eBook - ePub

Histological Techniques

An Introduction for Beginners in Toxicology

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Histological Techniques

An Introduction for Beginners in Toxicology

About this book

Histological techniques form the basis of many areas of research, yet they can often be poorly understood. Aimed at postgraduate students and those at an early stage of their career, this title provides a detailed and comprehensive introduction to histological techniques. With detailed images and slides, this book provides a unique overview of the area while providing the reader with a guide to how to use and incorporate histological techniques within their own research. Written by experts working within the field, this book is an essential handbook for anyone wanting to learn more about histological methods and how to apply them successfully.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Histological Techniques by Robert Maynard, Noel Downes, Brenda Finney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pathology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Histology is the science of cells and tissues and plays an essential part in toxicological investigations. Though histological work is often limited to specialists in the subject there is no reason why this should be so: the application of basic histological methods is within the reach of any research worker in the biological sciences. Routine histopathology can be a quick and cheap way to answer simple questions. Many questions are initially relatively straightforward and histopathology is very good at guiding the researcher towards the specifics where more in depth investigations can be better targeted.

Planning research is all about asking questions and devising means for answering them. In this chapter the reader is introduced to the sort of problems which are amenable to histological approaches. Histology is often regarded as a descriptive discipline and so, to a large extent, it is. But histology can be used to test hypotheses and thus can make a great contribution to the advance of biological research. Linking histological techniques with how to think about histological problems is the aim of this introductory chapter.

1.1 Histology for Toxicologists

This chapter sets out the background to histological studies in toxicology and takes the reader into a few imaginary studies. These provide a fore-taste of subsequent chapters and allow the beginner to see what an interesting and scientific subject histology actually is.

The study of toxicology includes the study of damage to cells and tissues produced by chemicals. Such damage may be studied in a variety of ways; for example, damage to the lung or liver may be studied by tests of the functional capacities of these organs. Lung function tests and liver function tests provide physiological and biochemical information about how well these organs are working. Damage may also be studied by histological methods: tissues are examined for signs of damage. In some cases evidence of structural damage can be related to evidence of impairment of function. Evidence of structural damage also provides clues as to the mechanisms of the effect of chemicals. Some chemicals produce very specific forms of tissue damage and these have been described in detail. Textbooks of toxicology contain detailed descriptions of, for example, the effects of compounds such as chloroform or carbon tetrachloride on the liver.

A search for evidence of structural damage is an essential part of the study of the potential toxicological effects of any new chemical. Standard approaches have been developed and production-line methods are applied to sampling of tissues, processing of tissues for histological examination and to the examination itself of the histological sections produced. These production-line methods allow the screening of a wide range of tissues and are carried out to Good Laboratory Practice standards. Such standards ensure that the results of the studies are reliable.

Histological techniques are also applied, but in a less standardised way, during research into the effects of chemicals. For example, one might be studying the efficacy of a skin decontaminant and become concerned about the possible toxicological effects of the compound on the skin. It would be entirely reasonable, indeed necessary, to examine samples of skin histologically in an attempt to find evidence of damage. Similarly, if one were studying the effects of nano-particles on the lung one would wish to look closely at the lungs of animals killed at intervals after exposure to the material under study. Such work is a little different from the production-line approach taken in the screening of chemicals for possible toxicological effects. It tends to be done on a smaller scale and, perhaps, sometimes by less experienced workers. Of course such work should be performed to high standards and in accordance with the guidance of Good Laboratory Practice and Health and Safety standards. But varying and extending the approach as new ideas occur is the essence of research and producing a definitive plan of the methods to be used before any methods have been deployed is often impossible. For example, one might begin by examining paraffin sections of kidney and then decide that frozen sections that allowed the histochemical study of specific enzymes were needed. This “following the clues as they appear” approach is essential in research work. However, there are dangers in such an approach. One might be led to inappropriate methods or one might be led to difficult methods of which one has little experience and which require great skill before the results can be accepted as reliable. The “try ‘em all” approach is ever-appealing and needs to be resisted.

Workers with limited experience of histological methods are often tempted to “have a look” at the tissue just in case anything odd or interesting can be seen. In an ideal world such work would be undertaken by an experienced histopathologist. This, however, is far from an ideal world and histopathologists are neither many nor under-employed. Thus, the toxicologist might feel he or she should “do some histology” as a part of their research project. Such an aspiration should be encouraged: much can be learnt from histological studies. But, of course, badly performed histological studies, like all badly performed studies, may be worse than useless in that they can be misleading. Poor tissue preparation may lead to incorrect appreciations of effects, or effects might be missed. Additionally, the wide range of artefactual changes that appear in badly prepared material may mislead the observer. The results of such studies may be disappointing and the researcher might be discouraged.

Toxicologists usually receive some training in histology and histopathology. Post-graduate courses in toxicology (often leading to Masters’ degrees) usually include teaching on histopathology. But such courses cannot provide much practical experience and lessons learnt can be forgotten. Toxicologists with a predominantly biochemical or chemical background may lack familiarity with histology: this can hardly be regarded as their fault and they may have passed their training in histopathology with a sigh of relief and a resolution not to return to it. Toxicologists with a medical or veterinary background might be expected to be more enthusiastic about the study of histology and its derivative histopathology, though their experience of the practical aspects of the subjects may also be limited. The teaching of histology in medical schools has been squeezed over the last thirty years by the accretion of newer subjects to the curriculum. The traditional histologist might well complain that making drawings of sections has disappeared; he might despair that the examination of histological sections is fast following the practice of drawing! No medical students are now required to stain histological sections, let alone to cut sections. Are medical students required to examine histological sections with a microscope? In some medical schools this is not required and video presentations have taken the place of microscopy. Is this a bad thing? Most histologists would answer, yes. Nothing beats examining sections. Video presentations are better than relying only on an atlas with perhaps not more than a few photomicrographs of any one tissue, but they cannot replace the microscope in terms of showing the student the range of appearances of sectioned tissue. In addition, the resolution provided by a television screen may be poorer than that provided by a properly adjusted microscope. Veterinary students are better trained than medical students in the practical techniques of pathology, but in both professions it is accepted that histopathology is, in general, a post-graduate discipline.

1.2 So Who is this Book for?

This book is aimed at the beginner, the scientist, and perhaps the post-graduate student, who makes no pretence of yet being a histologist, but who would like to know something more about the subject and would like to use histological techniques in his or her research but is not sure which techniques might be useful. It is not aimed at the medical or veterinary histopathologist; indeed, such experts might well treat the advice provided in this book with appropriate disdain.

Emphasis has been placed on both the “WHY” and the “HOW” of histological techniques. Many books describing histological methods are available. Such books offer the beginner a vast, indeed bewildering, range of techniques and this may be off-putting or even confusing. Books explaining why specific methods might be used are fewer: textbooks of histochemistry, for example, explain in detail how specific enzymes might be studied but, surprisingly, provide little advice on why one might wish to undertake such studies in the first place. Diagnostic histochemistry is a little better served: those interested in diseases of the liver and, perhaps specifically, in the formation of bile, or in tumours that produce certain hormones, might expect useful histochemical methods to be described within accounts of these diseases.

What are the problems likely to be faced by our ideal reader? Much depends of the environment in which he or she works. If a large, well-staffed, helpful and not over-loaded histopathology service laboratory, staffed with expert technicians, is available to process our readers’ samples, and if expert histopathologists are accessible and willing to teach and discuss results, then our reader might feel that he or she is wasting time in trying to learn about histology by the “do it yourself” method. Nothing could be further from the truth. The better one’s understanding of the methods used, the better one’s understanding of the results produced and the reports provided by the experts. On the other hand, there might be little support available from experts and the scientist might need to prepare his own material and examine it him- or herself. Whilst this might be deprecated by experts, it is in fact by far the best approach. One need not strive to become an expert histopathologist with a wide knowledge of tissue reactions and an ability to detect and classify innumerable variants of rare tumours: what we are interested in is what happens in “our” tissue when it is exposed to “our” chemical. Thus, there is nothing to prevent someone who is not a trained histopathologist becoming a real expert on the effects of skin-decontaminant X on the sweat glands or melanocytes of the skin. Specialised expertise, acquired by practice, is difficult to beat. The personal satisfaction of knowing more about one’s own area than the universal expert is also far from negligible.

One of the greatest of histologists, Manfred Gabe, wrote in 1968:

“The young post-graduate embarking on a career of research has often been lulled for years on global attitudes. In nine cases out of ten he imagines that the primordial condition for success in scientific work is aptitude for philosophical generalization. Ready to juggle with fundamental ideas and edify grand hypotheses, our post-graduate would at the most deign to perform an experimentum crucis but would reject indignantly as a basely material task the very idea of having to handle a microtome, pipette or precision balance. Those of our future scientists who turn towards histology dream of sitting before an excellent microscope and examining preparations that have been made, cleaned and labelled by technicians to finally produce a theory of the structure of living matter.”

This is, perhaps, an exaggeration or perhaps not! Gabe’s book Histological Techniques ran to 1100 pages: the results of a survey to discover how many research workers using histological techniques are acquainted with the work would be interesting. If we judge by comparing Gabe’s trenchant criticism of “haematoxylin and eosin” (H&E) as a histological method with the universal adoption of this method, to the exclusion of nearly all others, then the number is likely to be low. The number, including the present author, who have not perused Gabe’s atlas of the histology of that elusive New Zealand reptile, the tuatara, must be very large.

1.3 What is Histology and What is Histopathology?

Histology is the scientific discipline that involves the study of the structure of normal cells, tissues and organs. The essential instrument is the microscope. Histopathology involves the study of the changes in cells, tissues and organs that occur as a result of disease processes or insults, for example, the effects of physical or chemical injury. Again, the microscope is the essential instrument. Of course, when “the microscope” is mentioned we imply all the variants of techniques that are included in the term “microscopy”, and thus we should consider light microscopy in all its many forms and electron microscopy, again in its many forms. The changes sought by histopathologists are changes that can be seen, but making the changes visible often requires the application of a range of techniques. At its simplest level, histological sections are prepared and examined. Their appearance is compared with that of normal tissue, either by reference to controls or to one’s memory of the normal appearance of the tissue being studied. Identifying visible changes is the first link in a chain of intellectual effort that includes deductions about the effects of the changes and about the mechanisms by which they have been produced. Further investigations may shed light on the mechanisms underlying the changes; these investigations may involve further examination of the tissue and the application of special techniques, including, for example, histochemical methods. But the process begins with observation.

In looking for changes one should remember that:

- We tend to see what we are looking for;

- The likelihood of our finding whatever it is we are looking for depends on our experience of looking for it and finding it.

Unfortunately, what we are looking for might not be seen because:

- It isn’t there, i.e., it does not exist;

- It has been destroyed during the processing of the material we are examining;

- It is not visible: a very different thing from not existing.

In addition, we might not recognise whatever it is we are looking for despite it being present. For example, imagine looking for an infiltrate of plasma cells into the connective tissue of the portal tracts of the liver. We should ask ourselves:

- Do we know what portal tracts are and do we know how to recognise them?

- Do we know what plasma cells are and do we know how to recognise them?

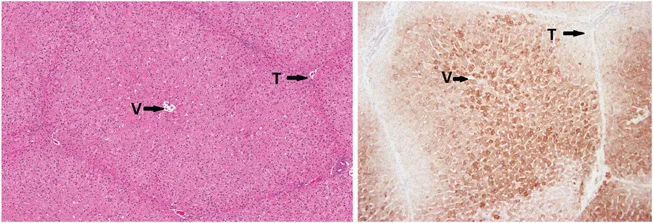

In both cases the application of special staining techniques will make our task easier. See, for example, Figure 1.1. Having found the portal tracts and having seen plasma cells, we should ask ourselves whether there are more of these cells present than we expected. Perhaps we should count them. We should certainly compare our material with control material in which the number of plasma cells present is assumed to be normal. To take another example: imagine that, whilst examining sections of liver stained with haematoxylin and eosin, you come across well-circumscribed areas that appear paler than the rest of the tissue. What does this mean? Is it an artefact of preparation or a real change that calls for interpretation? Comparison with control sections, or with memory of the normal appearance, will answer these questions.

Figure 1.1 Pig liver. Standard H&E on the left. Pig liver is particularly good for visualising the lobular pattern. Note the central vein (V) in the middle of the lobule and the portal triads (T) at the apices. H&E cannot, however, demonstrate function. The liver on the right is from the same animal, but this time stained with an immunohistochemical stain for cytochrome 3A4. As you can see, the activity, as demonstrated by the darker brown staining, is far greater closer to the central vein. (Image courtesy of Steve van Crutchen.)

Our problem is made a little more difficult by the presence of artefacts introduced during the processing of the tissue. We might see something that looks unusual, perhaps abnormal, and set about interpreting it. But perhaps the abnormality is not real in the sense that it was not present when the tissue was removed from the animal but has appeared since. Cynics sometimes refer to histology as “the interpretation of artefacts”. They are half right. Much of what we see is an artefact of processing, but experience tells us which artefacts, or appearances, are important and which are not. Close attention to detail is necessary: we might be looking for changes in the appearance and distribution of chromatin in the nucleus of a cell. Bad preparation might very easily cause changes to the normal appearance; the normal appearance, that is, after good preparation. In the days before the development of the electron microscope mitochondria wer...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 An Introduction to Histopathology

- Chapter 3 The Light Microscope

- Chapter 4 How to Examine Histological Sections

- Chapter 5 Tissue Processing: Fixation, Dehydration and Clearing

- Chapter 6 Paraffin Wax: Embedding and Section Cutting

- Chapter 7 Standard Staining Techniques

- Chapter 8 The Theoretical Basis of Histological Staining

- Chapter 9 Histochemistry

- Appendix

- Annotated Bibliography

- Subject Index