![]()

CHAPTER 1

Conducting Polymer-based Carbon Nanotube Composites: Preparation and Applications

SANG-HA HWANGa, JEONG-MIN SEOb, IN-YUP JEONb, YOUNG-BIN PARK*a AND JONG-BEOM BAEK*b

aUlsan National Institute of Science and Technology, School of Mechanical and Advanced Materials Engineering/Low Dimensional Carbon Materials Center, 100, Banyeon, Ulsan 689-798, South Korea;

b Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Interdisciplinary School of Green Energy/Low Dimensional Carbon Materials Center, 100, Banyeon, Ulsan 689-798, South Korea

*E-mail:

[email protected] or

[email protected] 1.1 Discovery of Conducting Polymers

Polymers have traditionally been considered to be good electrical insulators, and a variety of applications have relied on this insulating property. However, in 1958, Natta et al.1 succeeded in synthesizing polyacetylene (PA), a semiconducting conjugated polymer, which paved the way for the upsurge in conjugate polymer research that followed in the decades to come. Alan Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa made the revolutionary discovery that plastic can be electrically conducting in the 1970s.2 As a result, they were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000. For a polymer to be electrically conducting, it must “imitate” a metal—that is, the electrons must be freely mobile and not bound to the atoms. One way to achieve this, is to have the polymer backbone consisting of alternating single and double bonds, called “conjugated double bonds”, between carbon atoms. It must also be “doped”, which means that electrons are removed (through oxidation) or introduced (through reduction). The resulting holes or extra electrons can move along the macromolecule, which would, in turn, make the polymer electrically conducting.3,4

The chemical origins of such a remarkable difference in the material properties between various types of polymers can be readily rationalized. Traditional polymers, such as polyethylene or polypropylene, are made up of essentially σ-bonds; hence, a charge once created on any given atom on the polymer chain is not mobile (static charge). The presence of an extended π-conjugation in polymers, however, confers the required mobility to charges that are created on the polymer backbone (by the process of doping) and makes them electrically conducting. One problem is that, due to the presence of this extended conjugation along the polymer backbone, the chains are rigid and possess strong inter-chain interactions, resulting in insoluble and infusible materials.5,6 These conjugated polymers, hence, lack one of the most important and useful properties of polymers, namely the ease of processability. More recently, however, it was demonstrated that when lateral substituents were introduced even conjugated polymers can be made soluble (hence, processable) without significant decrease in their electrical conductivity.7,8 Another problem in technological application is the inherent chemical instability, especially, in the doped form, to ambient conditions.9 Today, conducting polymers that are stable even in the doped form have been developed. We shall highlight some specific examples of such systems and discuss some of their research progress and potential applications.10–12

PA, in view of possessing the simplest molecular framework, has attracted the most attention, especially of physicists, with an emphasis on understanding the mechanism of conduction. However, its insolubility, infusibility and poor environmental stability had rendered it rather unattractive for technological applications.13 The technologically relevant front runners belong to essentially four families: polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), polythiophene (PT) and poly(phenylene vinylene) (PPV). PANI is rather unique as it is the only polymer that can be doped by a protonic acid and can exist in different forms depending upon the pH of the medium.14 A few of the more important conducting polymers and their molecular structures are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Chemical structures of some undoped conducting polymers.

1.2 Synthesis of Conducting Polymers

Conducting polymers can be synthesized either chemically or electrochemically, and each of their advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 1.1.15 Through the chemical polymerization approach, the conjugated monomers react with an excess amount of an oxidant in a suitable solvent, such as acid. The polymerization takes place spontaneously and requires constant stirring as the reaction progresses.16 The second method is via electrochemical polymerization, which involves placing both the counter and reference electrodes (such as platinum) into the solution containing the diluted monomer and electrolyte (the dopant) in a solvent. After applying a proper voltage, the polymer film immediately begins to form on the working electrode. A major advantage of chemical polymerization is associated with the mass reproducibility or scalability at a reasonable cost, which is a problem associated with electrochemical methods. On the other hand, an important feature of the electropolymerization technique is the direct formation of conducting polymer films that are highly conductive for use especially in electronic devices.17

Table 1.1 Comparison of conducting polymer polymerization methods.15

| Polymerization method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Chemical polymerization | Possibility of large scale production | Cannot make thin filmRelatively complicated |

| Post-covalent modification of bulk polymer is possible | |

| More options to modify polymer backbone covalently | |

| Electrochemical polymerization | Easy to synthesizeDirectly applicable to thin film synthesisSimultaneous doping | Detachment from electrode surface is difficult |

| | Post-covalent modification of bulk polymer is difficult |

1.3 Conductivity and Doping of Conducting Polymers

In general, materials with conductivities less than 10−8 S cm−1 are considered as insulators, materials with conductivities between 10−8 and 103 S cm−1 are considered as semiconductors, and materials with conductivities greater than 103 S cm−1 are considered as conductors. Conducting polymers in their pristine (undoped) states are usually considered as semiconductors or insulators, having a band gap energy excessively high for the thermal excitation of a significant number of charge carriers. Therefore, undoped conducting polymers, such as PA and PT, show electrical conductivities of only 10−10–10−8 S cm−1 (Figure 1.2).18 Upon the doping of conducting polymers, there is a dramatic increase in the electrical conductivity by several orders of magnitude up to values of approximately 10−1 S cm−1, even at very low level of doping, for example, less than 1%. Subsequent doping to higher levels results in the saturation of the conductivity at values in the range 102–105 S cm−1, as shown in Figure 1.3.1 Heavily doped, stretch-oriented PA has the highest reported electrical conductivity among the conducting polymers, with the confirmed value of 80 000 S cm−1.19

Figure 1.2 Full range of conductivity from insulators to metals.18

Figure 1.3 Electrical conductivity (room temperature) of PA as a function of the dopant concentration. Stretch-oriented samples exhibit much higher conductivity values.2

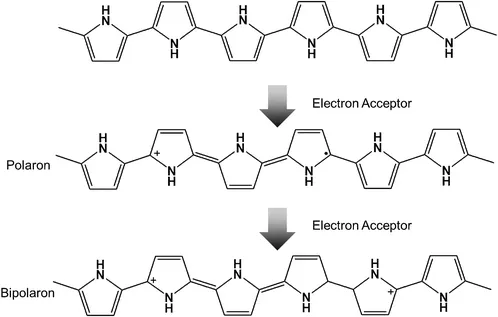

In the case of conventional inorganic crystalline semiconductors, such as silicon and germanium, doping occurs through the substitutional insertion of atoms (dopant) with a higher or lower valence band than the host semiconductor for n-type or p-type doping, respectively. For example, phosphorous (5 valence electrons) providing an extra electron to the silicon (4 valence electrons) lattice semiconductor band structure leads to n-type doping. However, doping in a conducting polymer is the process of oxidizing (p-doping) or reducing (n-doping) a neutral polymer and providing a counter anion or cation (i.e., dopant), respectively. Upon doping, a conducting polymer with a net charge of zero is produced due to the close association of the counter ions with the charged polymer backbone. This process introduces charge carriers, in the form of charged polarons (i.e., radical ions) or bipolarons (i.e., dications or dianions), into the polymer (Figure 1.4).20

Figure 1.4 Polaron and bipolaron formation on the conjugated backbone of PPy.20

As summarized in Figure 1.5, charge injection by doping can be achieved in several ways.21 Each of the methods of doping illustrated in Figure 1.5 leads to unique and important phenomena. For chemical and electrochemical doping, the induced electrical conductivity is permanent until the carriers are either chemically compensated or until the carriers are purposely removed by “dedoping”. In the case of photoexcitation, the photoconductivity is transient and lasts only until the excitations are either trapped or decay back to ground state. For charge injection at an interface, electrons reside in the π*-band, and holes reside in the π-band only as long as the bias voltage is ...