aShanghai Key Laboratory of Chemical Biology and State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering, School of Pharmacy, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, China;

bShanghai Key Laboratory of New Drug Design, School of Pharmacy, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, China;

cLaboratory of Biocatalysis and Synthetic Biotechnology, State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, China;

dCell Free Bioinnovations Inc., 2200 Kraft Drive, Suite 1200B, Blacksburg, VA 24060, USA;

eSchool of Biotechnology, State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, China;

fBiofuels Institute, School of the Environment, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang 212013, Jiangsu Province, China

*E-mail:

[email protected] 1.1 The History and Applications of Biotechnology

The term ‘biotechnology’ first appeared in Manchester University, England, early in the 20th century.1 In 1912, C. Weizmann isolated a strain of Clostridium acetobutylicum that converted carbohydrate into butanol, acetone, and ethanol.2 In 1923, T. Walker commenced undergraduate education in the department of fermentation industries; the name of this department was then changed to industrial biochemistry, similar to ‘biotechnology’.1 K. Ereky, a Hungarian engineer and the founding father of biotechnology,3 first coined the word “biotechnology” in a book published in Berlin in 1919 called Biotechnologie der Fleisch-, Fett- und Milcherzeugung im landwirtschaftlichen Grossbetriebe (Biotechnology of Meat, Fat and Milk Production in an Agricultural Large-Scale Farm), in which he explained a bioprocess technology that converts raw materials into a more valuable product. He further developed this concept for the 20th century: Biotechnology means solutions to many social and natural crises, such as food and energy shortages.2

In fact, biotechnology as a methodology has existed for a long time, although the term “biotechnology” did not exist then. Around 8000 BC yeast was used to make wheat wine by the Chinese, and also around 6000 BC by the Sumerians and Babylonians.4 Around 4000 BC the Egyptians used yeast to bake leavened bread. The ancient Chinese produced copious amounts of liquor, rice wine, soy sauce, and vinegar with the earliest biotechnology utilizing conversion by some microbes.5

In AD 1673 A. v. Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch scientist known as “the father of microbiology”, pointed out the functions of microorganisms in fermentation6 and made contributions towards handcrafted microscopes and the establishment of microbiology. He was the first one to observe and describe single-celled organisms as animalcules, which are now referred to as microorganisms.

Vaccines, which protect people from some terrible diseases, are a typical biotechnology.7 In the 16th century, the Chinese inoculated smallpox scab powder on the body to protect from smallpox infection. E. Jenner (1749–1823), an English physician known as “the father of immunology”, heard a dairymaid’s story and started to study cowpox vaccine. L. Pasteur (1822–1895), the other founder of medical microbiology, was famous for his creation of two vaccines for rabies and anthrax.

A. Fleming (1881–1955), a Scottish scientist, discovered the antibiotic penicillin, a secondary metabolite from Penicillium fungi, in 1928,8 the most famous example of a biopharmaceutical from biotechnology. Now, the majority of penicillin employed worldwide is produced by this kind of method in China.

Today’s biotechnology in the form of genetic engineering was established by G. Mendel (1822–1884), an Austrian scientist and the father of modern genetics.9 W. Sutton (1877–1916), an American scientist, applied the Mendelian laws of inheritance to the cellular level of living organisms and established chromosome theory.10 The structure of DNA was discovered by J. Watson (born April 6, 1928), an American scientist, with F. Crick (1916–2004), an English scientist, in 1953. This discovery resulted in an explosion of research in molecular biology and genetics, opening the door for the biotechnology revolution.11

P. Berg (born June 30, 1926), an American scientist awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, obtained the first recombinant DNA molecule and established the foundation for modern biotechnology.12

1.2 Introduction to Chemical Biotechnology and Bioengineering

1.2.1 Chemical Biotechnology and Bioengineering

Biochemistry is a traditional discipline focused on the knowledge and principles of the behavior of natural and endogenous chemicals or substances in life and biological systems. However, chemical biology is a young scientific discipline spanning chemistry, biology, and physics; it mainly uses chemistry, i.e. exogenous (or exogenously added) chemicals as a perturbation methodology to reveal biological laws or solve biological problems. It involves the application of chemical techniques, tools, and analyses, and chemicals from nature or produced through synthetic chemistry, for the study and manipulation of biological systems.

Science is the foundation of technology and engineering. Technology and engineering are the derivation and application of science, which really solve the practical problems related with social and natural crises. Accordingly, chemistry has chemical technology and engineering as its partner, and biochemistry has biochemical technology and engineering as its partner, so chemical biology should have its own partner—chemical biotechnology and bioengineering!

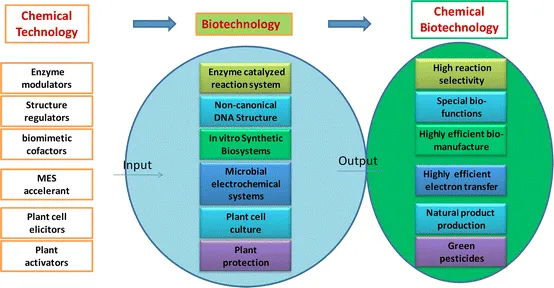

However, new methodology is needed to solve many practical problems. We know that biochemical technology or engineering can be defined as using biological methodologies and substances to solve practical and chemical problems in the areas of industry, medicine, and agriculture. Therefore, chemical biotechnology or bioengineering can be defined as using chemical methodologies and substances to solve practical and biological problems. Although one or two publications have used “chemical biotechnology or bioengineering” to describe some processes in the former case for solving chemical problems in the chemical industry, in fact these are still biochemical technology or engineering, not real chemical biotechnology or bioengineering for the processes in the latter case.

If some exogenous (or exogenously added) chemical compounds are able to regulate (enhance or attenuate) a bioprocess for some desired objectives, we believe that the whole process belongs to the area of “chemical biology” or “chemical biotechnology”. However, there are some differences between chemical biology and chemical biotechnology or bioengineering. The former focuses on the theory, mechanisms, and activities in the laboratory, and the latter focuses on the operation value in the laboratory and applications in practice even beyond the laboratory.

Today, there is a distinct definition: Biotechnologies are processes that seek to transform biological materials of animal, vegetable, microbial, or viral origin into products of commercial, economic, social, and/or hygienic utility and value, and bioengineering focuses on their scale up methodology.

Therefore, the definition of chemical biotechnology and bioengineering is utilizing small chemical molecules to affect some specific bioprocesses in order to make this bioprocess perform better, or on a larger scale for improving our lives and the health of our planet, which could transfer some ecological biotechnologies more economically and make the relevant chemistry greener (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Illustration of chemical biotechnology and bioengineering.

In fact, for the latter these processes could be recognized as a type of green chemistry approach when used to solve chemical problems. For example, enzymatic reactions to achieve exquisite chemo-, regio-, and enantio-selectivities for pharmaceuticals with great sustainability in aqueous media and under mild conditions as described in Chapter 2, or multi-enzyme-based biotransformations to produce chiral compounds as drug precursors, sweet hydrogen, sugar biobatteries, and renewable chemicals under green conditions, as exemplified in Chapter 3.

1.2.2 Green Chemistry

Sustainability has become a central and focal issue for human beings today, even a political issue, but it previously did not attract much attention in human history. Strong disputes and conflicts as well as many stories at The World Climate Congress every year fully embody the world’s anxiety on this problem. With conflicts between development and the environment, it seems to be impossible to reach a harmonious balance between GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and GWP (Global Warming Potential). In this situation and stage, green chemistry is a new and acceptable solution or option that has been proposed to solve the balance between the economy and ecology.

Green chemistry embodies two main aspects. First, it emphasizes the efficient utilization of raw or natural materials and the concomitant elimination of waste. Second, it deals with the health, safety, and environmental issues associated with the manufacture, use, and disposal or re-use of chemicals.

Green chemistry as an important concept first appeared in the early 1990s, about 20 years ago. Since then, it has made great progress in many areas, including petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, household products, agriculture, aerospace, automobiles, cosmetics, electronics, and energy. There are hundreds and thousands of examples of successful applications of award winning, cost-effective, or economically competitive technologies. Many of them have played a significant role in informing sustainable design.13 Important early stories include the US Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards established in 1995 and the publication of the first volume of Green Chemistry, a journal from the Royal Society of Chemistry, in 1999.14

Green chemistry is a very important issue to scientists, engineers and society, and biotechnology is an efficient and attractive route to make chemicals and manufacturing processes cleaner or greener, efficiently and ecologically. However, from the economical view, most natural bioprocesses are still not robust enough for practical applications and industry; some chemical inducing agents, e.g. elicitors, modulators, and activators, are needed to promote or enhance the efficiencies of these biotechnologies, therefore, chemically promoted biotechnology and bioengineering make sense in this area.