![]()

CHAPTER 1

The History of Wine

1.1 THE PREHISTORY OF WINE

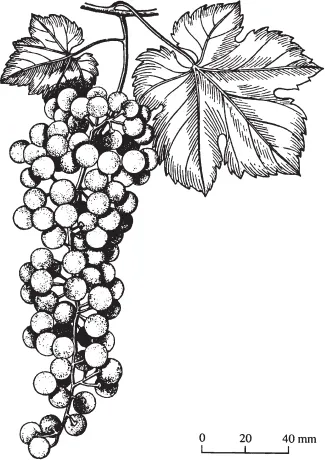

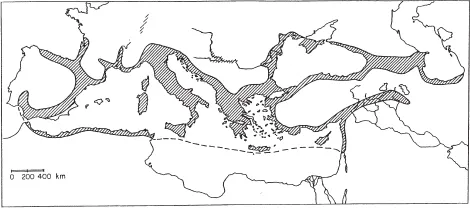

Homo sapiens would have probably encountered Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris (Figure 1) at a very early date, when the first groups of humans migrated from East Africa some 2 million years ago. The most likely venues for making the acquaintance were the upland areas of eastern Turkey, northern Syria or western Iran, or, maybe, the hilly lands of Palestine and Israel, or the Transjordanian highlands. Significantly, most eastern Mediterranean myths pinpoint the origin of viniculture to somewhere in north-eastern Asia Minor. In theory, however, the event could have occurred anywhere within the distribution range of the wild grapevine (Figure 2). As we have already intimated, Palaeolithic man was probably the first to become familiar with wine, purely by the accidental ‘spoilage’ of stored, or over-ripe grapes. Wine may, of course, have been the result of unsuccessful attempts to store grape juice, which is a particularly unstable beverage. Because our Stone Age forebears did not dwell in permanent, year-round settlements, they had no opportunity to investigate what was actually happening when grapes/grape juice spoiled (fermented), and so they were unable to learn about and perfect the process. It was not until man adopted a sedentary way of life, and had developed the need for a continuous supply of wine, that he put his mind to a rudimentary form of viticulture. From what we know at present, the Neolithic period in the Near East, somewhere between 8500 and 4000 BC would seem to provide all prerequisites for the intentional manufacture of wine. Not only was mankind flirting with agriculture and beginning to lead a settled existence, but was starting to manufacture items such as pottery vessels, essential items if liquids were to be stored for any period of time.

Figure 1 Wild grapevine Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris (after Zapriagaeva1)

Figure 2 The distribution range (shaded area) of V. vinifera subsp. sylvestris. Note that towards the east the wild vine extends beyond the boundaries of this map, and reappears at a few places in Turkmenistan and Tadzhikistan (After Zohary & Spiegel-Roy10)

(Reproduced by kind permission of the American Association for the Advancement of Science)

The world’s earliest known pottery, from Japan, dates to the 11th millennium BC, but it seems to have been ‘invented’ independently in many places throughout Anatolia, Mesopotamia and the Levant almost simultaneously around 7000–6000 BC. The earliest pots were simple cups, vases and dishes, probably originally sun-dried. Later, more sophisticated vessels were fired in kilns. Although probably used by nomadic peoples, pottery was a real benefit for those with a sedentary life style. With the domestication of plants and animals, clay pots provided a sound way to store liquids (e.g. milk, fruit juice), and, most importantly, the wherewithal for cooking (heating and boiling) and fermenting. The inventor of the first clay pot is unknown, but its creation was most likely attributable to women who carried most of the burden for domestic chores. The ability to heat food, and to ferment, opened up a whole new world of potential food sources that were safer, tastier and easier on the digestive tract.

If we are looking for a single site for the origin of the domestic grapevine (the Noah ‘hypothesis’), then, according to the archaeological, archaeobotanical and historical information that we have at present, some northern mountainous region of the Near East would appear to be the most likely ones. With the ingenuity of Homo sapiens, and the vast natural range of the wild vine, it is tempting to suggest that there might have been multiple domestications of the plant in different places, and at slightly different times. This is not impossible, but all the available evidence does seem to point to an upland site in the northern part of the Near East.

As we shall see, the earliest confirmed traces of wine have been found in sediments in a pottery jar from the Neolithic village of Hajji Firuz in north-eastern Iran. Relatively little is known about wine making at Neolithic sites further north and at higher altitudes in the Taurus and Caucasus mountains, where the wild subspecies of V. vinifera thrives today. Domesticated grape seeds have been recovered from Chokh in the Dagestan mountains of the eastern Caucasus, dating from the beginning of the 6th millennium BC, and from Shomutepe and Shulaveri along the Kura River in Transcaucasia, dating from the 5th through early 4th millennia BC. Should confirmatory residue analysis from pottery fragments from these areas ever be possible, then we may be able to locate the ultimate origins of viticulture. Unfortunately, few Neolithic sites in this vast region have, so far, been excavated. It has long been thought that the domestication of V. vinifera occurred in Transcaucasia, or in neighbouring Anatolia, around 4000 BC. The region between and below the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, where the grapevine is indigenous, represents the closest the vine comes to the Near Eastern origins of plant and animal agriculture. As Jackson2 says: ‘Therefore it seems reasonable to assume that grape domestication may have first occurred in the Transcaucasian Near East.’ Certainly, as far as Vavilov’s ‘centres of genetic diversity’ are concerned, it is in this Transcaucasian region that wild grapevines are both the most abundant and most variable. Before this, of course, wild vines would have been used as a source of grape juice, and, as is the case for most domesticated plants, they would have required constant attention from man in order to give him satisfactory yields. The notion that viticulture and viniculture originated somewhere in the Near East, and was disseminated from there, is supported by the fact that there is a remarkable similarity in most Indo-European languages in the words for ‘vine’ and ‘wine’, indeed, Renfrew3 goes further and maintains that the spread of agriculture into Europe resulted from the dispersal of people speaking Proto-Indo-European languages. Conversely, there is little resemblance between the words for ‘grape’ in the same group of languages, and this is taken to signify that the appreciation of, and use of the grape occurred a long time before the advent of viticulture and viniculture, and the abovementioned dispersal of Indo-European languages into Europe. In contrast, Semitic languages, that evolved in regions where the vine was not indigenous, have often adopted words for ‘vine’ and ‘grape’, which are very similar to those for ‘wine’, and are thought to be related to woi-no, an ancestral term for wine. According to some authorities, this lexical similarity implies that knowledge relating to grapes, viticulture and viniculture was obtained concurrently. If the above Noah hypothesis is correct, then it is possible that from Transcaucasia the vine (and wine) became transplanted into the Indian sub-continent, and then back to the Mediterranean basin. Support for such a notion comes from the fact that, in Sanskrit, the oldest of the Indo-European family of languages, ‘vena’ translates as ‘favourite’.

1.2 DISSEMINATION OF VITICULTURE

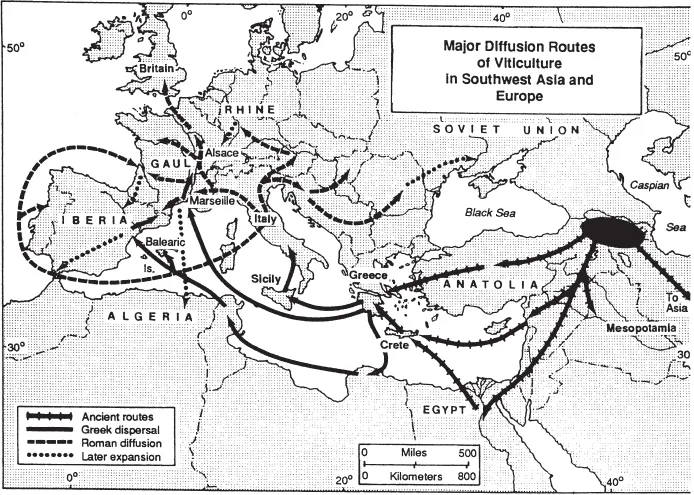

In simple terms, it is still commonly believed that domesticated vines were carried westwards by humans, along with the shift of agriculture generally, into the Mediterranean Basin, and from thence into different parts of Europe by Greeks and Roman colonists. The Greeks are credited with the transport of cultivated vines into Italy, and the Romans took them to Spain, France and Germany. It should be stressed, however, that movements such as these are not as certain as parts of the historical record might suggest, for changes in V. vinifera seed and pollen morphology indicate that domestication was occurring in some parts of Europe before the agricultural revolution supposedly reached that continent! Work by Stevenson,4 for example, has indicated that an extensive system of viticulture was already in existence in southern Spain several centuries before colonisation by the Phoenicians. Until many wild grapevine populations were annihilated by ‘foreign’ pests and diseases in the mid-19th century, the subspecies sylvestris remained abundant throughout its natural range, from Spain to Turkmenistan. Large populations of wild vines still exist in certain regions within their indigenous range, such as south-western Russia, where they were afforded protection from the abovementioned scourges, and have been used for winemaking over several millennia. It is thought that these locally occurring and adapted vines might be the progenitors of most of today’s European cultivars, and it is notable that the Pinot group of cultivars, for instance, possesses many traits resembling V. vinifera subsp. sylvestris.

From whatever its exact place of origin, the domesticated vine seems to have diffused in two directions. One route was to Assyria, and thence to the Mesopotamian city states of Kish and Ur, and, in later times, Babylon, where wine, because of its rarity, was mostly regarded as a drink for the upper classes, and the priesthood. The hot, dry climate, and soil salinity in Mesopotamia were not conducive to growing vines, and so most of the wine consumed by the civilisations there was imported from further north, from Assyria, for example, where there was higher rainfall. From Mesopotamia, under the influence of man, wine and the vine reached the Jordan Valley, somewhere around 4000 BC. The vine never grew in this part of the world, and from there it reached ancient Egypt, where, again, the grapevine is certainly not indigenous, but where there were certain areas favourable for the growth of Vitis. Vines became established in the Nile Delta by 3000 BC., at the beginning of the Early Dynastic period, and, by the New Kingdom times a very sophisticated form of viticulture was being practised. Viticulture followed the Nile upstream into Nubia, where it flourished until the advent of Islam. By 1000 BC wine drinking was widespread over much of the Near East, and was practised by, among many others, the Hebrews, the Canaanites, and the closely related Phoenicians, even if it was largely restricted to the higher strata in society.

The second route carried wine across Anatolia to the Aegean, where, by 2200 BC, it was being enjoyed by the Minoan civilisation on Crete, and in Mycenaea, where viticulture and viniculture became highly specialised, and wine was an important commercial commodity. Of great significance is the fact that wine (and vines) became an integral part of Greek culture, and, wherever they established a colony around the Mediterranean, wine drinking, viticulture and viniculture were sure to follow. Indeed, Sicily and southern Italy became very important vine-growing areas to the Greeks. Another important site was Massilia (now Marseilles), from where the Greek methods of viticulture and viniculture spread inland, following the valley of the River Rhône. The suggested major diffusion routes of viticulture in southwest Asia and Europe are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Likely diffusion routes of viticulture in southwest Asia and Europe (after de Blij5)

(Reproduced by kind permission of Professor H.J. de Blij)

1.3 THE EARLIEST CHEMICAL EVIDENCE FOR ANCIENT WINE

In 1996, McGovern et al.6 reported on the re-investigation of some residues found on the inner surfaces of pottery sherds, the analysis of which showed, beyond doubt, that the original jars had contained wine. The sherds had been recovered in 1968 from Hajji Firuz Tepe, a Neolithic site south-west of Lake Urmia, in the northern Zagros Mountains. The site is on the eastern fringes of the ‘Fertile Crescent’. Wild Vitis still grows in this region, and pollen cores taken from the deposits of Lake Urmia showed that it grew there during Neolithic times. The site was excavated as part of the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s Hasanlu project. The jars had been found embedded in the earthen floor of the kitchen of a mud-brick building dated to ca. 5400–5000 BC. During the original excavations, a yellow residue was noted on the inside lower half of a jar fragment. At the time, the deposit was assumed to be from some sort of dairy product, even though chemical analysis yielded no positive results. After a gap of 25 years, some sherds (one with a reddish residue) were re-examined using more sophisticated methods. Results showed that the deposits contained tartaric acid, calcium tartrate and the oleoresin of the terebinth tree (Pistacia atlantica Desf.). Tartaric acid occurs naturally in large amounts only in grapes, and was converted into its insoluble calcium salt in the calcareous environment of the site. P. atlantica grows abundantly throughout the Near East, and was widely used as a medicine and a wine preservative in antiquity. Judging by their long, narrow necks, the fact that the residues were confined to their bottom halves, and the presence of clay stoppers of approximately the same diameter as the necks, it was evident that these jars once contained some sort of liquid, and had been sealed. All the evidence supported the conclusion that the Hajji Firuz jars originally contained resinated wine, the like of which has been found in other, more recent contexts in the ancient Near East and ancient Egypt. If all the six jars found contained wine, then it was estimated that there would have been around 14 gallons in all, quite a significant production for household use. As McGovern commented,7 ‘If the same pattern of usage were established across the whole of the site’s Neolithic stratum, only part of which was excavated, one might conclude that the grapevine had already come into cultivation.’ He also tentatively asked the question (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) whether the difference in colour (yellow and red) of some of the deposits might have represented early attempts at making white and red wine.

The first published chemical evidence for ancient Near Eastern wine8 emanated from excavations carried out on the Period V site at the Late Chalcolithic village of Godin Tepe, in the Kangavar Valley in west-central Iran, during the years 1967–1973. The site is located high in the Zagros Mountains, and Period V dates from 3500 to 2900 BC, which is contemporary with the Late Uruk period (as the Late Chalcolithic in lowland Greater Mesopotamia is known) in southern Mesopotamia, and sits alongside the ‘High Road’, or the ‘Great Khorasan Road’, which later on became part of the famous ‘Silk Road’, leading from Lower Mesopotamia to Iran. Godin Tepe controlled the most important east–west route through the Zagros Mountains between Baghdad and Hamadan, and may have been a Sumerian or Elamite trading post. Certainly, Godin Tepe was well positioned to participate in trade, and, especially, to protect the trade route, being situated, as it was, some 2 km above the alluvial lowlands. It was adjacent to the eastern edge of Lower Mesopotamia, where some of the world’s earliest literate cultures had formed themselves into city-states, such as Lagash, Ur, Uruk and Kish. In addition, the Elamite capital of Susa (modern Shush, in Iran) was some 300 km to the south, and the proto-Elamites at this time were already well on their way towards developing an urban way of life. The city-states in the Tigris–Euphrates valley were based on the irrigation culture of cereals, dates, figs and other plants.

From the evidence given by imported items, these adjacent lowland cultures appear to have been in contact with several other parts of the Near East, such as Anatolia, Egypt and Transcaucasia. There was much evidence of an import trade in precious commodities, such as gold, copper and lapis lazuli, and even in everyday requirements, such as wood and stone, which were not readily available in the lowlands. Many resources, essential to urban lowland life, were available in the Zagros Mountains, and so Godin Tepe was ideally placed to take account of, and assimilate developments occurring elsewhere in the world.

In 1988, some years after the original excavations at Godin Tepe had been completed, a reddish residue found on some pottery sherds from unusually shaped jars, was re-examined, using infrared (IR) spectroscopy. The spectra obtained clearly showed the predominant presence of tartaric acid, and its salts, principal components of grapes, and it was presumed that the jars had once contained wine, which had evaporated and left a residue. The wine jars proved to be of a type not found elsewhere, or, at least, imported from a region not explored archaeologically (or not reported). The jars, which had been stored on their sides, and had been stoppered, were unique in several respects, all of which were consistent with them being used to store liquid. Firstly, a rope design had been applied as two inverted ‘U’ shapes along opposite exterior sides of each vessel (termed rope-appliqué). The specific rope patt...