presages the Buddha’s enlightenment sitting underneath the spreading limbs of the great bodhi tree.

As the boy sat in the field, a sense of stillness and peace cascaded into his awareness. He wondered, “As I am sitting in the shade of this tree, removed from the distractions of senses and difficult states of mind and heart, allowing the mind to settle into a natural joyousness, can this be the path that I am searching for?”

Whether we are totally conscious of it or not, our spiritual lives begin when we are children.

Our spirituality has always been with us, and the seeker has always been present.

I grew up in a family that had immigrated to the United States during difficult global and cultural times, encompassing situations not unlike the challenges facing many culturally displaced peoples today. My parents emigrated from China just at the ending of World War II and the resurgenc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Jan Willis

- Foreword by Sylvia Boorstein

- Preface: Now More Than Ever

- Acknowledgments

- 1. From Suffering into Freedom

- 2. Finding a Spiritual Path

- 3. This Precious Life

- 4. Nobility of Truth

- 5. Awakening Together

- 6. Refuge in a Multicultural World

- 7. Beautiful and Beloved Communities

- 8. The Precious Experience of Belonging

- 9. A Place to Call Home

- 10. The Beauty of Transformation

- 11. Aware Within and Without

- 12. Heart and Mind, Together

- 13. Transformation of the Heart

- 14. Moving Toward Freedom

- 15. Consciously Creating Community

- 16. Breaking Together

- 17. Supported on Each Other’s Shoulders

- 18. Manifesting Diverse Spiritual Leadership

- 19. Integrity: A Challenging Practice in Challenging Times

- Epilogue: A Long and Winding Road

- Appendix 1: Steps to Take Now

- Appendix 2: Learning Points from East Bay Meditation Center

- Appendix 3: East Bay Meditation Center’s Agreements for Multicultural Interactions

- Appendix 4: History of Diversity-Related Events in the Western Insight Meditation Community

- Index

- About the Author

- Copyright