![]()

CHAPTER 1

Small Molecule Ligands for Bacterial Lectins: Letters of an Antiadhesive Glycopolymer Code

THISBE K. LINDHORST*a

aOtto Diels Institute of Organic Chemistry, Christiana Albertina University of Kiel, Otto-Hahn-Platz 3–4, 24118 Kiel, Germany

1.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses how glycopolymers might function in the context of microbial adhesion. This is an important topic as attachment of viruses and bacteria to surfaces is a global problem and for host organisms it has fundamental implications for their vitality. This was considered when the human microbiome project was launched in 2008. Consequently, the human microbiome project is dedicated to research into how changes of microbial colonization influence human health and disease.1

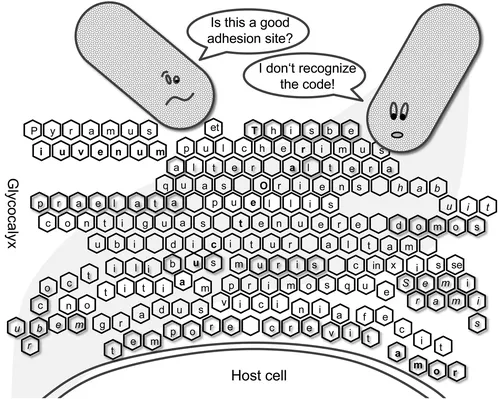

It has turned out that microbial colonization of the body is largely associated with the glycoconjugate decoration of the host cells, named the ‘glycocalyx.’ The glycocalyx of a cell is an extracellular compartment comprising a huge variety of different glycoconjugates. Strikingly, it forms an anchoring platform for invading microbes. It has been asked how carbohydrate recognition has evolved among microbes,2 how it is regulated and how it develops during the lifetime of an organism, in other words, how binding to cell surface carbohydrates is being ‘spelled’ (Figure 1.1). It has been suggested that the oligo- and polysaccharide structures that are expressed on cell surfaces function in the sense of a ‘glycocode,’3 thus paralleling the biology of carbohydrates with the alphabet of a language, in order to decipher its meaning.4 Of course, it is sensible to consider the diversity of carbohydrate structures as a biologically meaningful concert corresponding to the whole of molecular interactions. Glycopolymers can be regarded as a means to interrogate a putative carbohydrate alphabet and, moreover, as a powerful tool to prevent microbial colonization of surfaces.

Figure 1.1 ‘Deciphering the glycocode.’4 Cartoon to exemplify that carbohydrate-specific adhesion of, e.g., a bacterial cell to the glycocalyx of a host cell might be looked at as reading a code.

1.2 Lectin-Mediated Bacterial Adhesion

To colonize cell surfaces of the host, bacteria, for example, have to accomplish a process of adhesion in order to withstand natural defence mechanisms and mechanical shear stress. Stable adhesion can lead to the formation of bacterial biofilms, which is accompanied by vital advantages for the microbial colonies5 but disadvantages for the host. Finally, adhesion apparently is a prerequisite for bacterial infections that constitute a major global health problem, in particular in developing countries. Bacterial infections are especially dangerous for newborns and young children,6 with the most common serious neonatal infections involving bacteremia, meningitis and respiratory tract infections. Key pathogens in these infections are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.7

One important mechanism of bacterial adhesion is based on molecular interactions between cell surface carbohydrates of the host and specialized carbohydrate-specific bacterial proteins called adhesins or lectins. Lectins were first described at the end of the 19th century,8 when it was shown that plant lectins have the ability to agglutinate erythrocytes blood group specifically. As we know today, this is a result of a multivalent carbohydrate–lectin interaction. In 1954, Boyd and Shapleigh proposed the term lectin ‘for these and other antibody-like substances’ with blood group-specific agglutination properties.9 In the 1990s, Lis and Sharon10 suggested that ‘lectin’ should be used as a general name for all proteins of non-immune origin that possess the ability to agglutinate erythrocytes and other cell types. Early classification of lectins relied on their carbohydrate specificity. However, today lectins are grouped on the basis of their structural features and especially the relatedness of their carbohydrate binding sites, which are often called ‘carbohydrate recognition domains,’ or CRDs.11–13

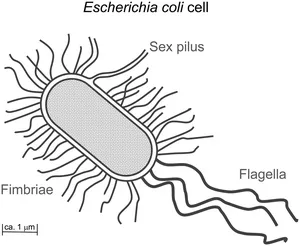

It is common knowledge today that lectins are ubiquitously spread in Nature, comprising many different functions in different organisms.14 Also, many bacteria, in particular those of the Enterobacteriaceae family, have the ability to agglutinate erythrocytes by their own lectins. This haemagglutination activity of bacteria is almost always associated with the presence of multiple filamentous protein appendages projecting from the surface of the bacteria.15 These are called fimbriae (from the Latin word for ‘thread’) and also, less correctly, pili (from the Latin word for ‘hair’) (Figure 1.2). Whereas pili are involved in gene transfer between bacteria (‘sex pili’) and flagellae have the role of sensory organelles used for moving, fimbriae serve as adhesive organelles. Fimbriae contain lectin subunits, which mediate carbohydrate-specific adhesion to cell surfaces (and also cell agglutination). Thus, bacteria utilize the sugar decoration of cells – the glycocalyx – to colonize the cell surface, wherever cells are in contact with the outside environment, as for example in the case of epithelial cells.

Figure 1.2 A majority of bacterial cells, such as E. coli, are equipped with three types of hair-like protein appendages, named pili, fimbriae and flagella. Fimbriae serve as adhesive organelles, mediating adhesion to the glycocalyx of host cells. E. coli cells are covered with several hundred copies of fimbriae of different carbohydrate specificity.

1.3 Carbohydrate Specificity of Type 1 Fimbriae

Type 1 fimbriae are particularly efficient adhesion tools of bacteria to mediate the colonization of various biotic and abiotic surfaces. They are uniformly distributed on the bacterial cell surface with their length varying between 0.1 and 2 µm and a width of ∼7 nm. Since the 1970s, numerous studies have been carried out to elucidate the carbohydrate specificities of bacterial adhesion, in particular of type 1 fimbriae-mediated adhesion of E. coli.6 A key finding of this research was that the type 1 fimbrial lectin, called FimH, requires α-D-mannose and α-D-mannosides for binding. The other anomer, namely β-mannosides, cannot be complexed within the carbohydrate binding site. This knowledge suggested that type 1 fimbriated bacteria can adhere to tissues expressing glycoproteins of the high-mannose type, exposing multiple terminal α-D-mannosyl units.16 For example, urinary tract infections are caused by uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC). Type 1 fimbriae are present in at least 90% of all known UPEC strains, where they are important pathogenicity factors.6,15 Today, it is known that bacterial adhesion to the surface of urothelial cells is mediated by FimH binding to oligomannoside residues of the glycoprotein uroplakin Ia. This interaction is a prerequisite for bacterial invasion.17 Consequently, much effort has been invested in the development of potent inhibitors of type 1 fimbriae-mediated bacterial adhesion in order to prevent bacterial adhesion to mucosa and thus treat bacterial infection in an approach that has been called antiadhesion therapy.18,19

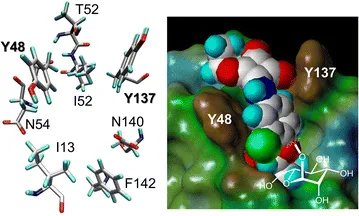

In this context, a second feature of type 1 fimbriae-mediated bacterial adhesion that was discovered already quite early is important.16 It was found that α-D-mannosides with an aromatic aglycone moiety exhibit an improved affinity to the bacterial lectin and an enhanced potency as inhibitors of type 1 fimbriae-mediated bacterial adhesion to surfaces. Today, this finding is well understood based on the X-ray studies of the structure of the type 1 fimbrial lectin FimH that have been published since 1999.20–23 Structural biology has shown that the entrance of the carbohydrate binding site of FimH is flanked by two tyrosine residues, Y48 and Y137, which make π–π interactions with an aromatic aglycone of an α-D-mannoside ligand that is complexed within the cavity of the FimH carbohydrate binding site (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Left: spatial orientation of the amino acid residues at the entrance of the carbohydrate binding site of the bacterial lectin FimH as revealed ...