1.1 Introduction

The use of self-assembly processes to prepare nanoscale structures lies at the very heart of supramolecular chemistry.1 Indeed, through the use of self-assembly it is possible to prepare highly complex molecular architectures with targeted properties that can avoid lengthy, multi-step synthetic pathways. In the initial stages of research in the field of supramolecular chemistry the majority of studies were performed in the solution phase2 and more recently solid-state supramolecular chemistry has been developed combined with the wider field of crystal engineering.3 However, more recently the field of surface-based supramolecular chemistry has begun to be explored which has led to a significant interest in developing low-dimensional, predominantly two-dimensional, structures.4–10 The developments in this area are the focus of this chapter, including the synthetic approaches to such structures and the detailed characterisation of the resulting two-dimensional arrays that can be achieved using scanning probe microscopies.

Surface-based chemistry has long been utilised for assembling arrays of molecules. Perhaps the most widely studied area of such chemistry is the development of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of thiolate molecules adsorbed onto Au(111) substrates.11 The development of SAMs has been expansive and lies at the heart of many studies that attach molecules and, in some cases supramolecular arrays, to surfaces.12 Recent studies have demonstrated the use of supramolecular interactions between thiolate species to control the SAM formation.13 In the case of Au-thiolate SAMs and in many other instances deposition of molecules onto surfaces often leads to close-packed arrays that have well-defined arrangements; such arrays typically rely on van der Waals interactions and simple geometric preferences. However, the concepts of supramolecular chemistry open up the possibility of using stronger intermolecular interactions to create more complex and potentially porous structures. The logical extension of this approach is to use stronger interactions, ultimately leading to covalent coupling reactions to create robust low-dimensional arrays.

The emphasis of this chapter will be on studies where molecules are specifically designed in an attempt to control relative molecular organisation. In particular, the chapter will focus on the use of stronger supramolecular interactions, such as hydrogen-bonding, van der Waals interactions and lastly covalent coupling, to form extended arrays that propagate in two dimensions, parallel to the surface. Two-dimensional self-assembly of molecules on surfaces, when combined with scanning probe techniques, provides direct evidence of the potential of this approach. In some instances, examples show that such structures can be used to trap diffusing species as guests, in a similar fashion to porous architectures constructed in three-dimensional solids such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)14 and covalent-organic frameworks (COFs).15

The other main difference between solution-phase supramolecular chemistry and surface-based systems is of course the surface itself. Firstly, the surface defines a two-dimensional boundary upon which the self-assembly process is developed and secondly, the surface is far from innocent in the reaction process. Suitable surfaces often studied include Au(111),

16 [Ag(Si(111))]

17 and highly-oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG).

18 However recent studies have started to explore other substrates including graphene

19 and boron-nitride monolayers.

20 The choice of substrate is typically driven by their tendency to adopt weak interactions with organic molecules, which are commonly the focus of self-assembly studies. The surface organisation needs to be strongly influenced by intermolecular, supramolecular interactions, rather than surface effects to allow ready design of the resulting structure. Additionally, the requirements of specific scanning probe microscopies heavily influence the choice of substrate,

i.e. STM requires conducting surfaces for imaging, and this is in many instances the determining feature. Recent improvements in resolution of atomic force microscopy (AFM)

21 and the development of dynamic force microscopy (DFM)

22 have led to a wider scope for characterisation and therefore the choice of substrate is no longer restricted to (semi)conducting materials and insulating substrates are now realistic targets. Lastly, notably

in the case of covalently coupled structures, the choice of substrate is extremely important with the substrate often taking an active role in promoting coupling reactions.

The chapter is subdivided into four sections, systems assembled using (i) hydrogen bonds, (ii) van der Waals interactions, (iii) covalent bonds and lastly a section (iv) of self-assembled systems with unusual ordering that illustrate the power of the approach and particularly the molecular-level characterisation of such systems.

1.2 Two-dimensional Arrays Assembled Using Hydrogen-bonding

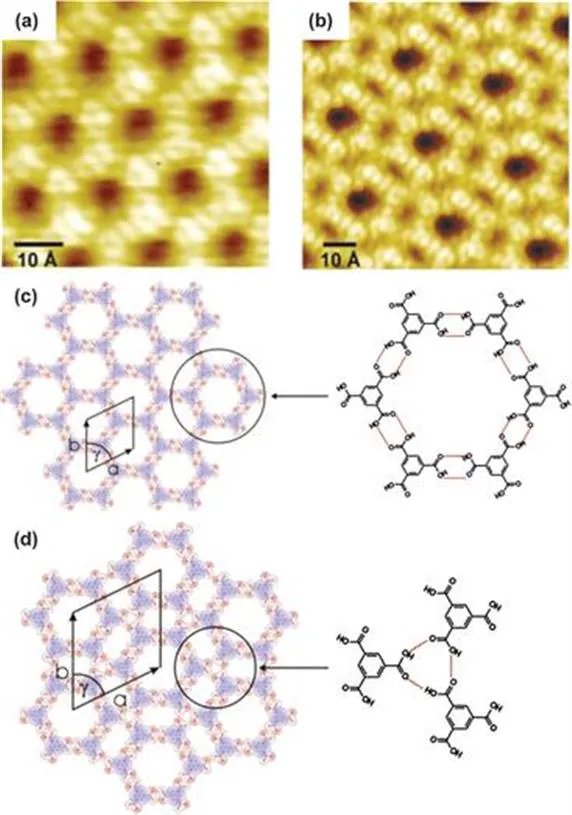

The use of hydrogen bonds to create supramolecular structures goes back to the origins of the field.23 Indeed it is relatively straightforward to use a simple molecule capable of self-recognition to create extended framework structures. Indeed, an early example of surface-based supramolecular chemistry—the formation of a unimolecular supramolecular structure mediated by hydrogen-bonding—was reported by Griessl et al.24 The structure was formed via deposition of trimesic acid onto a HOPG substrate in UHV conditions and imaging using STM (Figure 1.1a,b) reveals precise details of the self-assembled molecular structure. The carboxylic acid–carboxylic acid hydrogen bonds, which adopt the classic R22(8) intermolecular arrangement,25 ensure that an open structure is adopted in preference to a hypothetical, alternative close-packed arrangement, confirming that hydrogen-bonding interactions are the dominant force in producing these structures. The observed structure is the expected ‘chicken-wire’, or honeycomb arrangement leading to a porous network structure (Figure 1.1a,c). In addition to the honeycomb structure a secondary so-called ‘flower’ arrangement is also observed by STM measurements (Figure 1.1d). This alternative self-assembled structure results from the adoption of R33(12) supramolecular synthons formed by three carboxylic acid moieties from separate trimesic acid molecules. The ‘flower’ structure may form due to a higher molecular density on the surface, confirming that surface coverage also influences the final self-assembled structure by maximising the energy gained through adsorbate-substrate interactions.

Figure 1.1 Open network arrangements of trimesic acid on graphite under UHV at low temperature. (a), (c) The ‘chicken-wire’ structure; (b), (d) the ‘flower’ arrangement. Reproduced with permission from S. Griessl, M. Lackinger, M. Edelwirth, M. Hietschold and W. M. Heckl, Self-Assembled Two-Dimensional Molecular Host-Guest Architectures From Trimesic Acid, Single Mol., 2002, 3, 25. Copyright 2002 WILEY-VCH Verlag Berlin GmbH, Fed. Rep. of Germany.

A subsequent study of an elongated analogue of trimesic acid, 1,3,5-tris(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene, deposited on HOPG, but deposited from a range of alkyloic acids rather than by sublimation in UHV, also results in the formation of a honeycomb lattice at low temperatures, but a more densely packed phase at higher temperatures.26 The phase transition and the transition temperature between honeycomb and denser structures were found to depend on the nature of the solvent and molecular concentration. The authors suggested that the co-adsorption of solvent molecules within the honeycomb structure stabilises the nominally porous structure at low temperatures, but upon elevation of the temperature the weakly bound solvent molecules desorb initiating the transition to the more densely packed and thermodynamically-favoured phase.

A simple example of a unimolecular self-assembled structure that uses hydrogen bonds is that of naphthalene-1,4,5,8-tetracarboxylic diimide (NTCDI).27 NTCDI contains imide moieties at opposing ends of the rod-shaped molecule which can adopt imide–imide hydrogen bonds, again adopting an R22(8) intermolecular interaction, similar to that observed for carboxylic acid dimers. As a result of the divergent arrangement of the imide moieties linear chains are observed when the molecule is deposited onto a Ag/Si(111) surface (Figure 1.2a). Imaging using DFM of this molecule and the self-assembled array on a variety of surfaces28–30 reveals sub-molecular details of the molecular arrangement. It is interesting to note that features in the DFM images appear to coincide with where hydrogen bonds would be expected to be observed (Figure 1.2b), however calculations indicate that these features do not arise...