- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

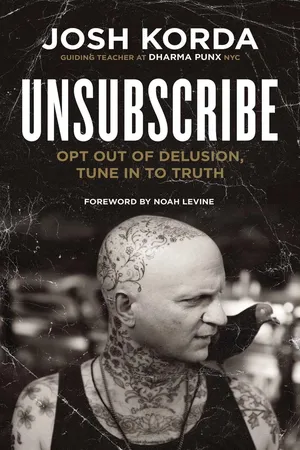

A three-step guide to recovery from addiction to consumerism, self-deception, and life as you thought it had to be.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Josh Korda left his high-powered advertising job—and a life of drug and alcohol addiction—to find a more satisfying way to live. In Unsubscribe, he shares his three-step guide to recovery from addiction to consumerism, self-deception, and life as you thought it had to be.

(1) Reprioritize your goals, away from a materialist vocation toward a fulfilling avocation

(2) Understand yourself and your emotional needs

(3) Connect authentically with others, leading to secure relationships and true community.

Revolutionary, compassionate, and filled with wonderfully practical exercises, Josh will help you lead a more authentic, more fulfilling life.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Josh Korda left his high-powered advertising job—and a life of drug and alcohol addiction—to find a more satisfying way to live. In Unsubscribe, he shares his three-step guide to recovery from addiction to consumerism, self-deception, and life as you thought it had to be.

(1) Reprioritize your goals, away from a materialist vocation toward a fulfilling avocation

(2) Understand yourself and your emotional needs

(3) Connect authentically with others, leading to secure relationships and true community.

Revolutionary, compassionate, and filled with wonderfully practical exercises, Josh will help you lead a more authentic, more fulfilling life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unsubscribe by Josh Korda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Buddhism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Emotional Reasoning: Understanding Yourself

6. | SELF-INTEGRATION THROUGH MINDFULNESS |

Mindfulness of the Body and Emotions Leads to Self-Integration and Away from Self-Sabotage

IN LIFE we rely heavily on what could be called the “representational’” capabilities of the mind to assist us in making all our important decisions. Let’s investigate how this works.

Occasionally I receive emails describing interesting teaching opportunities: “Josh, we would love you to come teach at our new Dharma center!” The message describes the center, its size, community, location, which time slots are available, how much of my travel expenses they could cover, and any number of other details. When it’s time for me to decide whether or not to pursue the opportunity, I might feel inclined to “figure out what to do”: switch on the neural circuitry that allows me to visualize a sequence of images involving traveling and teaching at a place I actually haven’t seen or visited. In essence I’m projecting what a future experience might entail, based on assumptions, cobbled-together images from previous experiences, imagination, expectations, and so on.

Another example: When I’m burdened by financial or interpersonal obligations, undetermined schedules, missed appointments, and so forth, my first inclination is to create an array of speculative visual images and thoughts, little movies that portray “ways out” of my present dilemmas. One movie shows me hopping on a plane to southeast Asia — moving to a remote tropical beach where I envision life’s dramas left behind, all tension resolved. I shrug off such quick fixes: they’re too escapist, and unlikely, given all the ties that bind me to Brooklyn and my spiritual community. Next I may imagine telling off those individuals I believe are getting in my way. Once again I decline this solution, perhaps from an unhealthy tendency to avoid conflicts, or perhaps from a wiser realization that these individuals aren’t responsible for the tension I’m feeling, that my discomfort with unresolved issues lies at the heart of my present suffering.

What I’m doing in these examples is representing the world in my head. I’m painting an internal version of the world, so that I can play out possibilities and work through different possible scenarios, all to reach a decision.

It’s easy to be unaware of how much we rely on abstract representations of the external universe to make choices and decisions. And representations help us with more than just choices; abstract thought allows us to replay life’s confusing or overwhelming events over and over, so that we can find some form of coherence or meaning that wasn’t originally apparent. After breakups, conflicts, stressful encounters, and disappointing news we replay the experience, trying to figure out what it all meant, what went wrong, how we can avoid bad news in the future.

What we generally fail to realize is that representational thought is often largely the product of the left hemisphere of our brains, which prioritizes accomplishment, accumulation, and manipulating the world to our advantage, at the expense of the right hemisphere’s needs, which emphasize maintaining secure interpersonal attachments and personal safety.

The analytical, planning, and organizing circuits also have another tendency that should be noted as well: In re-presenting the world, our thoughts tend to reduce new experiences into familiar concepts and beliefs: what the Buddha called sanna, or preexisting perceptions of the world. In the Pali Canon, sanna-vipallasa, which roughly translates as “distortions of perception,” refers to the degree to which the world is misperceived and altered as we transform actual, sensory-rich experience into disembodied ideas for our thoughts to manipulate. For example, if I view any possibility to teach as beneficial to building a reputation as a Dharma teacher, then the sanna associated with teaching will lead to positive visualizations of any opportunity. I’ll overlook whether or not the occasion is, for example, ethically sound (I’ve received countless offers to teach at large corporations, which I invariably decline). Every time I rely on representational thought, I’m flattening the world into simplistic personal associations, which primarily consist of old distorted ideas. So much for “thinking our way out” of situations.

The more we try to problem solve by relying on narrative thought, the more we’re likely to prioritize financial gain, awards and titles, and achievements over our needs for love, community membership, and empathetic connection with loved ones.

A study by Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert called “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind” noted that we spend almost half of our lives thinking about things other than what we’re doing; instead we’re creating alternative realities in our minds to help us worry, fantasize, and remember. The study additionally demonstrated that such speculative/representative cognition generally tends to leave us stressed and unhappy. Perhaps this is because when we’re not present, we quickly lose awareness of our feelings and emotions; many of our trains of thought take us nowhere good.

But neither you nor I have to rely on the representational circuits as a primary tool for making decisions and navigating through life; the best way to “process what it means” isn’t necessarily to imagine the past or the future. The circuits that translate our rich, embodied experience into words and ideas are only a small part of our cognitive capabilities. We love the idea that our thought is at the epicenter of the mind, controlling our behaviors and impulses, but, as the Buddha noted in his causal chain of suffering, thought arrives after feelings and impulses, both of which we’re generally quite unaware.

Furthermore, a lot of the suffering in our lives comes from trying to think our way through everything while disregarding the important information our emotions present. While we may be tempted to believe that logic, planning, and organization, in conjunction with meditation and spiritual reflection, should be enough to navigate through life, our emotions aren’t useless. They are important messages, sent via physical impulses, felt urges, body states, and nonverbal cues from the unconscious mind — which prioritizes security and connection over ambition and achievement.

If I could summarize my work as a Buddhist teacher and mentor into a single unifying goal or theme, it would be providing people with the many tools of the Dharma that allow us to translate and integrate the emotional mind into our conscious, ambitious life agendas. In every situation in life we are of at least two minds: one that consciously interprets events through language and ambitious narratives, reviewing how each event will fit into our plans for the future, and one that is unconscious, deciphering experience in terms of our connection to the pack. In order to pay proper attention to the latter, we must develop awareness of all the nonverbal elements of our internal experience — such as our breath, gut feelings, and moods — so that we may consider the needs they’re expressing: never-ending hopes for love, connection, emotional support.

When it comes time to decide whether or not to accept a teaching opportunity, in order to integrate both halves of my mind, I may turn my attention away from narrative, representational thought, focusing my attention instead on the actual experience of stress itself: the uncomfortable breathing comprised of fast inhalations and shallow, incomplete exhalations; the sensations of muscles in the stomach and shoulders contracting; my jaw locking tight and my forehead muscles pulling taut; my attention jumping about from one idea to another. And so I let go of addressing life as if it’s a set of problems to be solved, and address what’s actually present. I’ve moved from a “top-down” cognitive approach to resolving life’s suspense or uncertainties (thinking my way out of challenges) to a “bottom-up” process (becoming aware of the physical and mental states that constitute the actual experience of worry, boredom, discomfort, and so on). I will likewise investigate what lies beneath neutral and positive experiences as well.

This is a systemic approach to refocusing the mind away from external concerns (which can feel insurmountable) toward an internal awareness of the agitation itself. After all, it’s far easier to control one’s breath and relax one’s muscles than it is to control other people, no?

It’s important to remember, however, that such mindfulness is not a form of acquiescence or resignation. It doesn’t mean we agree with the conditions around us, that we won’t quit jobs we hate, that we concede that radical change cannot happen in our lives. Indeed, I’ve found that deeply investigating an experience, even the profoundly mundane and meaningless, is to pay attention to how I really feel while I’m there, in the salt mines, wasting away my precious minutes and hours — and this shows me what I need to do, to change, to get out.

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness and the Parts of Your Brain

If we are to practice such a fundamental cognitive shift, from external vigilance to internal awareness, it helps if we investigate the different systems of the mind in a succession of stages. Many of the processes of our minds are generally spurned as uninteresting, left outside the spotlight of conscious attention, even though they have profound influence over our choices, behaviors, and the very shapes of our lives.

So let’s start with what keeps us breathing, thermally regulated, and digesting food, all while we attend to headier, more elevated concerns: the brainstem and hindbrain, which are the oldest parts of the brain. They organize our core movements; thanks to these regions we can breathe without oversight.

The breath is a very important tool for keeping a steady stream of oxygen in the body, but it’s also a way to develop peace and to maintain calm. In fact, many of the aims that bring many of us to spiritual practice can be addressed by bringing our attention to how we are breathing.

Our brains are set to a needlessly high default level of threat detection, even though we as a species have never been safer, due to advances in medicine and efficient storage of food supplies, and perhaps the systemic eradication of our predators. Evolution, however, has not kept up the pace, and so we’re wired for survival the same way we were tens of thousands of years ago, when the world was a significantly more dangerous place to survive. So our stress levels are way too high, considering that most of us will probably not be chased and consumed by predators. Chronic stress can lead to a variety of health problems: impaired immune function, digestive issues, diabetes, etc.

When we bring our attention to the breath and gradually lengthen the exhalations, we essentially lower our threat sensitivity level to a far less vigilant state, which leads to long-term health benefits. We lower our heart rates, relax, and make eye contact and attune with others; we increase our ability to focus and maintain calmness and decrease anxiety.

Thus, even though we may not consciously notice them, the oldest systems of the brain profoundly influence our current experience. And appropriately enough, the first foundation of mindfulness is awareness of the body, for which the breath is a good entryway.

Once we have become familiar with the quality of our breath, the Buddha has us shift awareness to the body; as described in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness Sutta, we become aware of the sensations associated with our present state, whether we are “walking about, standing and looking around, bending down or extending our limbs in any manner, while eating, drinking, chewing and tasting, during urination and defecation, talking, and remaining silent . . .” Bodily experience provides a primary channel for self-care. In paying attention to the sensations of body — Are my shoulders relaxed or tightened? Are my palms relaxed or gripping? Am I looking straight ahead or is my head habitually tilted downward? — it becomes possible to address functions of the brain that maintain psychological disorders. Therapies that focus on a patient’s physical sensations, for instance, have proven very effective at treating PTSD. Once again, we are working from the bottom up rather than top-down.

The second foundation of mindfulness is mindfulness of feelings and sensations.

Strong physical sensations known as gut feelings or somatic markers are often signals from the right hemisphere of our brains, which is exceedingly connected to the body and tends to express itself physically more than the left hemisphere does. The right hemisphere is the seat of our emotions and governs how we behave in our interpersonal affairs; the left is the realm of abstract, representational thought. The activity of the right is often perceptible to us if we note our bodily sensations. For instance, we can pick up on the presence of an underlying emotional state by noting the muscle groups in the front of the body; there is a cluster of nerves that connects the brain stem to the muscles of the face, throat, heart, and abdominal region, which is why we can physically experience separa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Practices

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- I. Death Benefits: Getting Our Priorities Straight

- II. Emotional Reasoning: Understanding Yourself

- III. Alone Together: Connecting with Others

- IV. Opting In for Liberation

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Copyright