![]()

I have power, because I am a Chair, in the sense that I am a university professor. This relationship between the chair and authority dates back to the fifteenth century, when meetings were first chaired, and it continues today.1 This humble object can also mark out space and define territory, excluding the rest of the world and creating a powerful presence at the same time:

Desperate for the waiters to leave, he [Edward] and Florence turned in their chairs to consider the view of a broad mossy lawn, and beyond, a tangle of flowering shrubs and trees clinging to a steep bank that descended to a lane that led to the beach.2

When did the power of the chair to include and exclude, to display power, to signal intimacy – as in this case – begin? It dates back some 4,000 years to the time of the ancient Egyptians, when the chair first became a vital signifier of power relations and social mores. At that time the chair reflected the status of the individual who commissioned and used it. And up until the nineteenth century the vast majority of the world’s population had experience only of looking at a dignitary sitting in a chair, as opposed to sitting on one themselves. Whether pharaoh, maharaja, pope or emperor, the chair was reserved largely for the elite. With the impact of modernity, new economic, political and social forces meant that the chair became more common in everyday life, and was used to display hierarchies of power; different chairs were used by different sections of society, within both the Victorian domestic and public spheres in the West. Forms of Western etiquette and culture have been gradually assimilated globally, with the infiltration of modernity. The relationship between socio-political power and the chair changed dramatically, from being a signifier of the elite during the time that they were scarce, to a tool for suppression as they became ubiquitous in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This chapter charts the process.

The origin of the word chair itself lies in representations of power. Originating from the Greek noun kathedra, deriving from kata ‘down’ and hedra ‘seat’, kathedra meant an important chair, one used by a teacher or professor. This was adopted into Latin as cathedra. In late Latin this transformed into cathedralis, to mean ‘belonging to the bishop’s seat’. The word cathedral was then used in English from the thirteenth century as an adjective to denote a bishop’s church in the sense of a cathedral church, the place where the bishop’s seat could be found. This was shortened simply to cathedral by the sixteenth century. The word chair derives from this Greek origin. Whilst the bishop sat in a ceremonial chair, and the priests in stalls on either side, the congregation knelt on stone floors, reinforcing power relations. The use of the term Chair to denote a professor also stems from this etymology.

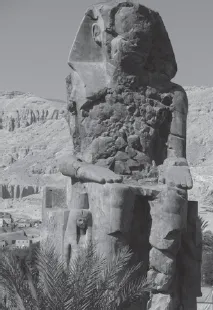

The earliest examples of chairs date back to ancient Egypt and the time of the Old Kingdom and the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2498 BC), when the vast majority did not experience the status of owning or even sitting on a chair. This was reserved for the upper echelons of society. The chair in ancient Egypt was a device to distinguish the elite by raising them physically to a higher level than that of the peasants and slaves, who squatted on the ground – the hierarchy of society was set out by means of the chair. This is particularly visible in Egyptian statues, which reinforced the status of the sitters by means of chairs or thrones. The high point of ancient Egyptian culture was the New Kingdom, where the location of central power was Thebes (today’s Luxor) from 1550 to 1069 BC. The monumental temples there and at Karnak were built and expanded by a succession of powerful pharaohs, supported by a vast army of priests, administrators and craftworkers. The pair of immense Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1550–1295 BC) limestone statues represents the power of Amenhotep III. Reaching an impressive 18m (59ft) into the sky, the enthroned figures were erected to protect his mortuary temple on the west bank of the Nile. The culture of building pyramids had been superseded by underground tombs, carved into the limestone of the arid Valley of the Kings. This was to evade the thieves who regularly raided the tombs, since they were filled with treasures and rare objects, placed in the tombs with the mummified body of the pharaoh for the afterlife.

Egyptian limestone statue of Amenhotep III, 18th Dynasty. Luxor, Egypt.

Since the tombs were deliberately secreted in the hillside, there is a constant process of discovery and 62 have been located to date. Because of the culture of packing the tombs with objects for the afterlife and the dry and hot weather conditions of Egypt, many chairs have survived the 3,000 years since their original incarceration. The most famous tomb is that of Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC). Discovered by Howard Carter in 1922, the tomb contained a vast array of treasures, including ritual objects, weaponry, games, jewellery and furniture. The antechamber and annexe of the tomb were packed with a selection of stools and chairs, stacked haphazardly. Six chairs were found in the tomb in total, the most famous one being the Golden Throne. Now on display in the Cairo Museum, the regal chair was originally wrapped in black linen and was found in the antechamber, wedged beneath the Ammut couch.

Tutankhamun’s Throne, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt, 18th Dynasty.

The throne is made of wood and decorated with gold and silver sheets ornamented with semi-precious stones and glass. The sloping back is the main focus of the chair, and it is decorated with an image of the seated Tutankhamun and his queen, Ankhesenamun. The other five chairs discovered in the tomb include a finely carved, African ebony chair with ivory inlay and gold-leaf decoration and an important example of a backed folding stool, known as the Ecclesiastical Throne. The seat is constructed from an X-frame in the fashionable, if surprising, form of ducks’ heads. Constructed from ebony, decorated with gold leaf, glass, faience (a composite material made from ground quartz with alkaline glaze) and coloured glass, these richly decorated chairs affirm the regal status of Tutankhamun. Objects like these are rare and precious, museum pieces that attest to the powerful mythologies of ancient Egyptian culture.

From Egyptian times onwards, thrones have been used to single out the most prestigious members of society. During the Tang Dynasty in China (AD 618–906), chairs were adopted by the elite to mark out prestigious roles. By the time of the late Ming Dynasty (AD 1368–1644), the chair remained as a status symbol, with most of the population using stools. Whether for monarch, pope or bishop, the throne denoted authority, most notably since early examples could be lifted up and carried, or even secured on the back of an elephant, to display the powerful individual to the assembled throngs, as a fantastic spectacle. For example, in India:

Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s throne, early 19th century.

Since their earliest contact with Europeans, Indian rulers demonstrated an interest in rare and exotic goods from the West, which were rapidly assimilated into the decoration of Indian palace interiors. Those rulers who interacted with Europeans also began to adopt aspects of Western lifestyle and behaviour, such as sitting on a chair instead of on textiles on the ground, or using a carriage instead of a palanquin.3

The throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, which dates from the early nineteenth century, represents a significant blend of Asia and Europe, the traditions of East and West. The chair is octagonal in shape, based on the courtly furniture of the north Indian Mughals. The throne was created by Hafiz Muhammad Multani, a goldsmith, which is fitting since the wood and resin core is completely covered with sheets of repoussé, chased and engraved gold. Every inch of the surface is covered in delicate patterns, including subtle lotus flowers, symbols of purity and creation, and associated with thrones for the Hindu gods. The throne was designed to be carried in processions, and has handles on its sides for this purpose. The chair is squatter than Western examples of the time, because the maharaja would sit cross-legged on the cushion, as was the Indian custom. But the chair carried at a height in processions ensured that his royal status was confirmed.

Chair of State and Footstool for the coronation of Charles II, 1661.

Chairs also played a crucial role in royal events in Britain, to delineate particular roles in the ceremony of crowning the monarch, for example. The Gothic Coronation chair in Westminster Abbey is the oldest chair in England to be still used for the purpose for which it was created. Made in 1300–01 for Edward I, it has been used for the coronation of British monarchs ever since. It was decorated with plants, birds and animals by the court painter, Master Walter. A later example of a ceremonial chair is the Chair of State and Footstool used for the coronation of Charles II, created in 1661 by the royal upholsterer John Casbert for the Archbishop of Canterbury. Richly upholstered and decorated for that occasion, the chair has a beech frame and upholstered in purple velvet and a fringe of gold wire. The base is in the X-frame form, first seen in ancient Egypt and created for folding chairs. At this time, social interaction would take place in the bedchamber around the bed. Guests were received into the royal chamber and sat wherever they could, including on the floor.

The folding form of chair was used by emperors of the Ming Dynasty for the purposes of travel, either to military campaigns or to the tombs of ancestors to make sacrifices. One example, now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, was made from intricately carved lacquer on wood at the Orchard Factory in Beijing. The Chinese normally knelt on mats on the floor, and a platform arrangement was used up until the nineteenth century, to raise high-ranking officials and religious leaders above the masses during important ceremonies.

At the same time in Britain, only the most prominent figures in a domestic or royal interior would sit on a chair. As Sigfried Giedion, the modernist design theorist claimed in 1948:

But as late as the first half of the sixteenth century, chairs are not the rule, even in the highest places. When Hans Holbein the Younger portrays Henry VIII and his privy council in 1530, his woodcut shows the members of this exalted body as tightly packed on low-back benches as were the members of the Lit de Justice in 1458. The unpainted, primitively joined benches, tables, and chairs found in the Alps today, or among the American colonists well into the nineteenth century, represent the domestic tradition of the late Gothic carried through the ages. Such furniture was everywhere to be found at the turn of the fifteenth century in the North as in the South. Its tradition took shape in the towns, and at the behest of burghers and patricians. It bears still the imprint of medieval austerity.4

For example, the Bromley-by-Bow room, which dates from 1606, and which has been preserved at the Victoria & Albert Museum, contains one carved wooden chair with a cushion on the seat, which would have been very prestigious for its occupant. The rest of the household would have sat on stools or benches against the wood-panelled wall, the lower-status seating having no backs.

It was the French court, which moved to the showplace of Versailles in 1682, that established the most intricate hierarchy expressed by means of chairs. The absolute monarch Louis XIV established the accepted practice for behaviour at court throughout Europe in the seventeenth century. The court grew in size from 600 in 1664 to 10,000 in the late eighteenth century, after the court had moved to Versailles, and the sovereign kept order partly through the use of the chair. Only a tiny elite – including his brother, his children and grandchildren – was allowed to sit while the king was sitting, and this was only on stools. For example, in the Hall of Mirrors the ‘Sun King’ sat on his grand, Baroque silver throne; a canopy towered above his bewigged head, surmounted with a huge crown. The throne was placed at the top of a stepped platform to give extra height and prominence whilst the gathered assembly stood. Louis XIV also had a special wheeled chair, or roulette, to transport him around the huge gardens of Versailles; so again, his entourage gathered around him on...