eBook - ePub

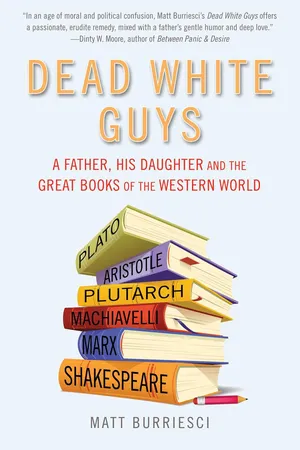

Dead White Guys

A Father, His Daughter and the Great Books of the Western World

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Dead White Guys is a timely defense of the great books, arriving in the middle of a national debate about the fate of these books in high schools and universities around the country. Burriesci shows how the great books can enrich our lives as individuals, as citizens, and in our careers. Extending the argument first made by Anna Quinndlen's on the act of reading itself, How Reading Changed My Life," ("It is like the rubbing of two sticks together to make a fire, the act of reading, an improbable pedestrian task that leads to heat and light,) Burriesci reminds us all of the enormous impact reading has on our lives. After his daughter was born prematurely in 2010, Burriesci set out to write a book about 26 Great Books, from Plato to Karl Marx, and how their lessons have applied to his life. As someone who has spent a long and successful career advocating for great literature, Burriesci defends the great books in this series of tender and candid letters, rich in personal experience and full of humor. Matt Burriesci is a national literary leader, serving as Executive Director of both PEN/Faulkner, which bestows the largest peer-juried prize for fiction

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dead White Guys by Matt Burriesci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

WHAT DO I KNOW?

PLATO

Apology

Your mom thought something was wrong. She said she couldn’t “feel” you.

I could feel you just fine. I put my hand on your mom’s stomach and you kicked. Three days ago we saw you on the ultrasound sucking your thumb. We listened to your heartbeat. The doctor told us you had the hiccups.

Your mom always thought something was wrong. We’d been to the doctor a dozen times now, and every time they said you were fine. Here we go, I thought, rolling my eyes. Another false alarm.

I told her to lie down and wait 15 minutes. You’re paranoid, I said. I joked with the guys at work about my “crazy pregnant wife.” You weren’t due for another two months. It said so right on my calendar: MAY 19th, 9:00 AM VIOLET, right next to my accounting meeting.

But your mom insisted.

Didn’t she know how busy I was? I didn’t have time for pregnancy scares every week. I had important work to do! I was a CEO. The head honcho. I had the corner office and the private bathroom. In just three days, I was leaving for the most important meeting of my life. My assistant reserved me a fancy hotel suite in Denver. When I arrived in Denver, a limousine driver would meet me at baggage claim, holding a sign with my name on it. When I checked into the hotel, the general manager of the hotel would greet me at the door. “Welcome to Denver, Mr. Burriesci,” he’d say, extending his hand. He’d even pronounce my name correctly. I imagine that someone took great care to spell my name phonetically for him. Then he’d hand me a special pin to wear on my lapel. The pin would be shaped like a pineapple. The pineapple pin conveyed a message to the rest of the hotel staff for the duration of my stay: do whatever this man asks you to do. A chilled six-pack of my favorite beer would await me in the Presidential Suite, along with a handwritten note from the national sales manager.

“I’m serious,” she said. “I really think something’s wrong.”

So I sighed, I left an important meeting about my important meeting, and we drove to the doctor for more tests. The doctor assured us, again, that there was no cause for concern.

“Don’t be such a demanding, overachieving mom,” the doctor said, playfully swatting your mom’s arm with the clipboard.

“See?” I told your mom, patting her hand. “Everything’s fine.”

Six days later, your mom almost bled to death while I delivered my important speech on the other side of the country. The doctors cut your mom open and pulled you out. She was in labor for only 20 minutes before you were born, all three pounds, 13 ounces of you.

“It’s possible we might’ve missed something,” the doctor conceded.

The first time I saw you, the flight attendant was telling me to turn off my phone. Your grandpa emailed me a picture. There you were, on your back, unconscious, with your little hands outstretched, and semiclenched. You were in pain, lying in a clear plastic box. A giant tube covered your entire face, and there were wires everywhere. A feeding tube in your belly button. Some kind of glowing monitor snapped onto your foot. It looked like evil scientists were trying to give you superpowers, except your lungs weren’t working and you might die. We could not hold you. We could not feed you. Upstairs from the NICU, your mom was recovering from major surgery.

“You have to think of it like a car crash,” the doctors told me while you both slept. “It’s like they’ve both been in car crashes.”

Your digestive system wasn’t up to speed, so they gave you an IV. You were jaundiced, so they put you under the heat lamp. Your lungs hadn’t fully developed, so they inserted a breathing tube. It was possible your brain had been starved of oxygen, a condition called hypoxia. They’d know better tomorrow. When tomorrow came, they’d know better tomorrow. I needed to sign more forms.

There were other infants in the ward with you, other parents sitting by their sides. We would nod at each other, but we never spoke. We didn’t talk to the other parents in the NICU, and they did not talk to us. Some babies left that ward. Others did not.

You spent the first month of your life in an incubator. Within a few days you were lying in that thing with your arms outstretched as though you were sunbathing. This, to me, has always summed up your natural spirit, Violet. You always bore adversity well. You were cheerful and tough from the start.

I do not handle adversity well. I sure wasn’t cheerful. I’d stopped sleeping normally months ago. I usually slept less than four hours a night. The night before you were born, I didn’t sleep at all, even in my fancy suite in Denver. It had nothing to do with you. I couldn’t sleep because I was filled with anxiety and dread about my “important” job.

I was about to lose that job, and I knew it.

I didn’t know what I would do if I lost my job. 2010 was the height of the Great Recession, and jobs were scarce. I also had a geography problem. I received offers, but all of them were in Washington, DC, a 90-minute commute each way. But we couldn’t move, because we couldn’t sell our house. At the peak of the housing crash, our home lost half its value. We owed the bank more than the house was worth. Even if we could find a buyer, we couldn’t afford to sell, and we couldn’t even rent it out for the cost of the mortgage payment. Like many people at that time, we were stuck.

It would be months before your mom recovered, and you weighed less than four pounds. We needed to feed you every hour. Your mom couldn’t possibly go back to teaching, at least not for another year. She couldn’t even walk upstairs. We had some savings, but only enough to last us a few months. How would I provide for us? What would we do?

I fixated on the worst-case scenario. I was certain I would remain unemployed, burn through our savings, and lose the house. Even before you were born, I was unhinged from lack of sleep and anxiety, and the stress manifested physically. I lost 20 pounds in three months. The skin on my hands and feet broke out in deep and painful sores. I had to cover them with huge gauze bandages and medical tape. I looked like the invisible man.

As you and your mom recovered in the hospital, and all this fear churned in my gut, I went home at nights to prepare the nursery. One night, I removed several tall bookshelves from the room. I started packing up a 54-volume set of The Great Books of the Western World. They’d served as décor in my various abodes since I purchased them at a flea market for $50. I liked having those books around. I even read some of them in college. But mostly I kept them around to make myself feel smart.

I took a break from cleaning, and I opened the first book, which I believed to be a glorified table of contents. The editors had assembled a reading list, 10 Years of Reading. The first book on the list was Plato’s Apology.

In Greek, apologia doesn’t mean “apology” like we understand it. It means “defense speech.” In the context of ancient Athenian trials, the accused would make an apologia, the way a defendant might speak in his own defense today.

Plato’s Apology is the defense speech of the philosopher Socrates, who was put on trial in Athens in 399 BCE, on charges that he was an atheist, and that he’d corrupted the youth of Athens. Socrates was convicted of these charges and sentenced to death. He accepted his sentence and drank poison. Cheerfully.

Socrates was an actual historical figure, but he himself never wrote anything down (or if he did, it’s lost to us). After he was executed, his student Plato used Socrates as a kind of lead character. Our historical notion of Socrates—as the doomed yet noble philosopher who annoys everyone—comes to us almost entirely from Plato’s version of him. It may be that Plato was trying to honor Socrates, and record his teachings faithfully and to the best of his ability. It may be that Plato simply used Socrates as a character, to advance Plato’s own ideas. It could be a bit of both. It doesn’t really matter. The Socratic Dialogues are so engrained in our Western way of thinking that it’s difficult to imagine the world that preceded them.

As original a creature as you may be, Violet, what you think, and the way you think about it, was shaped by Plato. In some sense, we are all Platonists. The same is true of all the authors in this book. Many respond to Plato directly, even thousands of years after his death. As Macedonia is rising, Aristotle responds first, and in quite a contrary manner, disagreeing with Plato almost comprehensively. Centuries later, under the Roman Empire, Augustine will embrace Christianity with help from Plato. In the renaissance, Machiavelli will argue that Plato’s ideas don’t stand up to real-world scrutiny. After the industrial revolution, Karl Marx will claim that Plato’s notions have simply been used as a tool of oppression.

So Plato isn’t just another dude on a list, Violet. The list exists because of Plato. And the hero of Plato’s dialogues is Socrates. Socrates loved wisdom. He did not seek riches, power, glory, or honor, though he seemed to acquire enough of those things to get by. He spent his entire life pursuing wisdom, and at the end of that life, he freely admitted that he possessed no wisdom whatsoever.

In response to the charges leveled against him, Socrates explains that he is not an atheist, and he has not corrupted the youth. These are trumped-up charges. He claims that the most pernicious charge leveled against him is unspoken: that certain Athenians want to punish him, because they claim that Socrates believes himself to be a wise man.

Socrates explains to the court how he obtained this reputation as a wise man. A long time ago, he and a friend visited the Oracle at Delphi. The friend decided to ask the Oracle if anyone in the world was wiser than Socrates.

My friend asked the oracle to tell him whether anyone was wiser than I was, and the Pythian prophetess answered, that there was no man wiser.

Socrates didn’t know what the Oracle could possibly mean by this.

I said to myself, what can the god mean? And what is the interpretation of this riddle? For I know that I have no wisdom, small or great. What then can he mean when he says that I am the wisest of men? And yet he is a god, and cannot lie; that would be against his nature.

Socrates decides to test the Oracle. He visits all the people that he believes must be wiser: the politicians, the poets, and the craftsmen.

First Socrates visits a politician renowned for his wisdom. This particular politician had great power and responsibility. Surely, Socrates could quickly dispatch the Oracle by proving that this ruler was wiser. But Socrates is surprised after speaking with the ruler.

When I began to talk with him, I could not help thinking that he was not really wise, although he was thought wise by many, and still wiser by himself.

Even though the politician knows how to pass legislation, wage war, and navigate various factions, he doesn’t possess any actual wisdom. He just knows how to do some stuff. But he thinks that this knowledge makes him wise. Socrates must admit that, though he himself is not wiser than the politician, at least he knows that he doesn’t know.

I suppose I am better off than he is, for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think I know. In this latter particular, then, I seem to have slightly the advantage on him.

Then Socrates decides to visit the great poets. Surely they have to be wise! They produce beautiful art that inspires people. They can recite the great poems of antiquity. But again, Socrates is disappointed.

There is hardly a man here who would not have talked better about their poetry than the poets did themselves.

Socrates concludes that the poets act from divine inspiration. Just because they possess talent doesn’t mean they possess any wisdom. But like the politician, they, too, thought that they were wise.

All right, Socrates said: I’ll go talk to the craftsmen. They have to be wiser than I am. They produce useful and necessary things for society. But again, he finds that all the tradesmen think that they’re wise because they can manage money, build a boat, or make a horseshoe. Socrates leaves them the same way he left the others, thinking, Well, they aren’t wise, either, but they still think that they are.

So now Socrates has pissed off everyone: the politicians, the poets, and the tradesmen, because he’s told them all that their knowledge amounts to doodley squat. This, says Socrates, is why he’s really on trial, and not this business about atheism or corrupting the youth, which is nonsense. And then he explains what the Oracle actually meant.

But the truth is, O men of Athens, that God only is wise; and by his answer he intends to show that the wisdom of men is worth little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name by way of illustration, as if he said, “He, O Men, is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing.”

I thought my job was so important. I thought I was so important. Suddenly you were here, and I didn’t know if you would ever leave the hospital. I didn’t know how to take care of you, or even if I could take care of you. I didn’t even know who I was, or what I wanted, or what was important in life. But it certainly wasn’t my job, my ambition, or the value of my home. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: Dear Violet

- 1. What Do I Know?—Plato, Apology

- 2. When Is It Right to Do the Wrong Thing?—Plato, Crito

- 3. Have We Become Gods?—Aristophanes, The Clouds

- 4. Is There Any Justice in the World?—Plato, Republic

- 5. What Is Happiness?—Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book I

- 6. Is the Customer King?—Aristotle, Politics, Book I

- 7. Who Should Be in Charge?—Plutarch, The Life of Lycurgus

- 8. The State as Church—Plutarch, The Life of Numa Pompilius

- 9. Punch the Bully in the Face—Plutarch, The Life of Alexander

- 10. Hubris—Plutarch, The Life of Julius Caesar

- 11. What Would Jesus Do?—St. Matthew, The Gospel of Jesus Christ

- 12. Can People Change?—St. Luke, The Acts of the Apostles

- 13. How Can God Let Bad Things Happen?—St. Augustine, The Confessions

- 14. Do the Ends Justify the Means?—Machiavelli, The Prince

- 15. What’s Your Major?—Montaigne, Of the Education of Children

- 16. Is America Exceptional?—Montaigne, Of Cannibals

- 17. Why Am I Afraid?—Montaigne, That the Relish of Good and Evil Depends in Great Measure Upon the Opinion We Have of Them

- 18. What Don’t I Know?—Montaigne, That It Is Folly to Measure Truth and Error by Our Own Capacity

- 19. What If Life Is Meaningless?—William Shakespeare, Hamlet

- 20. What Is Government For?—John Locke, Concerning the True Original Extent and End of Civil Government

- 21. What’s Best for Everyone?—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

- 22. Are Gods Immortal?—Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapters 15-16

- 23. What Are “American Values”?—Various, including Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, The Declaration of Independence

- 24. Your Rights* *Subject to Change at Any Time.—Various, The Constitution of the United States

- 25. Is Greed Good?—Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

- 26. Does Capitalism Work?—Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party

- Bibliography

- About the Author