![]()

Part 1: The Plant Perspective

2 Plants Attracting Insects

2.1 Introduction

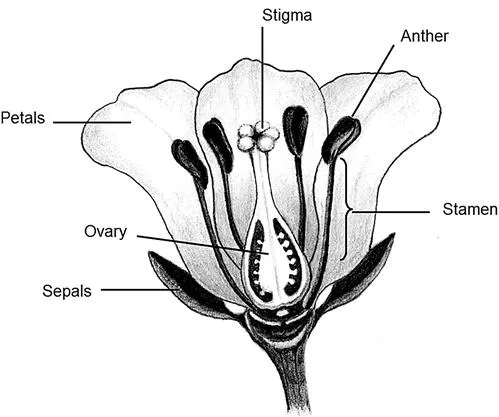

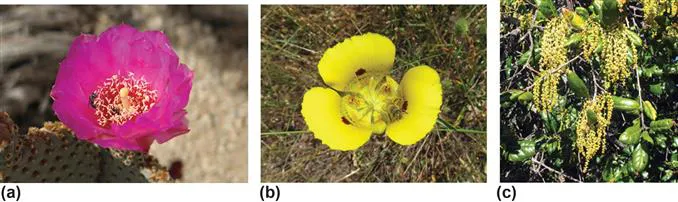

Survival and successful reproduction are essential for the continuation of life for all living things. As for plants, reproduction greatly depends on insect pollination. In about two thirds of all the species of flowering plants, known as the angiosperms, insects pollinate the flowers by moving pollen from the male anthers of one flower to the female stigma of another flower of the same species. (Figure 2.1 shows a schematic drawing of the basic parts of a flower.) Pollination induces fertilization of the plant, followed by seed production, and thus promotes reproduction of the species. Organic compounds produced by the plants have major roles in advertising to potential pollinators and attracting them. Many plants feature colors in their flowers that are visible and appealing to insect pollinators (Figure 2.2(a) and (b)). In addition, flowers emit attractive scents when ready for pollination. Many flowers also offer sweet nectars and ample pollen as food, to further entice insects to visit.

Figure 2.1 Schematic drawing of the flower parts of a flowering plant. (Drawing by Eveline Larrucea.)

Figure 2.2 Insect-pollination versus wind-pollination. (a) Colorful flowers with plenty of pollen, like the blossoms of a beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris), attract pollinating insects. (b) Brightly-colored flower petals, with nectar guides and floral nectar, attract beetle pollinators in a yellow mariposa tulip (Calochortus luteus). (c) Wind-pollinated plants, like live oaks (Quercus sp.), have inflorescences with inconspicuous colors and produce large amounts of pollen.

Fossil finds of plants and insects have shown that towards the end of the early Cretaceous era, between 130 and 90 million years ago, a rapid evolution of plants and insects occurred. Diversification of plants, with fast-increasing numbers of plant species, took off when insects started to evolve during that time period. It is generally assumed that it was the diversification of nectar- and pollen-collecting insects that greatly drove the evolution of plants.1

Compared to pollination by insects, pollination by wind is the more ancient form in evolutionary terms. Examples of wind-pollinated plants are pines (Pinus spp.), oaks (Quercus spp., Figure 2.2(c)), and all the grasses (Poaceae). Wind-pollinated plants tend to have drab floral parts and no nectar. This type of pollination obviously requires wind and also masses of pollen which is randomly dispersed into the surrounding space. Insect pollination, on the other hand, requires smaller quantities of pollen for successful fertilization. Insects seek out plants that have the proper attractive features in the form of enticing colors and smells, aside from inviting floral shapes, and tend to be quite faithful to the particular plant species they visit. Efficient mixing of plant genes takes place as insects transport male genetic information contained in pollen to the female floral parts of another flower of the same species. Self-pollination in insect-pollinated flowers is uncommon. In contrast to dispersal of pollen by wind, pollination by insects can successfully occur in scattered and isolated plant populations, as can be found in tropical forests. Specific floral scents and attractive pigments direct insects to isolated plants of the same species at considerable distances, and pollinating insects can detect and visit the matching plants.

2.2 Plant Volatiles That Attract Pollinating Insects

Plants produce large numbers of volatile compounds, i.e. compounds that easily evaporate into the air. More than 1700 different volatile organic compounds, sometimes abbreviated as VOCs, have been identified in flowers alone.2 We notice these volatiles if they have distinct odors to us, pleasant or unpleasant, especially on a warm day. (Note that the characterizations of the nature of the smells are necessarily from a human point-of-view.) Scents emitted by flowers alert potential pollinators. Because plants are mostly rooted in one place, the volatiles are a means of long-distance communication with other organisms, like insects. Compared to visual cues from flowers such as colors, odorous volatiles are randomly sent into the surrounding space and thus have low directionality. Concentrations of the scents emitted by flowers are affected by wind conditions and can be disturbed by smoke, as from forest fires, and other pollutants.3 The scents, together with appropriate floral colors and shapes of the flowers, are inviting to select pollinators.

Some flowers attract a broad range of pollinators, whereas others only appeal to a few types of insects. Sweet scents, like the strong fragrance of the damask rose (Rosa damascena) (Figure 2.3(a)), are generally attractive to butterflies, bees, and bumble bees. Moths are lured by heavy, aromatic smells of flowers that tend to open later in the day, like the blossoms of white jasmine (Jasminum sp.) (Figure 2.3(b)). Maroon-colored or brown inflorescences often produce smells of decaying fish or of carrion, and are attractive to flies or small gnats. Floral smells are emitted during specific times of a plant’s growth phase, such as during the opening of flowers. Some plants even enhance the evaporation of attractive compounds, heating up during the flowering phase by increasing metabolic rates. This phenomenon is especially common in plants of the Arum family. A famous example is the Sumatran corpse plant (Amorphophallus titanum, Figure 2.3(c)) whose giant inflorescence can heat up by more than 10 °C, sending out volatiles with a rotten-meat smell that attracts fly pollinators.4

Figure 2.3 Fragrant and foul-smelling flowers. (a) Damask rose (Rosa damascena) is a highly fragrant, sweet-smelling rose. (b) Heavy-scented jasmine flowers (Jasminum sp.) release their fragrance late in the day, attracting moths. (c) A large inflorescence of the corpse plant (Amorphophallus titanum), about two meters tall, is ready to open and to release foul-smelling volatiles that attract flies.

We shall encounter volatile compounds again in a later chapter, but there the volatiles are emitted not from flowers but from plant parts like leaves and needles. Under these circumstances, the volatiles can act as deterrents towards insects and other animals, keeping the browsers from feeding on the plants and thus supporting the plants’ survival.

2.3 Compositions of Plant Scents

Plant scents are mixtures of sometimes more than a hundred different volatile organic compounds. These compounds are generally oily liquids at ambient temperatures. This property gave them the general name essential oils, ‘essential’ here meaning the characteristic or essence of a scent. The composition of a plant scent is influenced by the type of plant, its age, its growth phase, and the time of day, as well as the local climate and the soil conditions. These factors also determine the concentrations, i.e. the percentages, of compounds found in a particular fragrance.

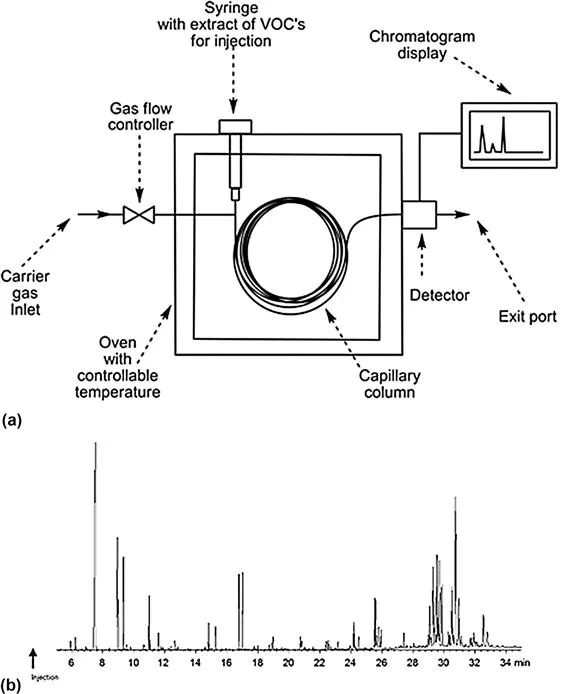

If we want to determine the components of a floral scent, the most commonly used method is gas chromatography (GC) combined with mass spectrometry (MS). Gas chromatography is a highly sensitive analytical method that is used to separate mixtures of volatile compounds, requiring only fractions of a microliter (i.e. 10−6 liters) for analysis. It is therefore a most valuable method to separate and examine mixtures of volatiles for which only very small quantities are available. This certainly applies to essential oils in floral fragrances of which often only trace amounts are present.5

In order to study the components of a fragrance by GC, we first need to collect a sample of the scent mixture. A frequently-used, gentle method is head-space analysis. Figure 2.4 shows a head-space analysis set-up for collecting volatiles emitted by the fragrant flowers of a ylang ylang shrub (Cananga odorata). A glass bell jar is placed over the fragrant flowers and connected with a probe containing a material that can absorb volatile oils. The floral volatiles are pulled with a pump into the probe. This method is non-destructive to the plant parts. The collected oils are eluted, i.e. rinsed, from the probe with appropriate solvents and can then be further separated and analyzed by gas chromatography (Figure 2.5). If combined with mass spectrometry (MS), the identity of the single compounds in a mixture can be determined by GC-MS. Figure 2.5(a) shows a schematic picture of a gas chromatograph. Figure 2.5(b) displays an example of a gas chromatogram of a sample of a mixture of volatile oils, as in a floral scent, with each line in the chromatogram representing a different compound.6

Figure 2.4 Head space analysis set-up to collect volatiles emitted by the fragrant flowers of an ylang shrub (Cananga odorata), Longwood Gardens, Pennsylvania. (Photo Courtesy Longwood Gardens.)

Figure 2.5 Analysis of a mixture of volatile compounds, as in a floral scent, by gas chromatography. (a) Schematic drawing of a gas chromatograph. (b) A sample gas chromatogram of a mixture of volatile oils. (Gas chromatogram by Phenomenex, Inc.)

In a related method, used to evaluate the odor contributions of the compounds in a volatile mixture, a ‘sniffing port’ is attached to the exit port of the gas chromatograph. Each compound can then be smelled as it is being separated and can be further evaluated for its individual odor quality. Humans have no odor perception of some compounds in the volatile mixtures of plant scents, but these may well be recognized by animals like insects. (After all, plants did not evolve floral scents to attract humans.) The sensitivity towards different volatiles can be very different among insects, and a higher percentage of a volatile compound in the mixture does not necessarily mean that it is more easily perceived. On the other hand, volatiles present in trace amounts can be crucial scent comp...