![]() III

III

The Secondary Literature and Specialized Search Techniques![]()

CHAPTER 4

Searching Using Text: Beyond Web Search Engines

ANDREA TWISS-BROOKS

University of Chicago Library, 5730 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, US

Email:

[email protected]4.1 WHY WEB SEARCH ENGINES AREN’T ENOUGH

There is often a bewildering choice of sources for searching for topics in chemical information using text words. When looking for basic facts or for a specific article reference, Internet search engines (including Google Scholar) that search content on the open Web are often good tools. Freely available Web sites of chemical information, such as spectra, chemical properties, safety information, and more, abound. Using a Web search engine to perform chemically oriented topic searches using text terms can yield some good information, but this is usually not the best method of performing a more comprehensive topic search. When doing a more comprehensive search on a topic, you will need to use specialized tools. Journal publisher Web sites; publisher-produced, subject-specific databases (most of which require that your organization has a paid subscription or that you pay-as-you-go to use); online dictionaries, handbooks and other reference works; institutional or disciplinary repositories of preprints or final author manuscripts;1 and online collections of e-books provide additional resources for researching a particular chemical topic. Which of these you choose to consult will depend on your particular topic, and a comprehensive search probably requires that you use multiple resources in order to ensure a thorough search.

Topic searches should be a normal part of your strategy for a comprehensive literature review. In-depth topic searches are best performed using one or more subject-oriented databases. The best known and most comprehensive subject database for chemistry is SciFinder, produced by Chemical Abstracts Service,2 but, depending on your particular research topic, you may need to perform a topic search in additional databases. Other well-known chemistry databases, such as Reaxys,3 focus more on chemical and physical property or reaction data and may be less useful for text-based topic searching. Other commonly encountered scientific and engineering subject databases that contain references to the chemical literature are Inspec,4 PubMed,5 GeoRef,6 Compendex,7 and Web of Science.8 Subjects covered in these databases include physics (Inspec), medicine (PubMed), and earth sciences (GeoRef), as well as related chemical topics such as chemical physics, toxicology and medicinal chemistry, and geochemistry and atmospheric chemistry. If you are interested in business and economic aspects of industrial chemicals, environmental issues related to chemicals, or other tangential areas you may also want to consider selecting a business database and investigating government publications or other types of resources. Coverage of the databases varies not only by subject area but also by types of literature covered, and you should take this into consideration when you are selecting a database to search. If you are having difficulty in selecting or identifying the most appropriate database for researching a particular topic in chemistry or a related subject, consider consulting a chemistry or science librarian or information professional for assistance. If no chemistry or science librarian is available, you can still take advantage of the expertise of librarians by consulting one or more of the numerous library guides for chemistry that may be found on the Web.9

One of the most important factors in doing effective topic searching is the critical analysis of your search results. When you do a search, you want to retrieve results that have relevance to your research question. Relevance is defined in this context as “the ability (as of an information retrieval system) to retrieve material that satisfies the needs of the user”.10 Each researcher typically wants to find all the relevant results for his or her topic. However, when you want to retrieve the maximum number of relevant results, you may need to increase the recall of your search, which inevitably leads to retrieval of less relevant results (sometimes known as “false drops”) and, therefore, a reduction in the precision of the search.11 In cases where a very comprehensive search is required, you will need to individually review each retrieved reference to identify and eliminate the non-relevant results. Before starting your topic search, you need to have a general sense of the scope and magnitude of your expected search results. Is your topic part of a large research area where there has been extensive research publication? Is your topic in a new or emerging area of study where you do not expect very many publications? The judgment of how comprehensive a search needs to be also depends in large part on the consequences of missing a relevant citation; the cost of repeating a single experiment in the lab because of missing an article may be much lower than that of missing a critical reference for a patent application. One of the most difficult times to know when you have done a good search is when you have few or no results. It may mean that you have identified a fruitful area for new research, or it may just mean that you have not done a good topic search.

Using all the tools at your disposal includes examining the information available as a result of your initial searching efforts. If you have full text of a particularly pertinent journal article reference available, you can always go to the original research report. However, if you are not affiliated with a library that holds an institutional subscription and do not have your own personal subscription to a specific journal title, you may still have access to a considerable amount of information about the article or report. While the initial results of your topic search may be displayed using a short view that often includes the bibliographic information (author, article title, journal title, volume, date, pages, etc.), most databases will have at least one viewing option that provides additional information about the publication. These may include an author-provided or other abstract, additional subject terms or keywords that describe the content of the article, and a list of references used by the author in the footnotes or list of works cited. Even if the database you are searching does not include this additional information, many journal publishers provide access to abstracts and references on their publishing Web sites and do not require a subscription or other payment to access this additional information. They generally also offer the option to purchase access to the article, but it is important to check with your library or information center to see what document delivery options exist within your organization before paying to view a paper.

4.2 PRACTICAL APPROACHES TO SEARCHING A TOPIC USING SUBJECT DATABASES

When doing topic searching, it is important to understand the underlying concepts behind the construction of each database system or search engine. How your results are retrieved and presented may depend on a behind-the-scenes ranking algorithm, an underlying subject thesaurus, term mapping functionality that suggests synonyms to use, and the handling of term variants (different spellings, endings, and other variations). Each of these concepts will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

In addition to understanding how databases and other tools are constructed and what tools may be available to help construct a topic search in each database, it is also important to understand that chemical topic searching differs from other types of topic searching. Terminology is highly technical and often includes non-alphanumeric characters such as symbols, sub- and super-scripts, Greek letters, and punctuation, which may need to be entered in specific ways when constructing a topic search. Even the most modern search interfaces still rely on indexing done decades earlier, at a time when representation of Greek letters, mathematical symbols, and other special characters were not well handled by computer search systems. Since each database interface treats these special characters differently, you should consult the online help feature of the individual database for assistance, or seek advice from your librarian or a more experienced user.

4.2.1 Controlled Text Terms

Topic terms appear in the title, author- or publisher-written abstract, full text of the article, author-supplied keywords, and additional subject or indexing terms. Most subject databases provide these additional indexing terms that are applied by automated algorithms, by human indexers, or both. These additional indexing terms are usually selected from an official list of terms maintained by the database or index producer and are sometimes referred to as controlled vocabulary. In order to perform a comprehensive subject search or to improve the precision of your search, consider using the database’s controlled vocabulary, but recognize that use of controlled vocabulary terms does have some limitations. New or emerging areas of research will not be well covered by controlled vocabulary terms since it takes some time for new terms to be adopted into a controlled vocabulary. Records for very recently published journal articles may be included in the databases as provisional or preliminary records before controlled indexing terms have been applied.

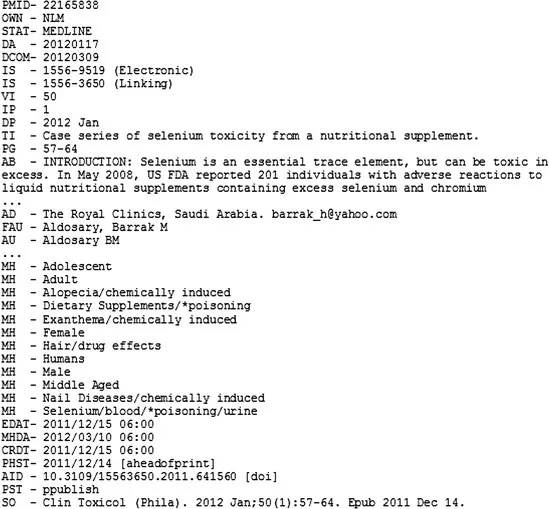

When controlled vocabulary is available, the records in the subject database usually display the terms in separate fields. Each individual field or element of the record (accession number, dates of various kinds, journal title, page numbers, abstract, etc.) usually starts on a separate line and is preceded by a tag or code representing the name of the element or field. An example of a fielded record12 from the PubMed database appears in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Example of a database record from PubMed containing controlled vocabulary terms (Note: portions of the record were omitted for clarity and are indicated by ellipses).

Controlled vocabulary terms in Figure 4.1. are preceded by “MH”, which stands for Medical Subject Heading, or MeSH. The MeSH vocabulary is a highly developed hierarchical system of controlled terms created by the N...