- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

DNA-targeting Molecules as Therapeutic Agents

About this book

There have been remarkable advances towards discovering agents that exhibit selectivity and sequence-specificity for DNA, as well as understanding the interactions that underlie its propensity to bind molecules. This progress has important applications in many areas of biotechnology and medicine, notably in cancer treatment as well as in future gene targeting therapies.

The editor and contributing authors are leaders in their fields and provide useful perspectives from diverse and interdisciplinary backgrounds on the current status of this broad area. The role played by chemistry is a unifying theme. Early chapters cover methodologies to evaluate DNA-interactive agents and then the book provides examples of DNA-interactive molecules and technologies in development as therapeutic agents. DNA-binding metal complexes, peptide and polyamide–DNA interactions, and gene targeting tools are some of the most compelling topics treated in depth.

This book will be a valuable resource for postgraduate students and researchers in chemical biology, biochemistry, structural biology and medicinal fields. It will also be of interest to supramolecular chemists and biophysicists.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

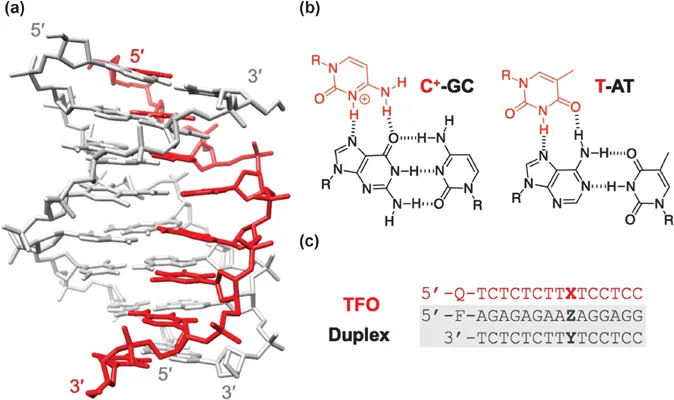

1.1 Why Triplexes?

1.1.1 Triplets and Triplex Motifs

1.1.2 Base, Sugar and/or Phosphate Modifications

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1 DNA Recognition by Parallel Triplex Formation

- Chapter 2 Interfacial Inhibitors

- Chapter 3 Slow DNA Binding

- Chapter 4 Thermal Denaturation of Drug–DNA Complexes1

- Chapter 5 Computer Simulations of Drug–DNA Interactions: A Personal Journey

- Chapter 6 Binding of Small Molecules to Trinucleotide DNA Repeats Associated with Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Chapter 7 Parsing the Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation Phenomenon of General DNA–Ligand Interactions by a ‘Gradient Determinant’ Approach

- Chapter 8 Structural Studies of DNA-binding Metal Complexes of Therapeutic Importance

- Chapter 9 Therapeutic Potential of DNA Gene Targeting using Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA)

- Chapter 10 Sequence-selective Interactions of Actinomycin D with DNA: Discovery of a Thermodynamic Switch

- Chapter 11 Molecular Modelling Approaches for Assessing Quadruplex–Small Molecule Interactions

- Chapter 12 Molecular Recognition of DNA by Py–Im Polyamides: From Discovery to Oncology

- Chapter 13 Synthetic Peptides for DNA Recognition Inspired by Transcription Factors

- Chapter 14 Targeting DNA Mismatches with Coordination Complexes

- Chapter 15 CRISPR Highlights and Transition of Cas9 into a Genome Editing Tool

- Subject Index